We love them and we hate them.

They bring out the best in us, and the worst.

They frequently divide us, and sometimes — as with John Diefenbaker's thunderous victory in 1958 — federal elections succeed in uniting the country behind a single impulse, or a single voice.

One thing's for sure: amid all the change that has swept across Canada since Confederation, there has remained one steadfast certainty — that every few years, we ordinary citizens have the right to collectively choose who should govern us. Today, this privilege is not shared by billions of the world's people. How lucky that our democracy endures.

When Canadians return to the polls, not only will we be carrying out the business of voting, we'll be writing a new chapter in Canada's rich electoral history. It's an intriguing story, filled with high stakes, hijinks and high passions, not to mention a colourful cast of political characters.

Here are some famous elections from the past, and how they changed Canada...

1891

"I am a good deal discouraged as to our future," wrote Sir John A. Macdonald. "Not that the country has gone or is going against us, but because our ministry is too old and too long in office."

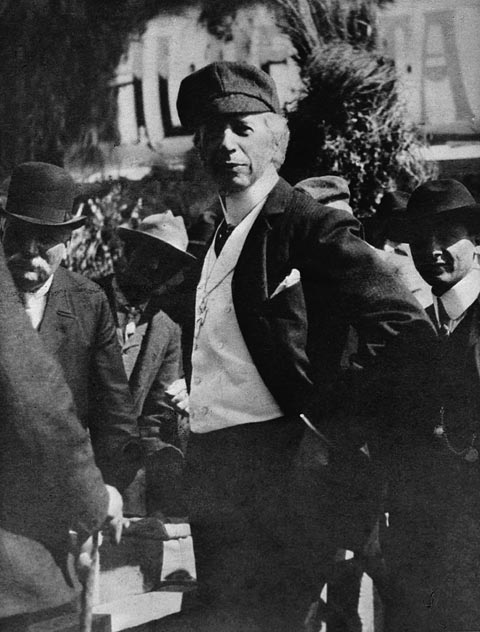

By 1890, Macdonald’s Conservatives had been in power for 18 of Canada’s 23 years in existence, and the Prime Minister, dubbed the “old chieftain,” was 75 years old. But it was less the weariness of age and more the rumblings of scandal — what had also thrown the Tories from government in 1873 — that pushed Macdonald to dissolve Parliament and call an early election in 1891.

In his first campaign as Liberal leader, Wilfrid Laurier found his wedge in Macdonald's longstanding National Policy — which levied tariffs on imported goods to protect Canadian manufacturers from American competitors — and ran on a policy of unrestricted reciprocity (free trade) with the US.

An inveterate politician, Macdonald turned the Liberals' plank into a question of national survival, arguing that free trade with the Americans was the definition of treason, a sure way to sell out the country. He rode that stance along a gruelling campaign trail, rallying voters behind "The Old Flag, The Old Policy, The Old Leader" and won a majority of seats in the House.

Though it would not be the last time an election hinged on free trade, it would, however, be Macdonald’s last political outing. He died that June — bringing one era to a close and ushering in a new one.

Reciprocity or the National Policy?

"As for myself, my course is clear. A British subject I was born — a British subject I will die. With my utmost effort, with my latest breath, will I oppose the 'veiled treason' which attempts by sordid means and mercenary proffers to lure our people from their allegiance." - Prime Minister John A. Macdonald

Macdonald convinced voters in 1891 that Wilfrid Laurier's offer of reciprocity with the Americans would undermine Canadian sovereignty. He attacked Laurier and the Liberals as economic sellouts and branded himself as the defender of Canada. It worked.

1896

The election of 1896 divided the country — this time, along linguistic lines. It also ended 18 straight years of Tory rule and brought Wilfrid Laurier to power.

In the four years following Sir John A. Macdonald’s death, the ruling Conservatives had gone through three leaders before settling on Sir Charles Tupper. Inheriting a crumbling party and the divisive Manitoba schools question, which centred on linguistic and religious minority education rights, Tupper took on a very tall task.

Surefooted and charismatic, Laurier had reformed the Liberal party during the Tories’ years of decline. In the 1896 campaign, he enjoyed a luxury held by all opposition leaders: there was no need to enunciate his position on the Manitoba schools issue; he could simply attack the weaknesses in the government's policy.

The Liberals won a majority government on election day, Laurier's home province making the difference; in Québec, the result was 49–16 in seats for the Liberals.

Laurier would go on to head the government for the next 15 years, the longest uninterrupted term for a Canadian prime minister. Tupper also holds a record: at 68 days, the shortest term of any prime minister in our history.

1917

The election of 1917 was the ugliest in Canadian history. It was fought and won over the issue of conscription.

Conservative Prime Minister Robert Borden believed conscription was the only way for Canada to continue its commitment to the First World War. Knowing the matter would split the country and cost him support in Québec, Borden forged the Union Government. A coalition of like-minded Conservatives, Liberals and independents, the Unionists pushed through partisan legislation that gave soldiers and their female relatives the right to vote — extending the Union support base — while removing the vote from immigrants who had come to Canada since 1902 from enemy nations, and from conscientious objectors.

The election campaign was nasty. Unionists attacked the Liberals' patriotism, while pro-conscription newspapers thundered, "Every vote cast for a Laurier candidate is a vote cast for the [German] Kaiser." Meanwhile in Québec, the Union Government struggled to find candidates; and those brave enough to run under the conscription banner were threatened and attacked.

Borden's Unionists swept the English-speaking regions, returning to Parliament with a majority of 153 seats, including only three from Québec. A lasting consequence of the election was the political isolation felt by Québec, a fact that would hurt Conservative fortunes there, and haunt Canadian unity, for generations.

The federal election of 1917 "mirrored the war overseas: vicious, unrestrained, and with blood everywhere." - Historian Tim Cook

1925 and 1926

The elections of 1925 and 1926, and the rocky parliamentary proceedings in between, were led by two very different contenders for top office: one intellectual and cold, the other deliberately vague and hiding his ambition — Conservative Arthur Meighen and Liberal William Lyon Mackenzie King.

The 1925 election returned 116 Conservatives, 101 Liberals and 28 Progressives, Labour and Independents to the House of Commons. Many assumed that King, the defeated prime minister, would resign. Instead, he hung onto power in the House, with the help of Progressive and Labour MPs.

When a customs scandal broke the following year and his government faced defeat, King went to Governor General Viscount Byng to seek a new election. Byng declined the Prime Minister's advice, sparking the King-Byng constitutional crisis. Byng correctly believed that Meighen's Conservatives should have the chance to form a government, so he handed the reins to the Tories. But Meighen himself soon lost the confidence of the House.

Another election was finally called for September.

King appealed throughout the 1926 campaign to Canadian nationalism — saying that interference by a British Governor General with the rights of Canadians to govern themselves was unacceptable. The message was constitutionally wrong, but politically it had broad appeal. It distracted voters from the Liberal customs scandal, and it brought King a clear victory.

He would govern uninterrupted until 1930, and again from 1935–1948.

1957 and 1958

By 1957 the Liberals had been in power in Ottawa for 22 years. The party was arrogant, and Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent — benevolent "Uncle Louis" — was getting old. But so great was Canada's postwar prosperity, there seemed no reason to think people would vote for change.

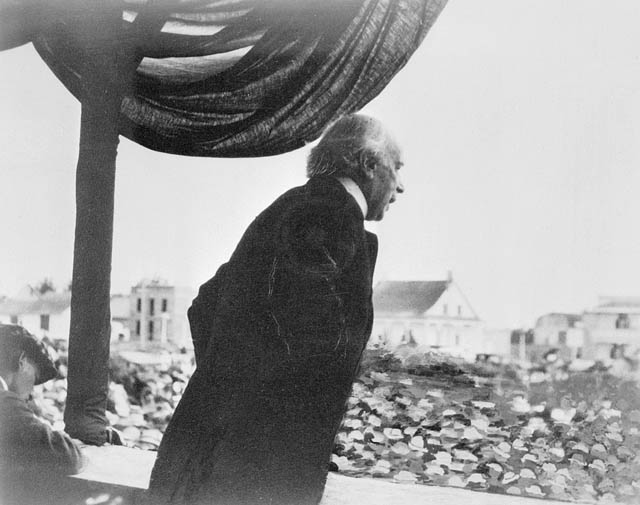

Then, out of the blue, came John Diefenbaker, selected as Tory leader only a year earlier. His charisma, dynamic oratory, and his Prairies populism awoke the electorate, and made St-Laurent look tired and dowdy by comparison.

Diefenbaker and his bold plan to develop the North inspired Canadians and convinced them it was time for a change. The Tories won a minority in 1957 and a landslide majority the following year. The long, Liberal hegemony dating back to William Lyon Mackenzie King was over.

Largest Majority Ever

The Conservatives won 208 seats in the election of 31 March 1958, the largest majority ever.

1979 and 1980

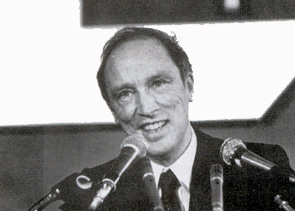

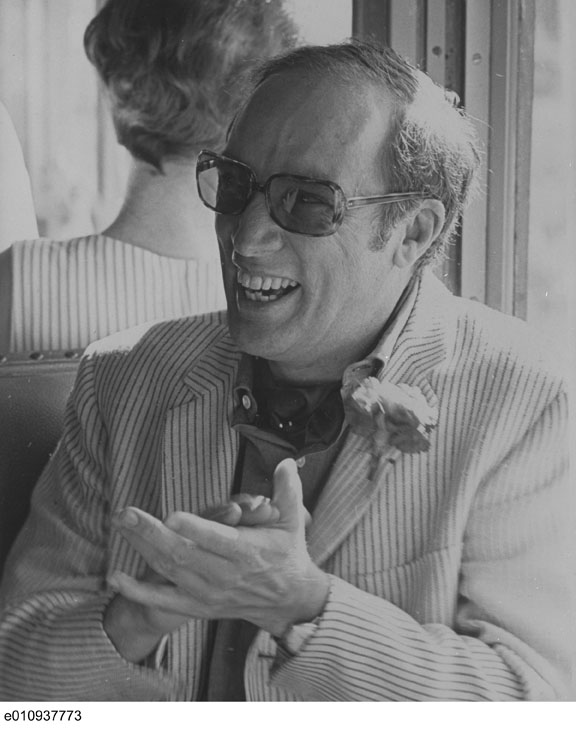

Trudeaumania had long since faded by 1979. After 11 years in office, Pierre Trudeau's Liberal regime was long in the tooth, and bruised by its economic battles against inflation.

Joe Clark, an Albertan — the new, 39-year-old leader of the Progressive Conservatives — persuaded Canada to give him a chance. He won a minority government in May 1979, triggering Trudeau's immediate resignation from politics.

Seven months later, the Tories introduced a tough, deficit-fighting budget that hiked gasoline taxes, at a time when consumers were already reeling from skyrocketing oil prices. The budget was defeated in Parliament, and Trudeau was lured back from private life to fight the ensuing election for the Liberals.

The 1980 campaign was fueled by the spectre of an independent Québec. The separatists had come to power in that province promising a referendum on sovereignty. Many Canadians felt the country needed a savvy francophone leader who could lead the federal side in the looming battle in Québec.

The result, on national election night in February, was a solid Liberal majority. The 1980s dawned in Canada with Trudeau back in the prime minister's residence at 24 Sussex Drive, even before Joe Clark had managed to get comfortable.

1988

John Turner’s return to political life, as Liberal leader in the mid-1980s, hadn't gone well. He was plagued by internal party strife, personal back pain and a public image as a weak and bumbling leader.

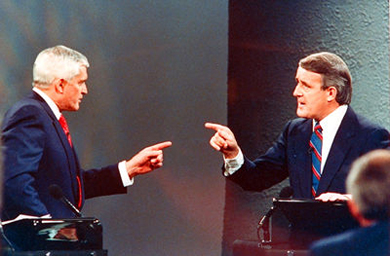

So it surprised everyone — in the election campaign of 1988, during the televised leaders' debate — when he tore into Prime Minister Brian Mulroney over the Tory government's new free trade deal with the United States.

"I happen to believe you have sold us out," Turner said. "We built a country [and] with one signature of a pen, you've reversed that."

"Mr. Turner," Mulroney shot back, "you do not have a monopoly on patriotism."

Mulroney would go on to win the election — his second majority government — but the televised debate would go down as one of the great political encounters in Canadian history.

More importantly, free trade became the single, defining issue in the 1988 campaign. It was the last election fought not over wedge politics or personalities, but on the basis of a big, overarching, national idea.

"I happen to believe you have sold us out."... "You do not have a monopoly on patriotism."

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom