Mary Ann Camberton Shadd Cary, educator, publisher, lawyer, abolitionist (born 9 October 1823 in Wilmington, Delaware; died 5 June 1893 in Washington, D.C.). Mary Ann Shadd became the first Black woman in North America to publish and edit a newspaper, The Provincial Freeman. As one of the first Black newspaperwomen in North America, Shadd promoted the abolition of slavery and the emigration of African Americans to Canada (see Black Canadians; Black Enslavement in Canada; Slavery Abolition Act, 1833). She also advocated on behalf of women’s rights (see Women’s Movements in Canada).

Early Life and Education

Mary Ann Shadd was the first of 13 children born into a prominent abolitionist family in Delaware on 9 October 1823. Her father, Abraham Doras Shadd, was a shoemaker in Wilmington, Delaware, and a leader among Delaware’s free Black community. Her mother was Harriet Parnell from North Carolina. Their home was a stop on the Underground Railroad that assisted freedom seekers out of Maryland and Delaware into the Free State of Pennsylvania and beyond.

Growing up in such an activist household had a profound impact on Shadd’s outlook and future activism. However, the educational opportunities for Black people in Wilmington were scant in the 1820s and 1830s. Shadd’s parents decided to move the family to West Chester, Pennsylvania, where their children could receive an education at a Quaker-sponsored school. Remarkably, at the tender age of 16, Shadd returned to Wilmington and opened a school for Black children. In so doing, she was one of many free Black women who lent their skills and education to “uplift” their race.

Move to Canada West

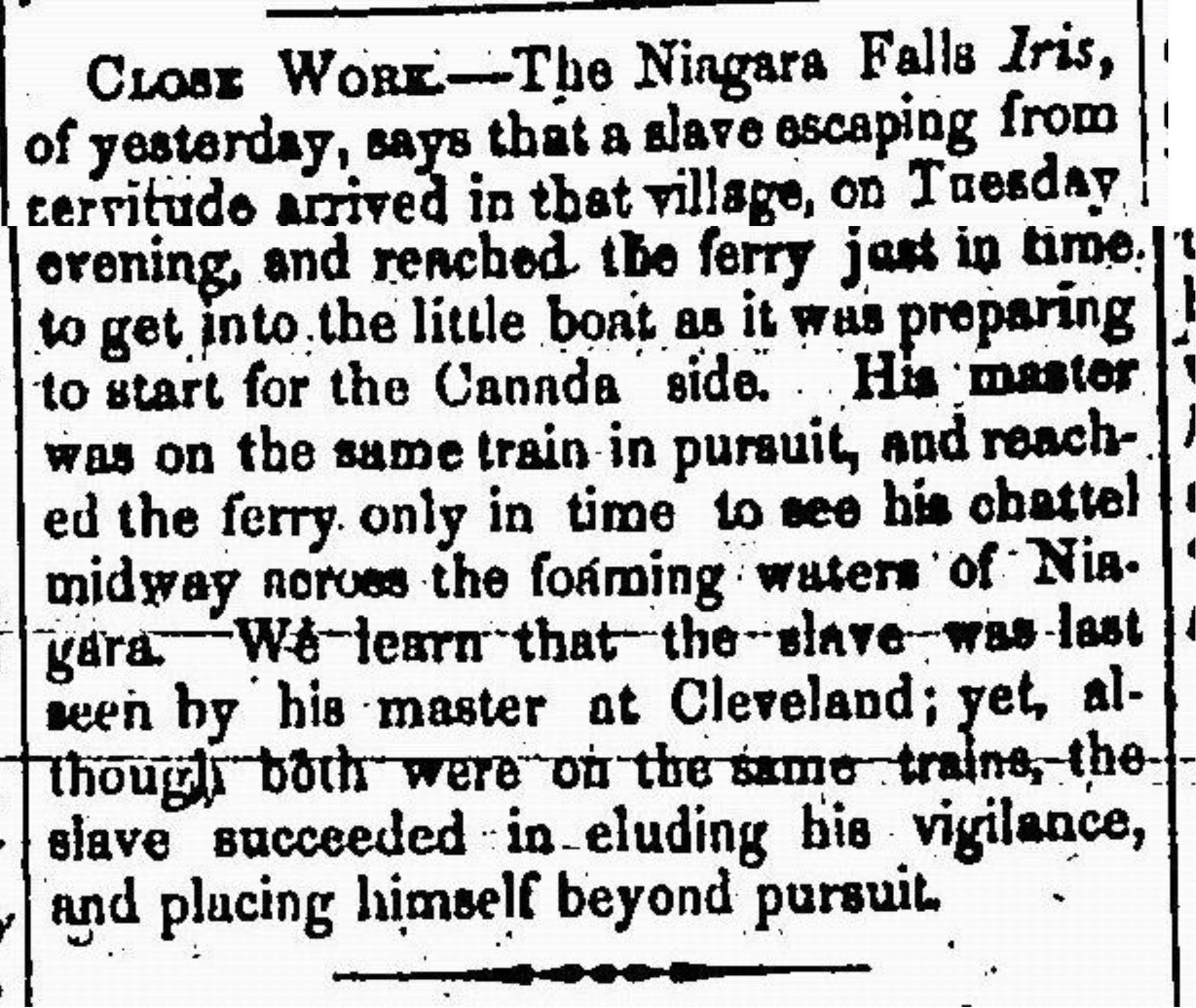

By 1850, Mary Ann Shadd had been teaching for over 10 years in various towns and cities on the eastern seaboard of the United States, including Norristown, Pennsylvania; Trenton, New Jersey and New York City. Her teaching services were requested by Henry and Mary Bibb, Black newspaper publishers and activists living in Sandwich, Canada West, now part of present-day Windsor, Ontario. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 had just been passed by the United States Congress. The Act not only allowed slave hunters and owners to track fugitives (escaped enslaved persons) into free states, but also compelled state governments and ordinary citizens to participate in the capture and return of fugitives. Even free African Americans were sometimes kidnapped and sold into slavery. As a result, thousands of formerly enslaved people living in freedom in northern states moved across the border into Canada. There slavery had been officially abolished by Great Britain in 1833, to take effect 1 August 1834 (see Slavery Abolition Act, 1833).

Did you know?

Shadd first met Henry and Mary Bibb in 1851 at the North American Convention of Coloured Freemen. The convention was hosted in St. Lawrence Hall in Toronto.

Shadd heeded the call of the Bibbs and in 1851 moved to Windsor, where she opened a private school for the children of freedom seekers. It was officially an integrated school — Shadd staunchly opposed racially segregated schools (see Racial Segregation of Black Students in Canadian Schools). As education was not publicly funded at the time, parents were to pay one shilling per week in school fees, but many could not afford to do so. Consequently, Shadd pursued financial assistance from the American Missionary Association, an anti-slavery religious organization. Despite her meagre salary, she provided students with a first-class education, including reading, grammar, spelling, geography and arithmetic, later adding history and botany to the curriculum.

In addition to her position as a teacher, Shadd was involved in community affairs. In 1852, she published A Plea for Emigration; or Notes of Canada West, which touted Canada West (Ontario) as a desirable destination for enslaved and free African Americans experiencing increasing restrictions on their lives. However, her public outspokenness and willingness to challenge male community leaders, both Black and white, caused controversy. Disputes with the Bibbs over the question of segregated schools, the management of the Bibbs’ Refugee Home Society land scheme and the society’s practice of “begging” for funds spilled onto the pages of the Bibbs’ newspaper, the Voice of the Fugitive. This publicized feud led to Shadd being fired from her teaching position. It also changed history.

The Provincial Freeman

Mary Ann Shadd decided that she would establish her own newspaper where she could control how her ideas and opinions were shared. She solicited support and encouragement from the Black community in Windsor and her family and friends in West Chester, Pennsylvania. A first edition of The Provincial Freeman appeared on 24 March 1853. Initially, Shadd had asked Samuel Ringgold Ward, Black abolitionist and lecturer for the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada, to lend his name and expertise as editor. Alexander McArthur, a White Congregational minister, was named corresponding editor. Shadd was aware that her name on the masthead could alienate a readership that considered newspapers and editorships to be men’s affairs.

Following the publication of the newspaper’s first edition, Shadd spent a year collecting subscriptions and building interest in her paper by taking to the lecture circuit. On 25 March 1854, The Provincial Freeman began publishing weekly out of Toronto. With this undertaking, Shadd became the first Black woman in North America to establish and edit a newspaper and one of the very early newspaperwomen in Canada (see Newspapers in Canada:1800s-1900s).

Under Shadd’s direction, The Provincial Freeman was an anti-slavery newspaper and it strongly advocated Canada West (Ontario) as a place for Blacks to settle (see Emigration). The paper’s motto, “Self-reliance is the true road to independence,” emphasized the importance of Black self-sufficiency and integration into Canadian society. Readers were advised to insist on fair treatment, and to take legal action if all else failed. The paper also championed women’s rights and provided a forum for Black women, showcasing their accomplishments and benevolent activities. (See also Women’s Movements in Canada.)

Some of the leading Black leaders of the day, such as Reverend William P. Newman and H. Ford Douglas, were involved as editors or contributors to the paper, along with Shadd herself. The newspaper engaged in investigative reporting and muckraking (a form of exposé journalism). Shadd wielded her pen like a mighty sword, not afraid to attack institutions such as the Black church, or anything and anybody she believed was engaged in wrongdoing. After moving the newspaper to Chatham, Canada West, in 1855, Shadd’s brother Isaac also sat in the editor’s chair, and her sister Amelia and sister-in-law Amelia Freeman Shadd contributed articles and filled in as temporary editors. Mary Ann Shadd often went on speaking tours in Canada and the United States in an attempt to keep the paper financially afloat. However, this was a daunting task, as the newspaper’s target audience had received little if any education and the newspaper was dependent for its readership upon a small, educated elite.

After a valiant effort to keep the newspaper going, The Provincial Freeman succumbed to financial pressure and ceased publication by the year 1860. However, despite criticism and financial troubles, the newspaper’s seven-year publication run was quite an achievement and, according to biographer Jane Rhodes, places it among a small group of influential Black publications, including the newspapers of Frederick Douglass, a well-known African American abolitionist. In addition to providing an important voice for the Black community in Canada, it has provided an invaluable window on that community for modern-day researchers.

The Civil War and Later Years

Mary Ann Shadd married and took the name of Toronto businessman Thomas F. Cary in 1856, and gave birth to two children, Sarah and Linton. Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s personal life was as unconventional as her public life. The couple maintained two residences and often lived apart during their four-year and eleven-month long marriage. Tragically, Thomas Cary died in 1860.

With the death of her husband and the demise of The Provincial Freeman, Shadd Cary’s attention turned increasingly to events in her homeland. She was hired by Dr. Martin Delany to recruit Black soldiers during the Civil War and she later went on to study and practise law in Washington D.C., being one of the first Black women to do so. (See also American Civil War and Canada.) She also became increasingly vocal and active on the issue of women’s suffrage during her later years.

Legacy

Mary Ann Shadd Cary died on 5 June 1893. After a lifetime of achievements and firsts, perhaps her greatest contribution was the role she carved out for herself as a Black woman in the public sphere, whether as a teacher and community activist, writer, newspaper editor, public speaker, recruiting agent for the Union Army or lawyer. By pushing the boundaries and limitations normally ascribed to her race and sex, she blazed a trail not only for Black people but for generations of women. (See also Black Canadians; Black Female Freedom Fighters.)

Among her many posthumous honours, the Mary Shadd Public School opened in Scarborough, Ontario in 1985 and Shadd Cary was designated a National Historic Person in Canada in 1994. On 9 October 2020, she was featured in a Google Doodle on her 197th birthday and in 2021 a post office in Wilmington, Delaware, was named in her honour. In January 2024, ahead of Black History Month, Canada Post released a stamp in honour of Mary Ann Shadd. Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s house on W Street NW in Washington D.C. is a national historic landmark.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom