Debates about the rights and place of Jewish children in Montreal’s denominational public schools peaked in the 1920s. These debates divided Jewish, Protestant and Roman Catholic communities. After a decade of failed negotiations and legal challenges, the Quebec government adopted a bill aimed at establishing a separate Jewish school board with the same rights and privileges as Protestant and Catholic boards. The Act was widely criticized and the law was repealed. The unequal treatment of Jews and other religious minorities in Quebec public schools continued until 1997 when the British North America Act was amended to enable the creation of secular linguistic boards.

Background

The British North America Act of 1867 gave provinces authority over education with a significant, overriding exception. Section 93 of the Act protected the religious educational rights of the Protestant minority in Quebec and the Roman Catholic minority in Ontario. In Quebec, a dual confessional school system, controlled by Protestants and Roman Catholics, became entrenched in law. Although Jews and members of other faiths could attend either Protestant or Catholic schools, they did not possess equal educational rights.

In order to access public schooling, Montreal’s minority Jewish community had to seek arrangements with the Protestant or the Roman Catholic school boards. The minority Protestant board was willing to accommodate other faiths in order to boost its revenue and influence. However, the larger Catholic board’s attitudes ranged from indifference to hostility. As a result, Jewish children enrolled in Protestant schools.

Changing Demographics

In the early 1900s, thousands of Jewish immigrants fleeing persecution, pogroms and economic hardship in Eastern Europe and Russia settled in Canada. (See Immigration to Canada; Refugees to Canada.) By 1901, there were 6,941 Jews in Greater Montreal, but the largest immigration cohort was yet to come.

The newly arrived immigrants were more diverse than the older, established community. Most spoke Yiddish as well as other foreign languages. They also brought a wide range of political, social and religious views with them. As the Jewish community grew, both Protestants and Catholics felt increasingly threatened. Quebec Catholics, predominantly conservative and religious, were suspicious of immigrants whose ranks included liberal and secular Jews. Protestants began to feel outnumbered and financially disadvantaged in their schools.

As property taxes funded Quebec’s confessional public schools, Jewish homeowners paid taxes to the Protestant school board in exchange for the right to elementary schooling. However, many newcomers were renters, not taxpayers. As the number of Jewish students in Protestant schools grew, so did the financial responsibilities of the board. Tensions rose and culminated in the Pinsler case in 1901.

Pinsler Case and Education Act, 1903

The son of Jewish immigrants, Jacob Pinsler won a scholarship to attend high school. (See Immigration to Canada.) However, the Protestant school board refused to honour the award. The board argued that the Pinslers did not financially contribute to the school as they were renters, not property owners. Therefore, the family was not entitled to educational privileges. The Pinslers and Jewish community sued; however, the Quebec Superior Court upheld the board’s position as only Protestants and Roman Catholics had constitutional educational guarantees. (See also Court System of Canada.) Jewish children did not possess the same legal rights and entitlements.

Fallout from the Pinsler case led to the adoption of the Education Act in 1903. The Act stipulated that Jews would be considered Protestants for educational purposes, and the Protestant board would receive funding based on enrolment. Nevertheless, problems persisted and dissatisfaction on all sides increased.

Jewish School Question

The Jewish School Question in Montreal was the dominant issue in the Jewish community from 1920 to 1931. The established community, favouring integration, was committed to strengthening and enforcing the 1903 Education Act. Newcomers advocated for the creation of a separate school system under Jewish control. Steeped in controversy, the question divided a community unable to achieve consensus.

The right of Jewish children to public schooling was also widely debated throughout Quebec. The Protestant school board and Roman Catholic Church held strong positions, and the Quebec Legislative Assembly intervened. Eventually, the issue made its way through the courts, attracted widespread media coverage, and was exploited by virulent anti-Semites.

By 1921, Jews had become the third largest ethnic group in Montreal. The Jewish population in Greater Montreal had grown to 45,802 and represented 6.13 per cent of the total population of the city. Newer immigrants, known as the “downtown” group, were concentrated in the east end while the older community or “uptown” group had migrated to the west end. (See also Immigration to Canada.)

In 1923, 12,000 Jewish children attended Protestant schools in Montreal out of a total student population of 32,000. In some schools, Jewish children constituted a majority. Despite the provisions of the 1903 Education Act, few Jewish teachers were hired and Jews were not permitted to serve as school commissioners. Jewish students were also segregated in some schools.

The Protestant board maintained that the presence of Jewish teachers and students compromised the quality of education and Christian values. The board also declared that Jewish taxpayers covered only half the cost of educating Jewish students, a claim which was challenged in the Jewish press. Unwilling to compromise on any issues, the Protestant board asked the legislature to repeal the 1903 Act.

Within the Jewish community, divisions simmered. Representatives of the uptown group and the Jewish Educational Committee fought to remain in the Protestant system. This group opposed separate schools, fearing potential isolation and inferior educational standards. Representatives of the downtown group and the Jewish Community Council maintained that keeping Jewish students in Protestant schools instilled Christian values and undermined Judaism. Hirsch Wolofsky, editor of the Kenneder Adler (Jewish Daily Eagle), and prominent businessman Lyon Cohen (grandfather of Leonard Cohen) attempted but failed to broker compromise positions.

In 1924, Quebec Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau established a Special Commission on Education. It included three Jewish, three Protestant and three Roman Catholic representatives. After months of deliberations, the commissioners remained at an impasse. Taschereau subsequently referred the 1903 Act to the Quebec Court of Appeal.

Court Rulings

The appeal court concluded that the 1903 Education Act contravened section 93 of the British North America Act and was therefore invalid. (See also Court System of Canada.) Jews had no legal rights to attend Protestant schools, teach or serve as commissioners. The court also ruled that the Quebec government did not have the authority to set up separate schools.

The government appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of Canada. In 1926, the Supreme Court upheld the appeal court rulings on section 93 but concluded that the provincial government had the right to establish separate schools.

In 1928, the case was referred to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, the highest legal authority at the time. The Privy Council concurred with the Supreme Court.

David Bill

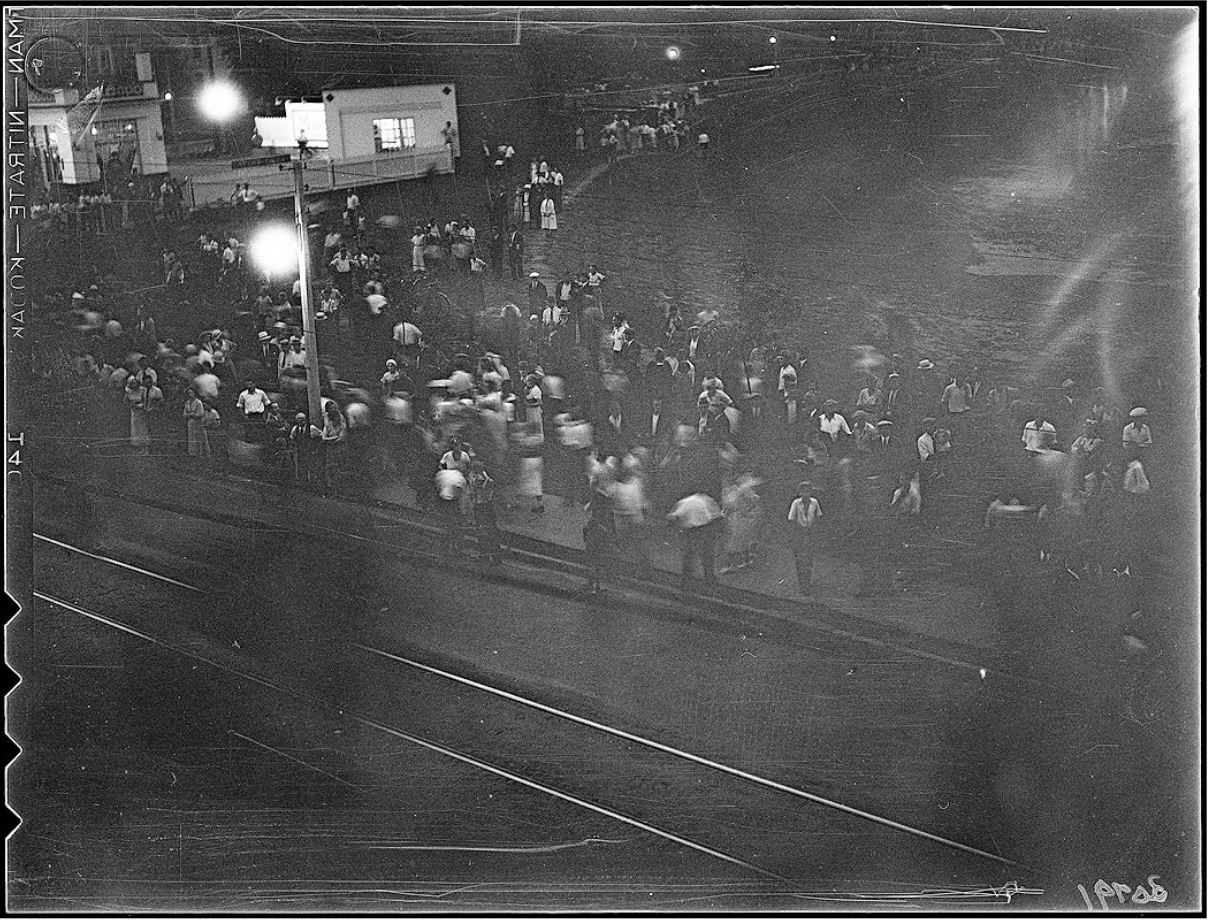

In April 1930, the Liberal government of Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau adopted legislation enabling the creation of a Jewish school board. Opposition to the David bill — named after Provincial Secretary Athanase David — erupted. Factions within the Jewish community continued to disagree, the Roman Catholic Church denounced the bill and French-Canadian nationalist extremists protested. (See also Francophone Nationalism in Quebec.) Identity issues and growing anti-Semitism fueled debates and inflamed public opinion.

A fear of creeping secularism motivated the Quebec Catholic Church’s opposition to the bill. The Church was unwilling to relinquish its control of education. (See also Ultramontanism.) Some insisted that granting equal rights to Jews would dilute the Catholic character of Quebec and threaten the survival of the Church. Some francophone nationalist extremists feared that legal recognition of Jews would encourage ethnic diversity and destroy French-Canadian culture.

The most vicious attacks came from the anti-Semitic, racist movement led by Adrien Arcand. Writing in Le Goglu and Le Mirroir, Arcand characterized Jews as inhuman parasites, thieves, members of an inferior race and the root of all evil. He denounced Premier Taschereau and other prominent francophones such as Henri Bourassa, accusing them of allowing Jews to infiltrate government, corrupt youth and prey on Christians. Le Goglu published violent, hateful caricatures of Jews and ridiculed political leaders who supported the David Bill.

Aftermath

One year after its adoption, the David Bill was repealed in 1931. Under the terms of the 1930 statute, government-appointed Jewish commissioners were legally required to continue negotiations with the Protestant and Catholic school boards. As pressure mounted and support for the David Bill collapsed, the commissioners entered into an agreement with the Protestant board. However, they obtained few concessions other than an end to segregation. Discriminatory practices in hiring and religious education continued as did taxation without representation.

In the end, the Protestant board benefitted the most from this arrangement. The board received increased funding, grew in size and became the de facto public school system for all students other than Roman Catholics. At the same time, the board retained its Christian character.

The Jewish community lost its battle for equal status in education. The creation of a bilingual or trilingual Jewish board could have also improved relations between the Jewish community and the French Catholic majority. Instead, the integration of Jewish students into the English Protestant system widened the gap.

The Jewish School Question was ultimately resolved in 1997 when section 93 of the British North America Act was amended. This enabled the creation of religiously neutral linguistic school boards to replace confessional schools in Quebec. The transition to a secular public school system granted legal educational rights to the Jewish community in Quebec after more than 100 years of inequality.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom