Petitioning is one of the most common tools of political protest accessible to the local population. Limited during the era of New France, the practice of collectively petitioning political authorities became much more frequent in the years following the Conquest by the British. Sanctioned in the 1689 Bill of Rights, petitioning had been a common practice in Britain for centuries, and ever since 1763, Canadians have been sending petitions to their governments (colonial, imperial, federal, provincial, and municipal) for a variety of reasons. With the recent introduction of e-petition, Canadians, more than ever, can have their voices heard in government.

Petitioning in New France

One of the most common tools of political protest, petitions provide a population with a medium to critique a decision taken (or not taken) by their government or demand the resolution of any situation that they find particularly troubling.

In Canada, during the French colonial period, petitioning was not commonly practiced, which is no surprise as collective petitioning was forbidden in absolutist France. Despite this inability to collectively appeal colonial authorities, historian Mathieu Fraser maintains that colonists nonetheless had a voice in the colony. While the Crown further centralized its authority in Europe, in the colonies, the situation was more flexible. For instance, Assemblies of Notables — though uncommon in France — were more frequently summoned in New France. These were used by local authorities to gain valuable insight into the opinions of the local population. Colonists could also send written requests — known as requêtes — to colonial officials to ask for specific favours or “obtain justice” from colonial authorities.

Petitioning after the British Conquest: 1763–1791

Petitioning became more frequent following the conquest of New France by the British. In fact, it had been a common practice in Britain for centuries — dating as far back as the reign of Edward I (1272–1307) — and had been an inalienable right for a century by the time of the Conquest. In 1689, the Bill of Rights sanctioned the practice into a right, stating: “it is the right of the subject to petition the King, and all commitments and prosecutions for such petitions are illegal.”

Along with a failed attempt to assimilate French-speaking colonists, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 also established British laws, customs and practices to the colony. Included amongst these was the ability to petition. English-speaking colonists that settled in the newly conquered colony took full advantage of this, a fact that did not escape popular historian Jacques Lacoursière, who described the period between 1784 and 1791 as “l’ère des pétitions.”

This “era of petitioning” coincided with the arrival of thousands of Loyalists in the wake of the American Revolution. Many were dismayed to find a British colony — the Province of Quebec — administered by French civil law. They were also frustrated that there was no elected assembly and used petitions to press for change. On 11 April 1785, for instance, Colonel Guy Johnson presented a petition to the King on behalf of John Johnson and a group of Loyalists. Seeking to escape the clutch of French civil law, the petitioners pleaded to turn a piece of land southwest of Montréal — near Lac Saint-François and Pointe Beaudet — into a separate colony with proper British laws and customs. In the decades that preceded the Constitutional Act of 1791, numerous petitions were sent to the Crown, some insisting for the establishment of an elected assembly even included signatures from French-speaking colonists.

Petitioning in Pre-Confederation Period: 1791-1867

Following the Constitutional Act of 1791, the Province of Quebec was divided into two — Upper and Lower Canada — and elected legislative assemblies were established in both colonies. As such, colonists were now able to directly petition their elected representatives.

In Lower Canada, colonists quickly adopted the practice. In fact, in the three years that followed the Constitutional Act, 43 petitions were submitted to the Legislative Assembly. Interestingly, the majority (60 per cent) followed the 1792 election, which suggests that colonists used petitions to contest electoral results. According to historian Steven Watt, this practice continued well into the 19th century. Furthermore, the majority were produced by collectives and tackled a variety of concerns. For instance, while some demanded that authorities fund the construction of a local bridge or road, others pleaded for the establishment of a court in their town. It appears, however, that these petitions had very little impact on the legislative process. Only seven out of the 43 petitions were not rejected outright.

Initially, very few petitions pushed for political reform. However, this changed in the period leading to the Canadian Rebellion. According to Watt, petitioning not only became much more frequent during this period — over 800 petitions were sent to the Governor General, the Legislative Council, and the Legislative Assembly between 1820 and 1838 – but Lower Canadians began using them as a “tool for political expression.” Though settlers continued to send petitions for numerous reasons, Watt believes that these hint at a much larger political ideology. For instance, though petitions focusing on road conditions, or the state of local education, or the “management of natural resources” do not appear to have any political implication on the surface, Watt argued that colonists were indeed voicing their political opinions, pushing their elected leaders to “focus on local needs.”

Upper Canadians also took to petitioning, quite a lot more than Lower Canadians. Between 1815 and 1840, over 6,800 petitions were sent to the lieutenant-governor and the majority were on a specific topic: land grants. In the wake of the American Revolution, the arrival of Loyalist refugees and the creation of Upper Canada in 1791, newcomers were given free land to settle in the new colony. However, in order to obtain this free land, settlers had to petition colonial authorities. In the decades that followed, from 1783 to 1841, Loyalists that suffered as a result of the American Revolution, military personnel and later the children of Loyalists petitioned for land. Upper Canadians also petitioned for jobs. These usually came from affluent individuals seeking a position in the colonial administration. Finally, petitions to pardon a loved one from a crime were very common. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these were very common in the years following the Rebellion.

In the late 1840s, both Tories and Reformers in Canada East and West produced petitions on the Rebellions Losses Bill,

a bill that compensated Lower Canadians for the property damage (and other losses) they suffered during the Rebellion. While Reformers supported the bill as an important step towards the restoration of friendly relations following the events of 1837

and 1838, Tory petitions, some addressed directly the Queen, condemned the bill for rewarding, with financial compensation, disloyalty. According to Alain Roy, Tories produce 34 petitions, including 7 from Canada East, in the weeks following the introduction

of the bill at the Legislative Assembly.

Who was petitioning before Confederation?

According to Steven Watt, the majority of petitions were from adult males of European descent, revealing the privileged position they had in society. White men, regardless of their class, could petition; these came from the educated, illiterate, poor, wealthy, Loyalist and Reformers. According to historian J.K. Johnson, “even illiteracy was not an insuperable barrier since petitions often came from people who could not sign their names.”

The case of Indigenous peoples is complex. Though some have suggested that they did not petition colonial authorities as they were “largely denied the formal rights of political citizenship,” research conducted by historian Maxime Gohier suggests that those residing in the St. Lawrence River Valley did adopt the practice. In the wake of the 1791 Constitutional Act, Indigenous peoples that sought to entertain a diplomatic relationship with colonial authorities were advised to do so through petitions (see Indigenous-British Relations Pre-Confederation; Indigenous People and Government Policy in Canada). And with the assistance of notaries or missionaries, they did. Petitions sent in the name of Indigenous peoples were very similar to the ones prepared by settlers, but with one major exception: Indigenous people were often treated like “children”, with their poverty and dependence on the government frequently emphasized. This had a very negative impact as it gave the British government the impression that Indigenous peoples were “naïve” or unable to care for themselves, legitimizing their authority over them. It was the duty of the mother country to “protect” them. Despite the above, Gohier maintains that these petitions did allow Indigenous peoples to integrate the Canadian political process and affirm a “distinct political identity.” They legitimized the authority of Indigenous leaders and their role as the representative of their people, and provided the theatre to push for Indigenous rights.

Black people in British North America also petitioned. For instance, a group of Maroons that were deported from Jamaica to Nova Scotia in 1796 petitioned authorities for passage to a warmer climate. They even sent petitions to London pleading their case. Four years after their arrival, in August 1800, they finally got their way; the Maroons left Nova Scotia for their new home in Sierra Leone. Likewise, in Upper Canada, Richard Pierpoint, a former slave who settled in the colony after the American Revolution, also petitioned colonial authorities. In 1794, he and 18 other Black settlers sent a petition to John Graves Simcoe, pleading that they be allowed to settle land that was next to one another and was also isolated from white communities. They also asked to settle an area that was isolated from white communities. Though the petition was rejected, Pierpoint continued to petition colonial authorities; first, during the War of 1812 for the creation of an “all-Black militia” and then following the war for passage to his native West Africa ( see The Coloured Corps: Black Canadians and the War of 1812).

Petitioning in the Late 19th and the Early 20th Century

In the years that followed Confederation, petitions continued to be an important tool for change as newcomers and marginalized populations used them to push for rights or to protest unfair treatment.

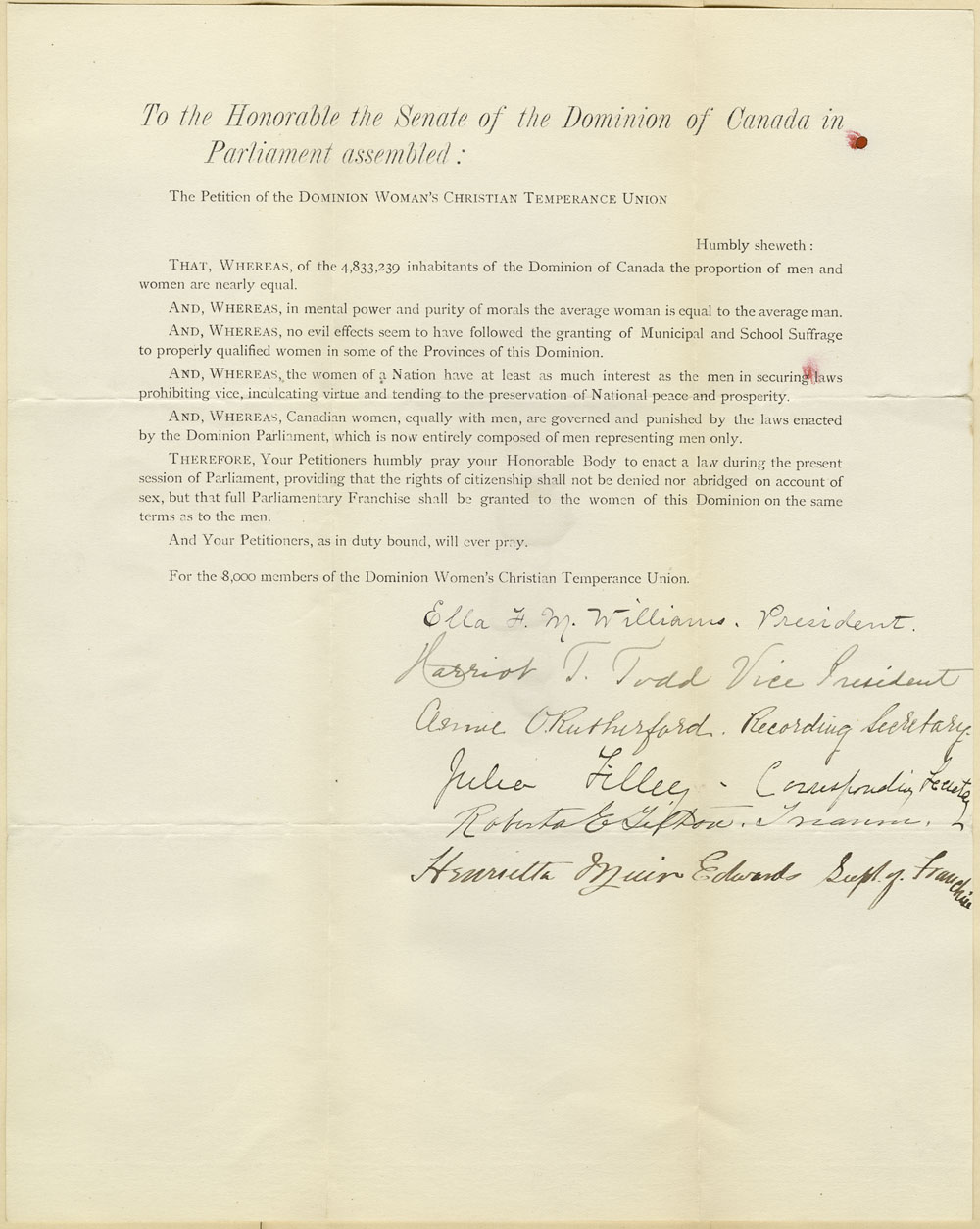

Starting in the 1880s, women in Manitoba would walk “countless miles” to collect signatures and gain support for their right to vote (see Women’s Suffrage in Canada). For instance, Dr. Amelia Yeomans collected over 5,000 signatures. Though their demands were rejected by provincial authorities, in the next three decades — and until 1916, when they finally gained the right to vote — women in Manitoba continued to use petitions to pressure the provincial government. One of the most important petitions came from the Political Equality League, who in 1913 sent a petition of over 20,000 signatures to the Manitoba Liberals. Later in 1915, after Premier Tobias Norris vowed that he would grant women the right to vote if the Political Equality League submitted a petition of 17,000 signatures, they presented him with a petition of 39,584 names.

Chinese immigrants also used petitions to protest unfair laws and regulations, such as the Chinese Head Tax (1885) and the Chinese Immigration Act (1923), which subsequently first limited and then banned Chinese immigration into Canada. In 1894, Chinese immigrants living in Victoria, British Columbia also petitioned the federal government, asking to extend “the time for a Chinese person leaving Canada to return within eighteen months instead of six months the time therein limited.”

However, petitions were also used for unjust and discriminatory causes (see Prejudices and Discrimination). At the turn of the 20th century, many Canadians feared the arrival of Black immigrants and many petitioned the government to ban Black immigration into Canada. In 1911, for instance, a petition circulated in Edmonton arguing that “[i]t is a matter of common knowledge that it has been proved in the United States that negroes and whites cannot live in proximity without occurrence of revolting lawlessness, and the development of bitter race hatred.” This petition amassed thousands of signatures and, along with intense public pressure, it led to the passage of Order-in-Council PC 1911-1324, which banned “any immigrants belonging to the Negro race, which is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.”

Petitioning in the 21st Century

Today, Canadians have the ability to petition their municipal, federal, and provincial governments. Throughout the course of the 20th century, however, federal and provincial authorities restructured petitioning, adding a specific set of guidelines that each had to follow to be deemed admissible. The aim was to make petitions more unified and standardized in order to streamline and facilitate the review process. This was especially the case at the federal level, starting in the mid-1980s, when the Government of Canada observed a “resurgence in the use of petitions.”

How to Petition the Canadian Government?

In order to be deemed admissible — and ultimately forwarded to the House of Commons — Canadians must take a number of things into account. First, every petition has to be respectful in tone (any petition considered disrespectful will be rejected). Petitions must be addressed to the House of Commons, not to the Prime Minister nor a specific minister or member of Parliament. The “prayer” — or the action the petitioners hope the government will take — follows.

Petitioners must be certain that their demand falls within the jurisdiction of the House of Commons as the House of Commons will not discuss matters that are considered the jurisdiction of municipal or provincial governments. Petitions requesting public funds — to redress a hardship, for instance — have also been frequently rejected by the federal government. However, petitions asking for “the enactment of a measure” to resolve said hardship will be accepted. Each petition must also be free of erasures, interlineations, and must be written, typewritten or printed, and each must contain the signatures and permanent addresses of 25 individuals. Finally, although petitions coming from exclusively non-resident aliens will be rejected, petitions signed by Canadians as well as non-resident aliens will be accepted. If deemed admissible, a maximum of 15 minutes will be given to the presentation of each petition “during the daily routine of business.”

E-Petition in Canada

With the recent addition of e-petition, Canadians, more than ever, can have their voices heard in Parliament. Since December 2015, Canadian citizens have the ability to send petitions to the House of Commons via a new online system. Previously, petitions created on websites like change.org were not considered “official” and as a result inadmissible for review at the House of Commons. Canadians have jumped on this opportunity. Accordingly, in the first three months following the launch of the website, over 40 petitions were created on the website, including well over 100,000 signatures. Similar to traditional petitions, a similar set of guidelines must be followed. Most important, in order to be considered, each petition must be sponsored by a member of Parliament and only those that receive over 500 signatures will be tabled and presented to the House of Commons. Once presented, the government will have 45 days to officially respond to the petition. Change is at the click of a button.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom