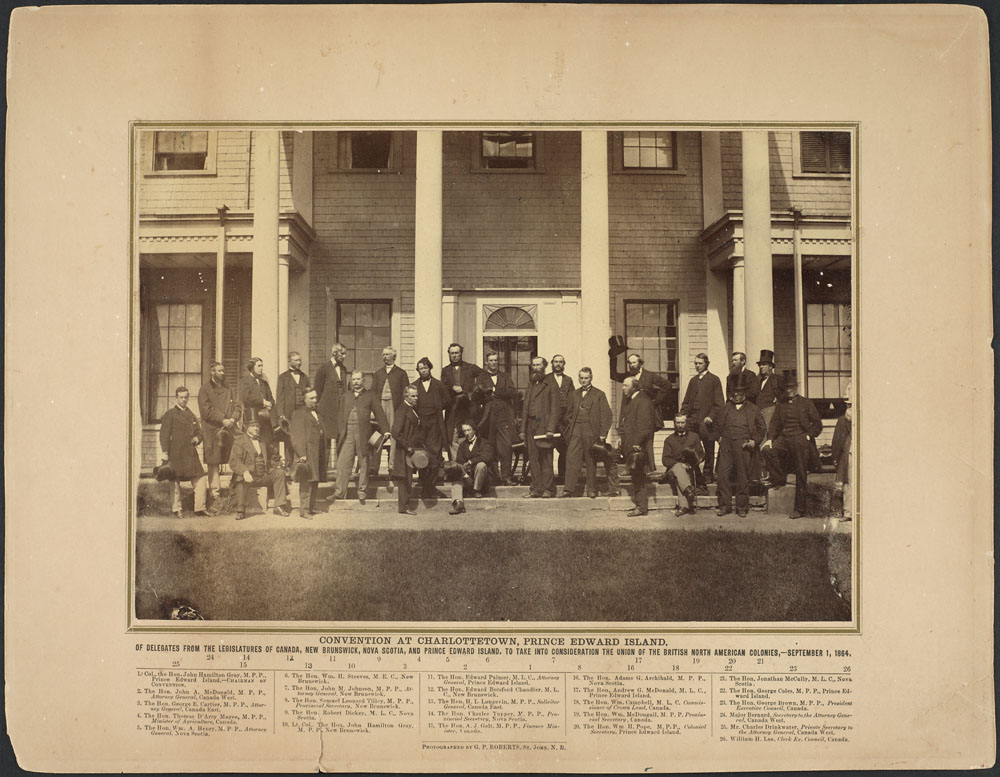

The Charlottetown Conference was a first step toward Confederation. It was held 1–9 September 1864 in Charlottetown. Follow-up meetings were held the following week in Halifax, Saint John and Fredericton. It was all organized by leaders from New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. The purpose was to discuss the union of their three colonies. A group from the Province of Canada convinced them to unite all the British North American colonies. The meeting was followed by the Quebec Conference (10–27 October 1864) and the London Conference (December 1886–March 1867). They all led to Confederation on 1 July 1867.

This article is a plain-language summary of the Charlottetown Conference. If you would like to read about this topic in more depth, please see our full-length entry: Charlottetown Conference.

A Social Affair

Talks in Charlottetown were held in Province House. The schedule was from Thursday, 1 September 1864, until Wednesday, 7 September, with a break on Sunday. Much feasting also took place during the meetings. This helped everyone to get to know one another.

On Thursday, 8 September — a holiday — a grand ball was held for the delegates at Province House. It went on late into the night and early morning. Supper was served at 1:00 a.m. Speeches followed until 5 a.m. Delegates then boarded the SS Queen Victoria for the journey to Halifax. It was the official steamship of the Province of Canada.

Further meetings were held in Halifax, Saint John and Fredericton. They ended on 16 September. The talks formally ended on 3 November 1864 in Toronto, after the Quebec Conference.

Background: Maritime Union

In 1862, the Province of Canada had refused to pay part of the cost of the Intercolonial Railway. It ran from Halifax to Quebec City. This caused the Maritime colonies to talk about merging into a single unit. They hoped this would give them political strength and help attract investment. But overall support for Maritime union did not run deep.

Canadian Fears

The Province of Canada’s interest in a federal union with the Maritimes was mainly due to outside threats. A huge army was formed in the United States during the American Civil War. At the same time, Britain wanted to reduce the costs of keeping its North American colonies. These factors led to fears in Canada of being annexed (taken over) by the US. (See Annexation Association.) The province had also had a series of weak and unstable governments. This fueled the demands for change and for a new political structure.

The three Maritime provinces each had five delegates in Charlottetown. Each group included members of the government and the opposition. Canadian leaders learned of the conference in Charlottetown through Samuel Tilley. They seized on the chance to attend. They sent a group that hadn’t been invited. But they were welcomed anyway.

Middle-aged and Ambitious

The Fathers of Confederation weren’t a bunch of old men. They were middle-aged. They hoped to someday run the system they were creating.

There were some notable omissions from the group from the Maritimes. For starters, they were all men. No one spoke for the region’s large Irish communities. Andrew Macdonald was the only Catholic. The united province was to be called Acadia. But there were no francophones from the Maritimes. Indigenous people and Black Canadians were excluded from public life at the time.

Experienced Players

Confederation with the Province of Canada had been debated for many years in the Maritimes. It was mainly seen as a long-term issue.

Nova Scotians Charles Tupper and Jonathan McCully wanted to unite all the provinces. John Hamilton Gray of New Brunswick had called for a federal union as far back as 1849. Samuel Tilley was guardedly in favour. John Hamilton Gray of PEI claimed to have dreamed since his youth of a great BNA nation.

Edward Barron Chandler, Tilley and William Henry Steeves of New Brunswick, plus Adams Archibald and McCully of Nova Scotia, had helped negotiate the Intercolonial Railway with Canada. They were well equipped to assess Canadian ideas. Joseph Howe was a high-profile Nova Scotian Liberal. He was asked to take part by Tupper. But he was absent on an official mission. He promised to co-operate with a plan for Maritime Union. But he was against a wider Confederation. (See Confederation’s Opponents.)

Canadian Visitors

Eight of the 12 members of the Province of Canada’s Great Coalition went to Charlottetown. This was a sign that they meant business. Legal knowledge and political smarts made John A. Macdonald a key figure. George Brown was the main Reformer (Liberal). He spoke for Canada West.

Financial expert Alexander Galt was from Canada East. So too was Irish Catholic writer Thomas D'Arcy McGee. The sole francophones, George-Étienne Cartier and Hector-Louis Langevin, were both fluent in English. (It is unlikely that French was spoken at the meetings.) William McDougall and Alexander Campbell were also there from the Province of Canada.

The Canadians were mostly in their 40s. The youngest, Langevin, was 38. The oldest, Cartier, turned 50 during the meetings. McGee was the only one who knew the Maritimes well. The Canadians also brought two senior bureaucrats with them, plus a shorthand writer. This implied that they hoped to hammer out a detailed scheme for Confederation.

Meetings Begin in a Muddle

The Nova Scotia and New Brunswick groups arrived on 31 August. they found that no hotel rooms had been booked for them. Charlottetown was packed with people who came for a circus. So, there were few vacancies. In contrast, the Canadian group was much more efficient. They arrived the next morning on the Queen Victoria. It served as a floating hotel.

On 1–2 September, the Maritime group met at Province House. They elected Premier Gray as chairman. They reviewed the goals of the three groups. The Nova Scotia government had approved the idea of Maritime Union. But the New Brunswick and PEI groups only had a mandate to take part in talks. From the start, the Conference had a problem of differing goals.

Marriage Banns Proclaimed

The Canadians were welcomed on the afternoon of Friday 2 September. There was more talk and speeches the next morning. The Canadians then hosted a champagne luncheon on board the Queen Victoria. ( See The Charlottetown Conference of 1864: The Persuasive Power of Champagne.) Someone quoted words from the Anglican marriage ceremony. They said that if anyone knew any reason why the provinces should not be united, let him speak now or forever hold his peace. The Maritime group had not yet agreed to Confederation. But the moment was seen by George Brown as proof that they would. All-day sessions were also held Monday and Tuesday.

A Gentle Ultimatum

The order of the Canadian group’s contributions are unclear. But it seems that Cartier spoke first. He wanted Confederation to guarantee French Canadian autonomy. He also wanted the Maritimes to retain local control over regional issues. (See Distribution of Powers.)

Brown had been the driving force for Confederation in the Canadas. He stressed that Canada West wished to run its own affairs. He wanted Confederation to be reached within a year. If it wasn’t, the Great Coalition would make the Province of Canada into a local, two-headed federation. Thus, the Maritimers were given a gentle ultimatum: If they were in favour of Confederation, it was now or never.

The previous speakers had focused on provincial rights. John A. Macdonald then spoke of the importance of a strong central government. Also important was Alexander Galt’s speech on 3 September. He outlined how the provinces would be financed. The frugal Maritimers were alarmed by Canada’s high public debt. But Galt defended it. He argued that Canada’s higher population meant that its debt per person was smaller than that of New Brunswick.

In 1862–63, the Province of Canada had refused to pay some of the cost of the Intercolonial Railway. But now, it offered to guarantee construction of the line under Confederation. Five-sixths of the cost, double the previous share, would be paid for by the more prosperous Canadian taxpayers. It was an attractive offer.

Conditional “Yes”

Tupper wasn’t sure he wanted to abandon Maritime Union. But Tilley thought the Maritimes would get better terms if they were separate provinces. Tilley saw the idea of regional union as a backup if the larger scheme failed. He argued that the three Maritime colonies could easily be merged into one single province after Confederation. His fellow delegates generally agreed. They convinced Tupper not to press his motion to a vote.

The Maritime groups had a private talk on 7 September. They then gave the Canadians their answer. They were unanimous in joining a federation if they were satisfied with the final terms.

The agreement extended beyond the general principle of Confederation. The Intercolonial Railway was central to the deal. The Maritimers would accept Confederation if they got the railway. The Canadians would only build it as part of a political union. They all also agreed upon having sectional equality in the upper house (Senate) of the new government. This meant each region would get an equal number of seats. (See Rep by Pop.)

Another meeting was then held in Quebec City in October 1864. The finer points of Confederation were worked out there.

See also Great Coalition of 1864 (Plain-Language Summary); Quebec Conference (Plain-Language Summary); London Conference (Plain-Language Summary); Quebec Resolutions (Plain-Language Summary); Confederation (Plain-Language Summary).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

![The province of Canada [cartographic material]](https://d2ttikhf7xbzbs.cloudfront.net/media/media/bf6a8447-8306-4749-bb63-2f6129eb20a6.jpg)