A Heritage District with Numerous Archaeological Sites and Historic Buildings

Old Montreal contains many outstanding archaeological sites and historic buildings. Since the 1980s, archaeological digs in four city squares in Old Montreal (Place Royale, Place Jacques-Cartier, Place d’Armes and Champ-de-Mars) have led to numerous discoveries. More targeted archaeological campaigns have documented the presence of Indigenous people as well as European settlers. Saint-Éloi Street, for example, contains artifacts dating back 4000 years. Other sites bear witness to the transition of the St Lawrence Iroquoians to a sedentary lifestyle from the year 1000 to the end of the 16th century. Archaeologists have studied the sites of the founding of Montreal, the first Notre-Dame Basilica and the first Chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours, as well as several dwellings from colonial times. The city government has also overseen the marking of the traces of the old fortifications and the Château de Vaudreuil in order to make this little known and generally invisible heritage more tangible. Although most of the archaeological sites are not accessible to the public, the Pointe-à-Callière and Marguerite Bourgeoys museums, like the remains of the fortifications of Montreal at Champ-de-Mars, offer visitors some unique archaeological experiences.

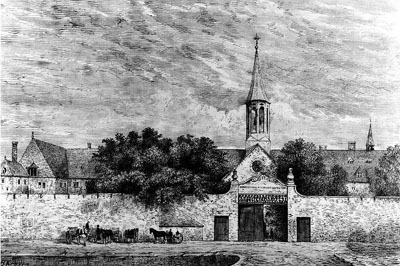

Old Montreal also contains many historic buildings. As the result of fires and ongoing urban change, many buildings from the New France period have been lost, and few traces of it can still be seen. It was the fear of seeing unique buildings continue to succumb to the wrecking ball that led the authorities to intervene in the early 1960s. As a result, a number of buildings still stand to bear witness to the fortified city and its expansion into the suburbs. These buildings include the Old Saint-Sulpice Seminary (1684-1687), the old Montreal General Hospital (1693), the Clément-Sabrevois de Bleury house (1747), the Brossard-Gauvin house (1750) and several other residential buildings.

The street grid and spatial organization of the built environment of Old Montreal are the legacy of the colonial period and the first centuries of urbanization, which specialists long considered the only important period of the district’s built heritage. But the importance and qualities of the district’s eclectic architecture (also known as Victorian architecture) are now recognized as well. Over the second half of the 19th century, the part of Old Montreal that lies west of St. Lawrence Boulevard underwent radical change. On Sainte-Hélène Street, ten buildings combining stores and warehouses were built between 1858 and 1871, and they remain magnificently preserved today. Saint-Jacques Street, known as the Wall Street of Canada, is another fine example of Old Montreal at the height of its economic splendour.

One square in particular, the Place d’Armes, neatly encapsulates the city’s evolution since its founding and the richness of its heritage today. At its centre, Montreal’s founders, Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve and Jeanne Mance, are commemorated by a monument and statues that were erected to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the city’s founding in 1892. On the south side of the square, the Saint-Sulpice Seminary and the Notre-Dame Basilica (1824–29) bear witness to the power of the Sulpicians, a society of priests who governed Montreal Island until 1854. To the north, the Bank of Montreal (1845–47) and many other banking edifices alongside it reflect the growth of Montreal’s finance industry in the 19th century. To the east, the New York Life Insurance Building (1887–89, Montreal’s first skyscraper) and the Aldred Building (1929–31, a 23-storey Art Deco affair) reveal the growing influence of the United States in the first half of the 20th century. To the west, the construction of the National Bank of Canada Building (1965–68) asserted French-speaking Quebecers’ place in the banking industry and introduced the international style to this part of Montreal. In short, the wealth of Old Montreal’s archaeological sites and historic buildings makes it a true showcase for the heritage of Montreal.

A Tourist District with Numerous Cultural and Recreational Attractions

In parallel with steps to protect the heritage of Old Montreal came its development as a tourist district. The year 1967 saw the Expo 67 exhibition, along with the celebrations of the 325th anniversary of Montreal’s founding and the centennial of Canadian Confederation, all of which gave impetus to historically oriented projects in Old Montreal. The restoration of buildings, the installation of old paving stones and 19th century style lampposts, along with controls on commercial signage, changed the appearance of the urban environment. A tourist information centre was opened on Notre-Dame Street, and walking tours were specially created to help visitors explore the wealth of heritage attractions. New museums opened to enhance the cultural offerings already available at the Château Ramezay (1895) the oldest history museum in the district. The openings of the Centre d’histoire de Montréal (1983), the Sir George-Étienne Cartier National Historic Site (1985), the Pointe-à-Callière Museum (1992) and the Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum (1998) further diversified the opportunities for tourists and Montrealers to enjoy interpretive experiences of the heritage of Old Montreal.

As the cultural offerings of Old Montreal grew, so did the temptation to turn the whole district into a kind of museum. In the 1960s, when some buildings along Bonsecours Street were threatened with demolition, history buffs talked about moving them to another site and creating the “Village of Maisonneuve”. In the 1970s, there was talk of reconstructing the old general hospital operated by the Grey Nuns. Neither of these projects was ever carried out, but tourism in Old Montreal continued to grow, stimulated by the ongoing development of heritage sites and attractive cultural offerings. Tourism pressure in Old Montreal reached a breaking point during the celebrations of the 350th anniversary of Montreal, in 1992. The day after the festivities, the various stakeholders in Old Montreal began discussing how to better balance a variety of urban priorities. As a result, after years of indecision, the Old Port of Montreal was converted into a space for recreation and tourism, helping to distribute visitors more widely across the city and relieve some of the pressure on Old Montreal. The conversion of more and more heritage buildings into charming hotels also distributed visitors’ presence across the entire day and made the neighbourhood more lively at night. So did Opération Lumière, a permanent lighting plan introduced in 1996 that showcases the architectural heritage of Old Montreal and enhances its ambience and safety at night. Thus, in a very natural way, the district’s architectural and historical attributes have become engines for the kinds of cultural and recreational projects that stimulate tourism.

A Place to Live and Work

In the 1960s, the objective of urban renewal in Old Montreal was to make it was to create a “living neighbourhood”. The municipal authorities wanted to eliminate industrial nuisances and reduce car and truck traffic. Business and commercial activities were thus changed gradually while older functions were maintained. A renewed emphasis on the district’s residential vocation was also deemed essential. Its housing stock had been in long decline since the late 19th century, and although a few pioneering souls renovated old buildings so that they could enjoy living in an historic district, its population continued to fall. As of 1976, only 555 people actually lived in Old Montreal. A laborious process of restoration was therefore undertaken.

Converting old buildings was a way of putting the area’s architectural heritage to residential use. One of the pioneering projects, The Cours Le Royer, was carried out from 1976 to 1982 and became a huge success. It involved redeveloping five former store-warehouses to create over 200 apartments. The conversions of the Cours Saint-Pierre, the C.P.R. Telegraph Building and the Lyman Building radically changed the area’s housing stock. Over the following decades, many more buildings were revitalized while new ones were built as well. The Faubourg Québec district to the east of Old Montreal and the Faubourg des Récollets district to its west offered development potential that the historic district could not. Consequently, the area’s population grew. As of 2016, nearly 3,500 people lived in Old Montreal (7,000 if these two districts to its east and west were included). The Association des résidants du Vieux Montréal (Old Montreal Residents’ Association) was established in 1993 to protect the quality of life in the district.

Enhancement of the heritage of Old Montreal has also led to some important economic changes. In the 1960s, there were still some remnants of the manufacturing, fur storage, chemical and pharmaceutical industries that had once been the mainstays of the district. But because these kinds of businesses no longer fit the profile of a historic district, a process of conversion began—dominated, unsurprisingly, by the tourism and cultural industries. Old Montreal now also has many businesses that provide professional, legal, scientific and technical services, drawn to the area not only by its heritage charms but also by the presence of the federal, provincial and municipal governments with which these businesses deal. As of 2016, 35,000 people were working in Old Montreal and helping to keep it a living neighbourhood.

Conclusion

Old Montreal is a gem at the very core of Quebec’s largest city, with a rich urban heritage that makes it unique in North America and attracts some 6.5 million visitors every year. Yet it is far more than just a tourist destination. It is a place where thousands of people live and many more thousands go to work every day. Not everything is perfect there, and the balance among the area’s various vocations is fragile. But there is no question that the heritage-development efforts that have been under way for nearly 60 years now have saved this district and helped to showcase the rich history of Montreal.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom