Now 14 km long and an average of about 50 m wide, it is, among other things, a navigable waterway boats can use to bypass the Lachine Rapids, though these are passable only in small crafts with very shallow drafts. A series of five locks in total provides elevation changes of 12 to 15 m. While the canal’s structures look recent and are now used exclusively for recreational boating, they actually conceal a 300-plus-year history, including an industrial past of which only a few vestiges can still be seen.

A living legacy of Canada’s industrial history, the Lachine Canal was declared a Canadian national historic site in 1996. The Lachine Canal National Historic Site is administered by Parks Canada, a federal agency.

Background

The idea for a canal on the island of Montréal emerged toward the end of the 17th century. Ville-Marie, as it was known under the French regime, was a hub for the fur trade and was an area where the Huron, Algonquin, Iroquois and French all coexisted. However, there was still major tension at the time, much of it resulting from relations between the French and the Iroquois (see Aboriginal-French Relations).

The canal project was originally intended to power the water mills and to increase the flow of goods along the St. Lawrence River. François Dollier Casson, superior of the Sulpicians at the time, oversaw the early construction. Unfortunately, that work was interrupted in August 1689 following an attack by the Iroquois. The subsequent ratification of a treaty between the French and the Iroquois, the Peace of Montréal, 1701, eased the hostilities.

The Montréal Sulpicians, who were the main authority at the time, tried repeatedly to relaunch the project in the first half of the 18th century, but a lack of capital and financial resources impeded any progress. The technologies available at the time also made it extremely difficult to excavate rock, a material engineers had yet to learn how to work.

England took possession of the territories of New France in the second half of the 18th century. When the United States invaded Canada in 1775, the ensuing war made it clear just how critical it had become to reinforce the thoroughfares all along the St. Lawrence (see American Revolution). Therefore, construction of an initial series of canals between Montréal and the Great Lakes began in 1783.

This construction was followed by a dramatic increase in the flow of goods transiting through these canals, as well as an increase in vessel tonnage, creating the need to develop and build new canals. This led to a second series of canals, Ottawa’s Rideau Canal and the Lachine Canal in Montréal.

Construction

In 1819, two years before construction began, John Richardson, along with engineer Thomas Burnett and seven Montréal businessmen, founded the Company of the Proprietors of the Lachine Canal. Their efforts to finance the canal failed, and it was only in 1821 that the federal government established a commission to begin the work. The commission had virtually the same membership as the Company of the Proprietors of the Lachine Canal and was headed by Richardson, with Burnett as senior engineer. The Lachine Canal was inaugurated four years later, in 1825. In its initial form, it was 14.6 m wide, 13.4 km long and 1.4 m deep.

The aim of this construction was to build a major North American economic empire on the St. Lawrence River, which, as a result of its geographic location, had a number of significant comparative advantages that also spurred its economic development. One such advantage was its continental penetration, as it connects the Atlantic Ocean — a gateway to Western Europe — to the Great Lakes, which are more than 1,500 km inland. The Great Lakes being located largely in the United States further increased the project’s economic potential.

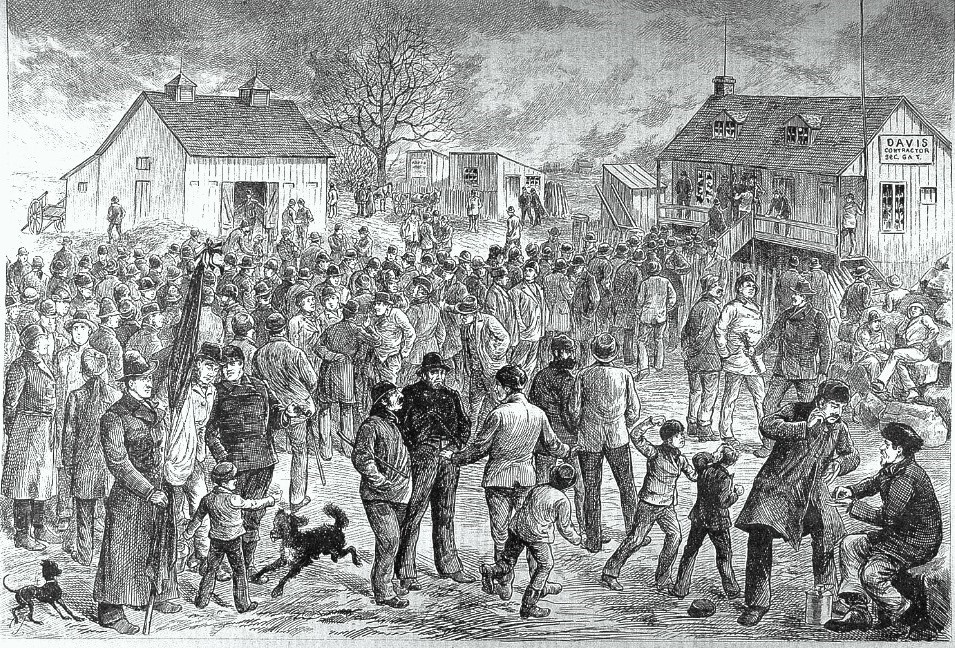

Nearly 500 workers, most of whom were Irish, worked on the Lachine construction site. During the 19th century, the British colonial authorities heavily favoured Irish emigration to Canada. Propelled by a poor quality of life as well as the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s, the Irish came to Canada in droves, providing an ample and inexpensive English-speaking workforce, much to the delight of British officials.

Most of these immigrants settled near the large building sites of the day, either the Victoria Bridge or the Lachine Canal site, thereby contributing to the gradual growth of the fief of Nazareth. Now known as Griffintown, Nazareth was the first and largest industrial neighbourhood of this period in Canadian history.

There were internal divisions in this workforce, however, leading to serious conflict. In addition to francophone-anglophone tensions, there was also the Catholic-Protestant divide among the Irish. Appalling working conditions compounded this social unrest. By 1842, the tension was palpable, with increasingly frequent and sometimes violent clashes between managers and workers. Jealousy quickly spread among the workers, who realized they were clearly not being treated as well as other area residents.

In 1843, politicians did their utmost to ensure an expansion of the Lachine Canal. This effort was intended to reduce the impact of major technical advances in competing US waterways and to boost the regional economy, which was recovering from the depression of 1841 to 1843, yet because the government lacked the funds to complete the work, the project was handed over to a private company. Mounting social tension, however, hampered the work’s progress, and early June 1843 saw the outbreak of the bloodiest labour conflict in Canada’s history to date, at a time when any kind of trade unionism was still prohibited. Lasting just over 20 days, the conflict, which also involved workers from the Beauharnois Canal, left several dead and even more injured.

Expansion and Development

With the area around the Lachine Canal seeing increasing industrial development, the Montreal and Lachine Railroad began laying its first railroad tracks in the vicinity in 1847.

The second and final phase of canal expansion stretched from 1874 to 1885. At the end of this period, the Lachine Canal had an average width of 45 m and an average depth of 4.3 m. The rail system was also effectively integrated into the canal in 1875 with the construction of railway lines alongside it, allowing goods to be transported more quickly and efficiently almost anywhere in North America. As a result, this remained the largest industrial area in all of Canada until 1959.

An important date in the history of the Lachine Canal, the year 1959 marked the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway, which soon replaced the canal. The seaway’s locks, which were over 223 m long and 24 m wide, and its depth of 9.1 m made it possible for much larger vessels to transit from the Atlantic all the way to the Great Lakes via the St. Lawrence.

Use of the Lachine Canal quickly declined until 1970, when its closure was officially announced. A major factor in its decline was that its main infrastructures required urgent repair work. The largest boats still using the waterway often caused damage because they exceeded the canal’s capacity.

National Historic Site of Canada

The Lachine Canal’s story does not end there, however. In 1974, the Canadian government decided to redevelop the site in an effort to reduce the amount of unused urban space. After four years of cleanup and landscape renovation, and in recognition of the importance of its historic economic role, the site came under the administration of Parks Canada. A bike path was also created along its banks (see Bicycling). These new uses allowed metropolitan area residents to reclaim the land since virtually all remaining infrastructure had been abandoned.

The historic value of the site has also been demonstrated in numerous Parks Canada studies focusing on the canal’s physical structures and on the important role it played in Canada’s industrialization and urbanization. The Lachine Canal was declared a National Historic Site of Canada in 1996.

The government finally reopened the canal for recreational boating in 2002, allowing boaters to use its locks to sail upstream and downstream along the southwestern part of the Montréal island. Today, the canal’s whole landscape has been transformed. The Griffintown neighbourhood, which had been abandoned by most of its inhabitants following the massive closure of businesses in the area, rose from the ashes with a new boom in real estate and trade, as well as a lively arts scene. One example of its revitalization is Cité du Multimédia, an industrial park that plays host to a number of businesses on the cutting edge of technology.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom