Early Life

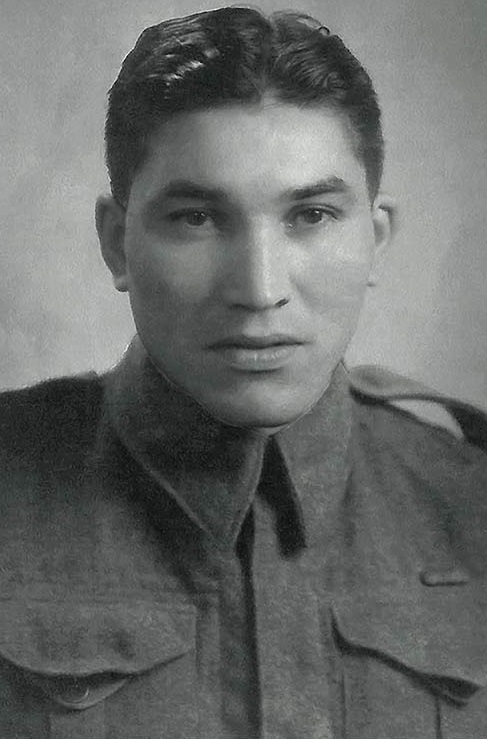

Born in Grouard, Alberta, Charles Tomkins was one of ten children and three stepchildren. His Métis parents were Isabella and Peter Tomkins Jr., both of whom spoke the Cree language and taught their children to do the same. According to the Tomkins family, Charles’s grandparents, Marie and Peter Tomkins Sr., also reinforced the importance of learning Cree. This firm grip on the language made Charles a prime candidate for code talking during the Second World War.

Enlistment and Training

After marrying Lena Anderson in 1939, Charles Tomkins joined the Canadian Army to serve in the Second World War. Six months later, he was called to London, England. Charles recalled the sea voyage as miserable. More than 800 servicemen spent 11 days crowded in a ship, eating only salt herring and beets. After landing in Scotland on Christmas Eve in 1941, Charles was assigned to the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, stationed in England. (See also Indigenous Peoples and the World Wars.)

The Canadian High Command in London issued a secret summons to Charles and about 100 other Indigenous soldiers. They were not told the purpose of the meeting; even Charles’s commanding officer did not know the reason. Upon their arrival, the Canadian Armed Forces divided the soldiers into groups based on the Indigenous languages they spoke.

Charles was paired with a Cree man from Saskatchewan. To test their fluency, the pair received messages in English to translate into Cree. Charles and his partner returned accurate translations and were told that they would soon serve as code talkers — translators of top secret Allied military communications. (See also Cree Code Talkers.)

Indigenous languages were an essential part of a larger Allied plan to hide information about troops and supplies from enemies. While Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan were able to break certain Allied codes, they were not familiar with Indigenous languages in Canada. Therefore, languages such as Cree helped the Allied forces to cleverly disguise important information.

Code Talker Duties

Having first trained with the Canadian Army, Charles was assigned to the US 8th Air Force and the 9th Bomber Command in England. Together with about five other Cree-speaking men from neighbouring areas, Charles began his role as a code talker.

The messages he and the others translated contained vital information about Allied forces, including orders for troop movement and the identification of supply lines or aircraft that were to carry out bombing runs from England. After Charles translated the messages into Cree, they were sent to battlefields in Europe, where another code talker translated them back into English and sent them to military commanders.

Shirley Anderson, Charles’s niece, explained in a Readers Digest article (2017) that since many military terms such as “tanks,” “bombers” and “machine guns” did not exist in Cree, Charles and his partners had to use pre-existing words for non-military subjects in new ways. For example, the code word for the Spitfire plane became iskotew, meaning “fire.” Similarly, the Mustang aircraft was pakwatastim, “wild horse.” To indicate how many aircraft the military had spotted, code talkers would include the appropriate description and number in Cree.

Charles saw action in France, Germany and Holland. In total, six children of the Tomkins family served during the Second World War.

Oath of Secrecy

Charles’s family was unaware of his role as a code talker until well after the war. His brother Jimmy only learned about his brother’s service in 1992, after the two had watched Windtalkers — a film about Navajo code talkers in the American military. The rest of Charles’s family learned of his involvement in 2003, just two months before he died at age 85, when two representatives from the Smithsonian Institution came to Calgary to interview him about the Cree code talkers program. Sworn to secrecy during the war, Charles only revealed the truth about his service towards the end of his life. Some code talkers died without ever having told family and friends of their work.

Little documentation about the efforts of code talkers exists in Canada. Related documents remained highly classified until the Canadian government released them in 1963. Even then, information about code talkers from Canada — such as, for example, how many contributed to the Allied effort during the Second World War — remains sparse, given the fact that these code talkers served with the American military. Moreover, American books and films on code talkers tend to primarily highlight their Navajo counterparts.

Postwar Service

Charles returned to Canada after the war. Struggling to find work, he re-enlisted in the Canadian Army. First stationed at the Currie Barracks in Calgary, Charles served in the armed forces for another 25 years in different regiments including The Sherbrooke Fusiliers, Royal Canadian Army Service Corps and the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. Charles later became a corporal.

Death

Charles died at the Peter Lougheed Centre, a hospital in Calgary. He was survived by adopted daughter Adele and numerous nieces and nephews, and predeceased by his son, Ronald. Charles is buried in the Veterans Field of Honour section of the Queen’s Park Cemetery in Calgary.

Legacy

Charles Tomkins is the subject of a 2016 short documentary, Cree Code Talker, directed by Alexandra Lazarowich, and produced by Cowboy Smithx, with support from the National Film Board and Aboriginal Veterans Society of Alberta. The film shows how Charles’s skills in language, translation and teaching helped the Allies convey important strategic messages during the Second World War.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom