The Numbered Treaties were a series of 11 treaties made between the Crown and First Nations from 1871 to 1921. The Numbered Treaties cover the area between the Lake of the Woods (northern Ontario, southern Manitoba) to the Rocky Mountains (northeastern British Columbia and interior Plains of Alberta) to the Beaufort Sea (north of Yukon and the Northwest Territories).

The treaties provided the Crown with land for industrial development and white settlement. In exchange for their traditional territory, government negotiators made various promises to First Nations, both orally and in the written texts of the treaties. These include special rights to treaty lands and the distribution of cash payments, hunting and fishing tools, farming supplies, and the like. These terms of agreement are controversial and contested. To this day, the Numbered Treaties have ongoing legal and socio-economic impacts on Indigenous communities. (See also Treaties with Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

(This is a full-length entry about the Numbered Treaties. For a plain-language summary, please see Numbered Treaties (Plain-Language Summary.)

List of Numbered Treaties

The following chart details the year in which each of the Numbered Treaties was signed. Click on Treaties 1–11 to read more about these specific agreements.

|

Treaty Number |

Date of Treaty |

|

1871 |

|

|

1871 |

|

|

1873 |

|

|

1874 |

|

|

1875 |

|

|

1876 |

|

|

1877 |

|

|

1899 |

|

|

1905 |

|

|

1906 |

|

|

1921 |

Historical Context

The years immediately following Confederation were characterized by the Canadian government’s desire to expand westward as a means of securing the nation’s economic future. The lands of the Hudson Bay Company, namely Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory, were of particular interest to expansionists. They were sources of valuable natural resources and vast space, which could be used for European immigration and industrial and commercial developments. With the Americans expanding westward, many Canadian politicians feared their neighbours to the south would annex these lands. (See also Manifest Destiny.) In order to extend its sovereignty over portions of northern and western Canada, the federal government acquired Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory in 1870.

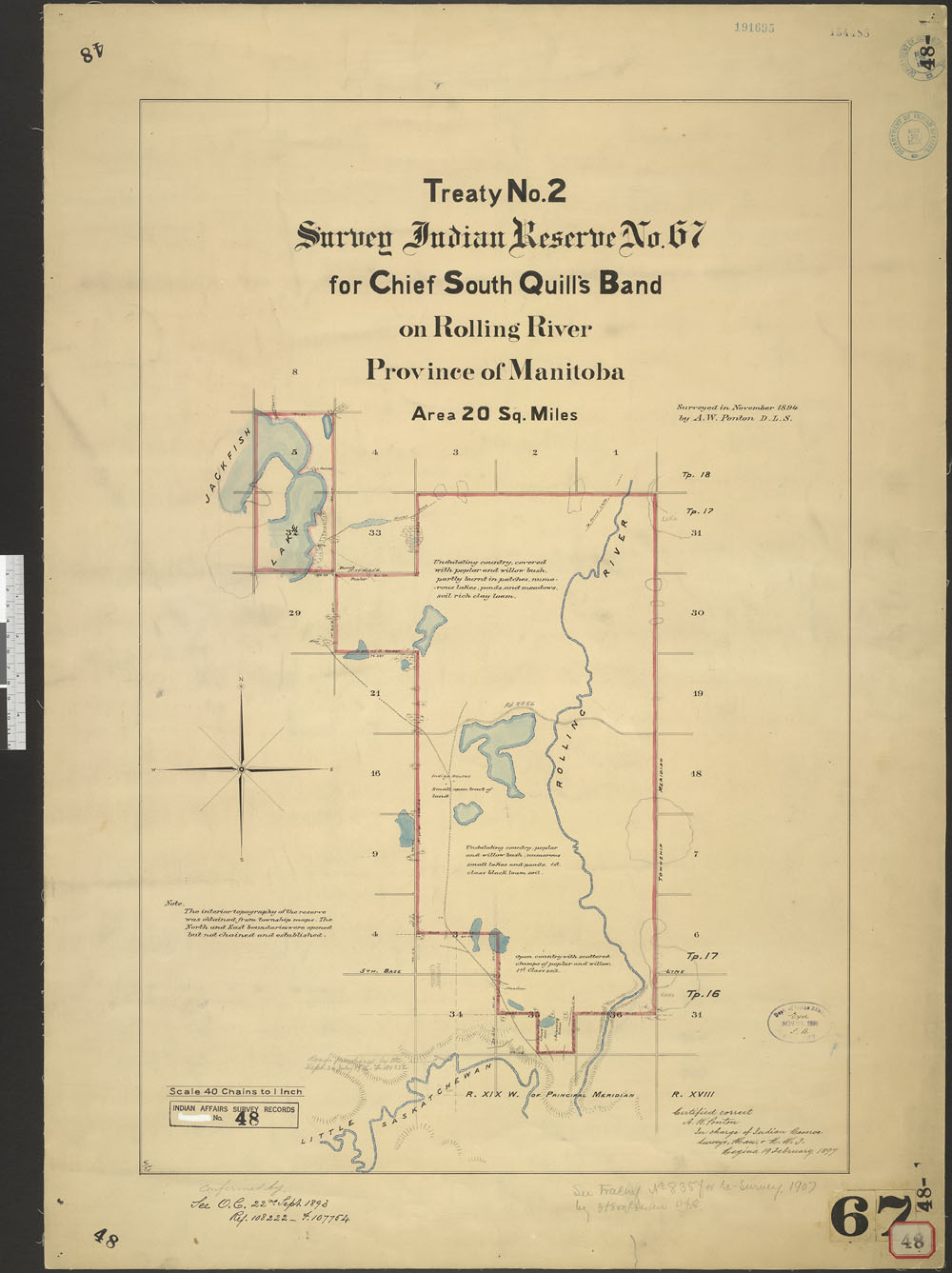

As part of the Hudson Bay Company’s obligations for the transfer of Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory to the federal government, Canada had to address all Indigenous claims to those lands. Based on the model of the 1850 Robinson Treaties, the Crown signed 11 treaties with various First Nations between 1871 and 1921. These treaties would allow the Crown access to, and jurisdiction over, traditional territories in exchange for certain promises and goods, such as reserve lands, annual payments and hunting and fishing rights to unoccupied crown lands.

Purposes and Provisions

Treaties 1 to 7, concluded between 1871 and 1877, solidified Canada’s claim to lands north of the US-Canada border. They also enabled the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway and opened the lands of the North-West Territories to agricultural settlement.

Treaties 8 to 11, concluded between 1899 and 1921, facilitated access to natural resources in northern Canada. They also opened the West for settlement and secured a connection between British Columbia and central Canada.

Similar to other federal Indian policies and programs at the time, the Numbered Treaties were intended to assimilate Indigenous peoples into white, colonial society and culture. The treaties included provisions about education on reserves and also encouraged the farming techniques and settlement patterns of colonials. Indian agents – the Canadian government’s representatives on reserves from the 1830s to the 1960s – implemented government policies. These included provisions of the Indian Act, the day-to-day affairs of Status Indians, and policies like the pass system.

Many First Nation leaders sought to use the treaties as a means of coping with the destruction of traditional economies — notably, the decimation of the buffalo on the Prairies. From some Indigenous perspectives, the Numbered Treaties included a commitment from the Canadian government for the instruction and material aid necessary for transitioning to a new way of life.

However, not all First Nation leaders were satisfied with the treaty terms offered by the government. For example, Plains Cree chief Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear)refused to sign Treaty 6 in 1876, fearing that he and his people would lose their freedom and ability to practise traditional ways of life, including hunting. In another instance, during the negotiation of Treaty 1 in 1871, First Nation leader Ay-ee-ta-pe-pe-tung became so disillusioned with the negotiations that he considered walking away from the bargaining table. In these and similar cases, many Indigenous peoples felt that their concerns were not being taken seriously and that they stood to lose more than gain in the process of treaty negotiations. Although many First Nation leaders signed the Numbered Treaties, most saw no other viable option.

Varied Interpretations

Differing interpretations of the treaties have led to disputes between the federal government and First Nations. Some have argued that since concepts of territory and ownership are different in European and Indigenous worldviews, First Nation leaders did not understand the meaning and implication of such treaty terms as “cede, release, yield up and surrender.” Indigenous peoples may have interpreted the treaties as instruments to share, as opposed to own, the land and natural resources with the colonizers. ( See also Indigenous Territory.) Errors in translation may have also caused misunderstandings.

Another common source of discontent about the treaties concerns what has become known as the “outside promises” — verbal commitments made to First Nation leaders not included in the written treaties. In Treaties 1 and 2, First Nation leaders claimed that the government verbally promised to provide assistance for agricultural development. This promise wasn’t honoured until several years after the treaties were signed, following complaints from affected Indigenous communities. Even then, the government didn’t provide all that it had promised. Verbal commitments that differed from written accounts in the Numbered Treaties remain ongoing issues of dispute and discussion.

Impacts

The Numbered Treaties have had long-lasting legal and socio-economic impacts on First Nation peoples. The creation of reserves, schools and other instruments of assimilation have affected Indigenous cultures, customs and traditional ways of life. In addition, ongoing disputes about the oral and written terms of the treaties pertaining to land use, fishing and hunting rights, natural resource use, and the like, have led to modern land claims. In order to address concerns about treaty fulfilment, the federal government established a policy recognizing comprehensive and specific claims in 1973. The federal department of Indigenous affairs (which has changed names a few times since 1966) is responsible for negotiating treaties. (See also Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Federal Departments of Indigenous and Northern Affairs.)

In spite of inadequacies in the treaty-making process, the Numbered Treaties have helped to guide the relationship between the federal government and First Nation peoples by providing a context of mutual responsibilities and rights. As modern land claims are resolved and concluded, the Canadian government and treaty First Nations work together towards improving the lives of Indigenous peoples.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom