Early Life and Career

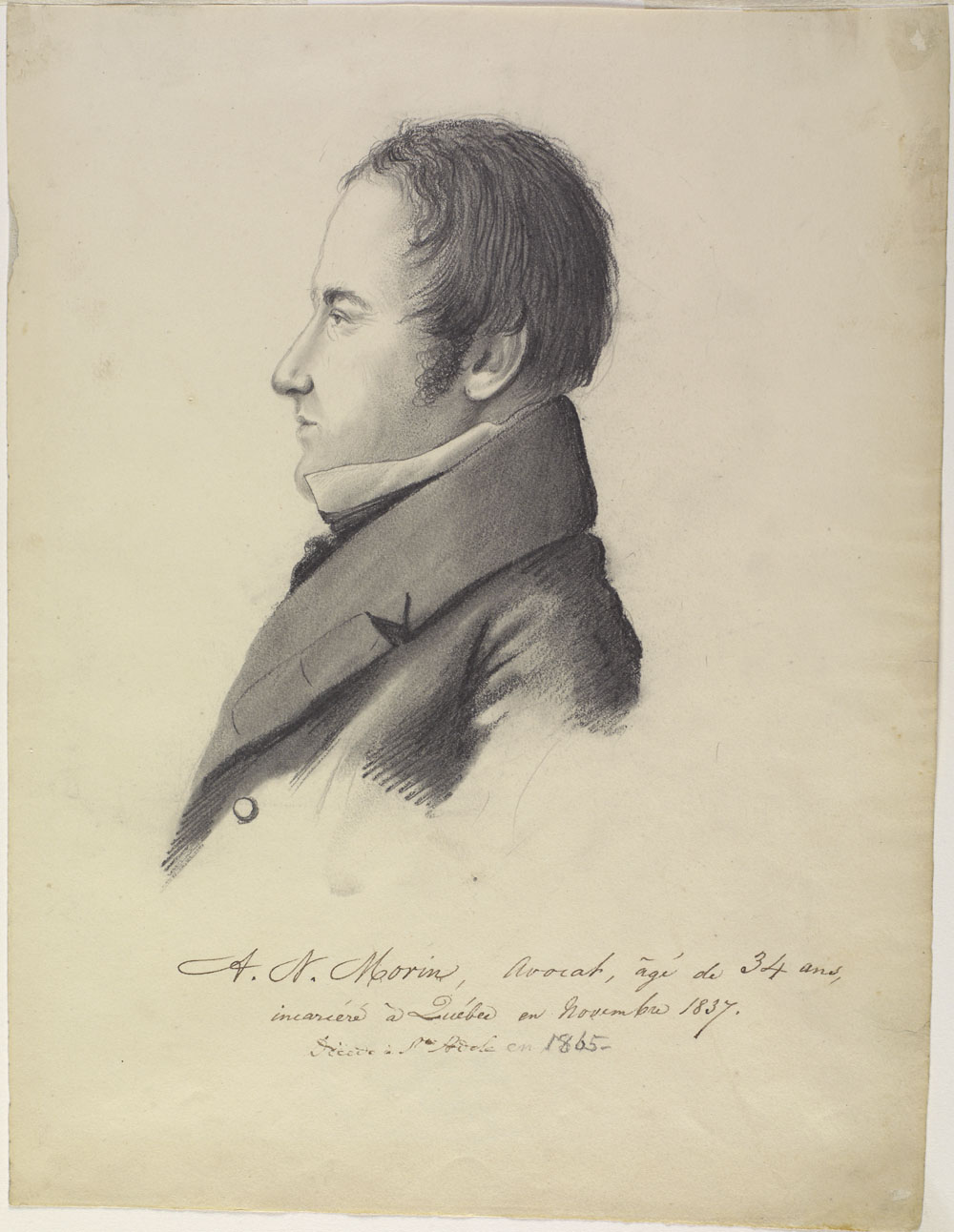

Born on 13 October 1803, Augustin-Norbert Morin had a difficult childhood. While he suffered from rheumatism, his family of farmers struggled financially and could not afford to send him to school. Thanks to Thomas Maguire, the parish priest for Saint-Michel, he received a formal education. Impressed by Morin’s intelligence, Maguire took him under his wing and in 1815 sent him to the Séminaire de Québec. Ultimately, young Morin opted to study law when he finished in 1822. Penniless and unable to continue his education, Morin began writing for Le Canadien. Morin then moved to Montréal, where he studied law under Denis-Benjamin Viger. Viger was not only a successful lawyer, but at that time was also one of most influential leaders of the Parti canadien.

Even at a young age, Morin was one of the colony’s leading nationalists. He had personal ties to important Patriotes, such as Viger, Louis-Joseph Papineau and Ludger Duvernay, and in 1825 he wrote a famous pamphlet critical of Judge Edward Bowen’s language policies. Bowen had refused to accept a writ of summons written in French. Signed “un étudiant en droit” (a student of law), Morin reminded Bowen that the use of French was a legal right in Lower Canada, protected by the terms of Conquest and the 1791 Constitution. At no point since Conquest, Morin argued, did Great Britain prohibit its use.

At the age of 23, Morin also founded La Minerve. However, one year later, in 1827, struggling to get his newspaper off the ground — it could only muster 240 subscribers — Morin sold it to Ludger Durvernay. Under Duvernay’s leadership, Morin’s newspaper became the mouthpiece of the Patriotemovement and one of the most influential newspapers in the colony. Morin did not leave the newspaper after selling it, but continued to act as editor until 1830. He also continued to produce articles for the newspaper after leaving this role.

The Patriote

In 1830, Augustin-Norbert Morin was elected to the Legislative Assembly by the electors of Bellechasse. Morin kept busy. A year into his mandate, for instance, he already sat on seven different committees. And after the difficult years of 1833–34 — during which he resigned from the Assembly due to “unsubstantial accusations of embezzlement” — he was set to become one of the most important Patriotes.

In 1834, Morin was a central figure in writing, at the request of the leader of the Parti patriote, Louis-Joseph Papineau, the 92 Resolutions, the iconic document listing all of the political reforms and demands sought by the Patriotes. In March of that same year, he was chosen by the Legislative Assembly to accompany Viger to London to present the document. Morin was also Papineau’s lieutenant in Québec City and in 1835, along with Viger, Edmond Baily O’Callaghan and Édouard-Raymond Fabre, among others, founded the Union patriotique de Montréal, an association that aimed to defend the colony and the Legislative Assembly from all unwarranted and unconstitutional interventions and abuse from colonial authorities.

Though Morin was initially one of the more moderate elements of the Patriote movement, he began to radicalize after 1836. According to historian Jean-Marc Paradis, Morin was “swept up in the whirlwind of events,” and actively participated in the 1837 Rebellion, leading the charge at Québec. His attempt to motivate the population of the city to revolt was, however, a complete failure. Historians like Paradis and Antoine Roy have stated that despite his commitment to the movement, he was not a natural-born leader. Following the 1837 Rebellion, Morin fled to the woods near Saint-François-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud until summer 1838, when he returned to Québec. Despite these activities during the rebellion, Morin only spent 10 days in prison following his 1839 arrest; there was, quite simply, too little evidence against him.

The Reformer

Following the rebellions, Augustin-Norbert Morin suffered from poor health and finances, and he returned to law to make ends meet. However, the Patriotewould not stay away from politics for long. In the years following the rebellions, the British government adopted a plan to unite Lower and Upper Canada, a divisive plan that could potentially endanger the survival of French Canada. After a little convincing from his friend Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine, Morin returned to the political ring.

Like many of his peers, Morin’s attitude towards union evolved. Though he was initially in favour of it, believing that it could create a fruitful relationship between reformers in Upper and Lower Canada, he was against its final draft. Like many, he opposed the fact that both colonies were given equal representation in the united Legislative Assembly, despite Lower Canada’s significantly larger population. He even stated: “I am against the Union and its principal points as I believe every honest Lower Canadian must be.” Such a statement would suggest that he had more in common with the Parti rouge. In fact, Morin was even a speaker at the Institut canadien, the original meeting place of the party. However, according to historian Brian Young, a spirit of compromise defined Morin’s post-rebellion attitudes. Though he may not have agreed with the Reformers on every point, he wanted to “convince the authorities of their error and give them the necessary time to repair [the union]…I am for peace, union and harmony, if there is a possibility of achieving it.”

In the Legislative Assembly, Morin again kept very busy. In 1842, he was commissioner of the crown lands; he drafted the School Act of 1845; he was Speaker of the Assembly; and in 1851, he replaced La Fontaine as premier of Canada East after La Fontaine retired. He led the government first with Francis Hincks (1851–54) and later with Allan Napier MacNab (1854–55). During this time, he adopted several reforms that were popular with the Parti rouge, further gaining the support of Reformers and liberals in Canada East. In 1852, for instance, he took a series of steps to reform the much-hated appointed Legislative Council. By 1856, a year after he retired from politics, the Assembly finally reformed the appointed council, introducing elected seats. In 1854, his government also formally abolished the seigneurial system in 1854, ridding the Parti rouge of yet another political campaign argument.

The Civil Code of Lower Canada

Though his health forced him to step down from politics in 1855, Augustin-Norbert Morin did not retire. In fact, he had one more significant contribution left to make in Canadian history. In 1859, he was named, along with Charles Dewey Day and René-Édouard Caron, to the commission that codified the laws of Lower Canada and created the 1866 Civil Code of Lower Canada (see Civil Code). This was one of his greatest achievements. Morin approached the task with great vigour and attention to detail. According to Jean-Marc Paradis, Morin was fully devoted to the task: he “set out the law as established by judicial decisions based on a library of more than 400 legal works.” Unfortunately, Morin was not there the day that his years of work became law in the colony; he passed away in July 1865.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom