The election of 1896 divided the country — along linguistic lines — over the Manitoba schools question. It also ended 18 years of Tory rule, ushered Wilfrid Laurier into power, and brought about the short, 68-day prime ministerial term of Sir Charles Tupper.

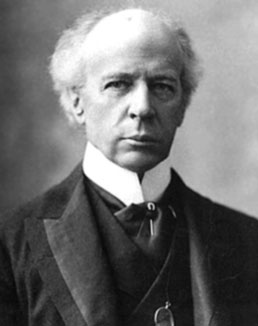

Charles Tupper

As the prime minister approached the podium, the audience response was mixed. Sir Charles Tupper was applauded by his Conservative followers and loudly jeered by the Liberals in the crowd. It was four days before the 1896 election, and Tupper was determined not to let the Liberal horde shout him down. For three or four minutes he waited, his face expressionless, for the din to subside. Finally, he began to talk. He was taunted throughout the speech. Taking advantage of his well-known self-esteem, the crowd yelled "I, I, I" every time Tupper referred to himself. When he mentioned the leader of the opposition, Wilfrid Laurier, the Liberals rose to their feet and cheered.

The interruptions were constant and so loud that, in the words of one journalist, "It was impossible to hear him, even at a distance of less than ten feet." Though he was tired and old, just a few days shy of his 75th birthday, the prime minister persevered, lashing out at his critics. "You men who are making these interruptions are the most block-headed set of cowards that I ever looked upon."

He deserved a better reception. Sir Charles Tupper had committed himself to a lifetime of public service. Working first as a physician, he turned his mind to politics in the years before Confederation, eventually becoming premier of Nova Scotia. He was a Father of Confederation, afterward becoming a prominent member of the Cabinet of Sir John A. Macdonald. In the Commons, Tupper was known for speeches that may have lacked grace, but were full of thunder. An architect of Macdonald's National Policy, a system of tariffs designed to stimulate Canadian industry, Tupper eventually became the old leader's heir apparent.

Relations between the two then became strained. Tupper lost his place as Macdonald's designated successor and left Ottawa for London, to serve as Canada's High Commissioner. When Macdonald died in 1891, some Conservatives wished for Tupper to come home to lead the government. But he had alienated many with his ambition and inability to compromise. His opponents ensured that he was not asked to take the top job.

Manitoba Schools Question

Over the next four years, the Conservatives went through three leaders. Tupper returned to Canada in December 1895 to find the government on its deathbed, in his words, "utterly demoralized." Once seen as the natural governing party of Canada, the Conservatives were now poorly led and incapable of handling the politically charged Manitoba schools question.

In 1890, the Manitoba legislature had ended public funding for the province's separate Catholic school system. Under the Constitution, the federal Parliament could pass remedial legislation, overriding provincial laws that affected minority education rights. Ottawa, however, was in a difficult position, not wanting to offend the Catholic minority in Manitoba or the Catholic majority in Québec, and equally determined not to upset Protestants in Manitoba and the other English-speaking provinces.

For years, the government avoided the issue publicly, while an agonizing internal war was fought. Finally, in January 1896, merely months before the election, seven members of the government resigned. After prolonged negotiations, they agreed to return on condition that Prime Minister Mackenzie Bowell step down at the beginning of the election campaign and turn the government over to Tupper.

Tupper's Election

Tupper immediately returned to Cabinet as solicitor general, prime minister in all but name. He set out to pass a remedial bill that would re-establish publicly funded Catholic schools in Manitoba. He tried to ram the bill through Parliament, but a Liberal filibuster prevented the legislation from making its way through the House of Commons before the parliamentary term expired. Parliament was dissolved on 24 April, marking the beginning of the election campaign, though Tupper did not officially become prime minister until 1 May.

One of Tupper's priorities was to recruit star candidates. For Québec, he worked to lure Adolphe Chapleau, a senior Conservative who had served both as premier and as a member of the federal Cabinet. Tupper thought that his old colleague would be able to lead the Tories to victory in Québec, but Chapleau, who had now been out of federal politics for four years, resisted the call.

Tupper had more success with Hugh John Macdonald, Sir John A.'s son, who joined the Cabinet as minister of the interior. He may not have inherited his father's political acumen, but the Macdonald name still held sway and the son resembled the father, sharing his most distinctive facial feature. Some predicted that Hugh John's presence would make the difference and that the Tories would "win by a nose."

Liberals Remake Image

The Liberal party was in much stronger condition. Laurier was everything that Tupper was not. Elegant and charming, he possessed a gift for finding compromise between apparently irreconcilable opponents. During his nine years as leader, Laurier had reshaped his party. He'd made a loose alliance of provincial Liberal parties into a national organization. He'd recruited Ontario Premier Oliver Mowat, who announced that he would serve in a Laurier Cabinet.

Laurier weaned the Liberals from their free trade tradition. Many Canadians had voted Conservative in 1891 in opposition to the Liberal plans for freer trade with the United States. Laurier had distanced his party from the policy, depriving the Tories of a key campaign issue. In Québec, the abandonment of the party's old trade policy helped Laurier to woo moderate Conservatives to his cause, as did his insistence that the party shed its anti-clerical tradition. Among those switching sides was Israël Tarte, a master tactician who left the Conservatives and agreed to run the Liberal campaign in that province.

On the Manitoba schools issue, Laurier had the luxury enjoyed by all opposition leaders. There was no need to enunciate his own position; he could simply attack the weaknesses in the government's policy. He spoke as little as possible about Manitoba schools during the campaign, and what he did say was vague. His approach, he said, would be to conduct an investigation, seek out the facts, and then use conciliation. He called it "sunny ways," evoking the Aesop fable in which the sun and the wind compete to see which can force a man to take off his coat. The wind makes the man to cling more tightly to his garment, while the sun's warmth induces him to take it off.

The Catholic Church preferred the windy way. The Québec bishops issued a pastoral letter, read from the pulpit in every Catholic Church early in the campaign, saying Catholics had an obligation to vote for candidates who supported remedial legislation to restore the education rights of Manitoba Catholics. Bishop Louis-François Laflèche of Trois-Rivières went further, declaring that Laurier was an enemy of the church and that voting for him was a sin. Tarte was not worried. "Elections are not won by prayers," he said.

Laurier Era Begins

As usual, Tarte's political judgment was sharp. On election day, 23 June, the Liberals secured a decisive victory, carrying 118 seats to the 88 for the Conservatives and 7 for others. Laurier's home province had made the difference. In Québec, the result was 49–16 for the Liberals, while in the rest of the country the Tories had a three-seat edge.

True to his personality, Tupper was not about to surrender without a fight. While his party appealed the results in those Québec ridings where the final count was close, Tupper continued on as prime minister. He even prepared a long list of patronage appointments, including senators and judges, which the governor general refused to approve. Finally, on 8 July, Tupper realized that he had no choice but to resign and turn the government over to Laurier.

Laurier would go on to head the government for the next 15 years, the longest uninterrupted term for a Canadian prime minister. Tupper also holds a record: at a mere 68 days, he had the shortest term of any prime minister in our history.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom