Early Life

Hugh Burnett was born on a farm outside of Dresden, Ontario, to Robert and Myrtle (née Carter). His parents descended from enslaved African Americans who had escaped to Canada in the mid-1800s (see Black Enslavement in Canada). Dresden was one of several end points for the Underground Railroad in southwestern Ontario. As refugees from enslavement and free African Americans arrived and settled there, a significant Black community took shape in and around Dresden (see also Josiah Henson).

From a young age, Burnett was aware of the effects of anti-Black racism. One Sunday, when he was 16, Burnett stopped his truck to help a travelling motorist who had run out of gas. The man was so grateful that he insisted on taking Burnett for lunch. While he already knew that he could be refused service, Burnett thought he might be accepted in the company of this White stranger. He was still refused service, and the incident outraged him. Historian James Walker recalled: “At that time, he dedicated himself to doing something about this.” Burnett resolved to fight racism in his community.

Racial Discrimination in Dresden

By the 1940s, the Black community in Dresden made up about 17 per cent of the local population. Though Black and White people attended school together and often lived near each other, racist attitudes and practices were reflected in some intense discrimination toward the Black community, leaving them with much less public access. Among other things, most business owners in Dresden refused service to Black people. In the 1940s, such anti-Black racial discrimination was not unique to Dresden. Systemic racism was a significant barrier for Black people, Indigenous peoples and other communities of colour across Canada (see Prejudice and Discrimination). What was unique about racial discrimination in Dresden was, as James Walker put it, “its absoluteness.” Walker explained that “not a single pool room would allow Black people… not a single restaurant, not a single barber shop where they could get their hair cut.” Except for the Catholic church, churches essentially barred Blacks. However, also unique in Dresden was the tenacity and leadership skills of Hugh Burnett in fighting racism and discrimination.

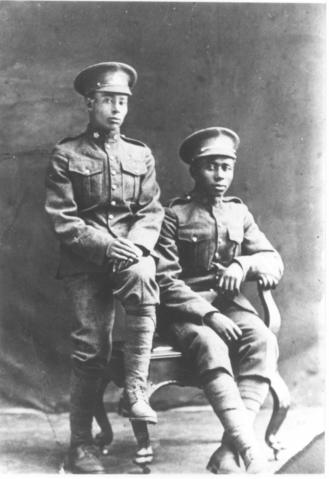

An incident in 1943 strengthened Burnett’s commitment to challenging the situation in Dresden. At the time, 25-year-old Burnett was living in Windsor, Ontario, with his wife, Beatrice, and working for the Ford Motor Company. In Dresden to visit family, he went to a local restaurant wearing his army uniform. (Burnett had enlisted when the Second World War began and was later discharged for medical reasons.) To his dismay, the owner would not serve him. Burnett promptly wrote to the federal Minister of Justice, Louis St-Laurent, informing the minister that, by historian James Walker’s account, “even in uniform a Black man could not be served in any Dresden restaurant.” The Deputy Minister’s reply simply stated that there was no law against racial discrimination in Canada (see also Fred Christie Case).

“The Dresden Story”: Fighting for Civil Rights with the National Unity Association

In 1948, Burnett moved back to Dresden with his wife and children to join his uncles, William, Percy and Bernard Carter, who were spearheading a group to address racism in town. They called the group the National Unity Association (NUA). It was mostly made up of Black farmers and tradespeople from Dresden and the surrounding area. Burnett became the group’s secretary, key organizer and lead spokesperson. Once in Dresden, he also established a successful carpentry business.

Dresden Story, Julian Biggs, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

In 1948, the NUA lobbied the Dresden town council to pass a bylaw against discrimination in local businesses. After initially refusing, council agreed to put the idea to a referendum the following year. Historian James Walker suggests it was the “first and only time in Canadian history where racism has been put to a ballot.” Thanks to the efforts of Burnett and others, discrimination in Dresden began to get widespread media attention, including a high-profile exposé in Maclean’s magazine in 1949 entitled “Jim Crow Lives in Dresden.” While the heightened publicity was a success for the NUA, the referendum was not: townspeople voted five to one against an anti-discrimination bylaw. This was roughly the ratio of White to Black residents of Dresden.

In 1950, Burnett and the NUA joined a coalition of human rights activists pushing for provincial anti-discrimination legislation. In 1951, as a result of their campaign, the government of Premier Leslie Frost enacted the Fair Employment Practices Act, which forbid discrimination in employment. As Burnett pointed out in a letter to Frost, however, this law did not address discriminatory practices in public service — a central issue in Dresden. By 1954, the NUA began working in earnest with the Toronto Joint Labour Committee for Human Rights to push for further anti-discrimination legislation in Ontario.

In March 1954, Burnett was a lead speaker in a civil rights delegation to Premier Frost and his cabinet, making the case for a law against discrimination in public service. According to media reports, Frost was emotionally moved by Burnett’s testimony that day. Soon after, the Frost government introduced the Fair Accommodation Practices Act, which forbid discrimination in public service and housing on the basis of race, religion and other criteria. This was a victory for Burnett, the NUA and their allies.

Restaurant Sit-Ins in Dresden

The Fair Accommodation Practices Act became law in June 1954. In Dresden, however, Burnett and the NUA quickly realized that many business owners were not going to comply with the new law. Two local restaurants were particularly notorious for continuing to refuse service: Kay’s Café, owned by Morley McKay, and Emerson’s Restaurant, owned by Matthew and Anne Emerson. Burnett and the NUA devised a tactic: they would go to these restaurants, take a seat and ask for service. When they were refused, they lodged formal complaints through the Fair Accommodations Practices Act. Historian James Walker notes that Burnett’s tactic resonates with the famous sit-ins of the American civil rights movement. In fact, Burnett’s 1954 sit-ins took place in Ontario more than five years before they were prominent in the United States.

Thanks to tireless advocacy by Burnett, the NUA and its allies, the issue continued to get national publicity throughout 1954. Despite the formal complaints piling up, the provincial government did not, at first, lay charges against the Dresden restaurants.

Under public scrutiny, Dresden business owners began simply closing shop when they saw NUA members coming. This made it difficult for the NUA to keep building its case.With the help of Sid Blum and the Toronto Joint Labour Committee, the NUA devised a new strategy: They began coordinating tests involving out-of-towners unfamiliar to Dresden business owners. A reporter from Toronto would accompany and document the tests, allowing the NUA to continue to gather evidence of discrimination, thereby keeping the issue in the media spotlight.

One test case in late 1954, involving Bromley Armstrong (a Black trade unionist and human rights activist) and Ruth Lor (a Chinese Canadian University of Toronto student and secretary of the University of Toronto Student Christian Movement), resulted in high-profile media coverage and charges against Kay’s Café owner Morley McKay. McKay was ultimately found not guilty in this case.

Burnett and the Toronto Joint Labour Committee did not give up. In November 1955, another test case proved more successful. Two Trinidadian University of Toronto students, Jake Alleyne and Percy Bruce, were refused service at Kay’s Café and they lodged complaints. In early 1956, McKay was once again charged. He was finally found guilty and forced to pay the required fines.

On 16 November 1956, members of the NUA went to Kay’s Café. For the first time ever, they were served. The court case against McKay was a significant victory for Burnett, the NUA and the rights and freedoms of Black communities in Dresden and across Ontario.

Personal Life

Burnett’s activism took a toll on him and his family. They were targeted with anonymous threats and violence. Soon after the NUA’s 1956 victory in Dresden, Burnett was forced out of town in search of work, his carpentry business boycotted by angry White locals. In a CBC documentary, Burnett’s daughter Patricia recalled how his activism affected her mother: “She was the one that was compensating when my father’s income got lower and lower, and using fewer potatoes and fewer onions to try to produce a meal.… She came into that marriage wanting family… and family was set aside to do this thing.” Despite these difficult years, Patricia admired her father’s tenacity and commitment to justice: “I don’t know if I believe in destiny, but I think that he was on this earth to do what he did. He had to do it.”

After moving to London, Ontario, in 1956, Burnett kept a low profile, continuing his carpentry business and working for various companies. Though he never again came into the public eye as he had with “The Dresden Story,” according to those close to him, he continued to support anti-discrimination organizing in Ontario throughout his lifetime. He died in 1991 at age 73.

Significance

Hugh Burnett was a tireless force for change both in his community and in the fight for human rights legislation in Ontario. Burnett’s efforts with the NUA to bring attention to racial discrimination in Dresden held a mirror up to Canadian society and forced a public reckoning with systemic racism in Ontario and Canada. He was instrumental in the push that led to both the Fair Employment Practices Act of 1951, and the Fair Accommodation Practices Act of 1954. This provincial legislation paved the way for the more comprehensive human rights protections in Canadian law, including the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Reflecting on the Fair Accommodations Practices Act in a 1954 news documentary, Burnett was both pragmatic and hopeful:

“It has been stated that you can’t make a law to make one man love another. I think Premier Frost knew very well that the law would not do that, but it would eliminate the act of discrimination. And of course our personal feelings will come into it later. We will learn to like each other.”

Honours

In 2010, a plaque was erected in Dresden by the Ontario Heritage Trust, in honour of Hugh Burnett’s legacy.

Journey to Justice, Roger McTair, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom