Pullman Sleeper Cars

George M. Pullman invented the Pullman sleeper car in partnership with Benjamin Field. Designed for overnight travel, Pullman sleeper cars were first used in the United States in 1865 and introduced in Canada by the 1870s. Pullman cars were more comfortable and luxurious than regular passenger cars, with chandeliers, privacy curtains and silk shades, vibrant colours, dark walnut panelling and richly upholstered seating. At night, seats were unfolded as beds and bunks were pulled down from the wall.

After initial success in the United States, the use of sleeping cars grew rapidly in Canada. William Van Horne, general manager and president of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), tripled the CPR’s investment in sleeping cars between 1885 and 1895. Other Canadian railways, such as the Canada Atlantic Railway and the Intercolonial Railway, also increased the number of sleeping cars in their fleets.

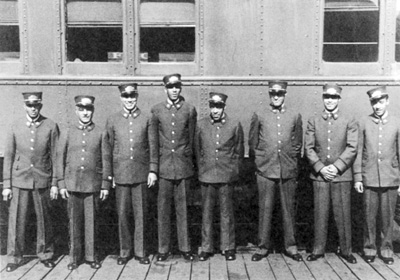

Black Railway Porters in Canada

One reason why sleeper cars were so successful was the high level of service provided by porters. In both the United States and Canada, Black men were preferred hires because of their history in domestic service. The American Civil War, which ended in 1865, freed thousands of enslaved Black people, many of whom needed jobs. George Pullman modelled his train service on enslavement-era servitude and hired Black men to work as porters for his company. (By the 1920s, Pullman was the largest employer of Black men in the United States.) When sleeper cars were imported to Canada, Pullman’s service model came along with it.

In Canada, porters were hired from cities with established Black communities, including Africville in Halifax, Little Burgundy in Montreal and Toronto’s Bathurst and Bloor area. According to historian Sarah-Jane (Saje) Mathieu, “Many African Canadians migrated westward for promotions or better opportunities with the Pullman Palace Car Company, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and the Grand Trunk Railways.” As a result, 76 men were working as porters out of Winnipeg by 1909. As well, Black settlement in Vancouver’s Hogan’s Alley, was largely due to the neighbourhood’s proximity to the Great Northern Railway station, where many of the men in the community worked as porters.

Porters were also recruited from the southern United States and as far as the Caribbean. At the time, Black immigrants were often denied entry to Canada through loopholes in immigration law (see also Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324 — the Proposed Ban on Black Immigration to Canada). However, CPR agents are reported to have told Black recruits from the United States and the Caribbean to present CPR business cards to Canadian border guards, who would allow them passage. Between 1916 and 1919, more than 500 Black porters arrived in Canada to work for the CPR.

Black men found relatively steady and consistent income working as railway porters, one of few opportunities available to them. Many of the Black men who found work as porters were highly educated, but because of racism and discriminatory hiring policies could not get jobs in their respective fields. Instead, they had to settle as railway porters just to receive a steady, albeit low, income.

The Road Taken, Selwyn Jacob, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Labour Struggles

Though the position carried respect and prestige for Black men in their communities, the job came with many difficulties and limitations. Porters were expected to work long hours, sleeping for only a few hours a night, often in the men’s smoking room on the train. They were on call for 24 hours and were away from home for many days at a time. As well, harsh discipline from management, low pay and lack of job security were common. Since few opportunities were available to Black men at the time, employers were able to exploit Black porters knowing that if a person quit over poor working conditions, a replacement could be easily hired.

DID YOU KNOW?

Senator Calvin Ruck worked as a sleeping car porter with the Canadian National Railways. He later said that experiencing racism as a porter was a political awakening. “I felt obliged to protest,” he later said. But organizing at the time seemed impossible. “We were afraid to rock the boat. We thought we might end up with no job at all.”

Black porters faced racism in every aspect of their job. For example, passengers regularly disrespected porters by calling them demeaning names like “George” (as in George Pullman) or “boy.” As well, Black porters received lower pay than their White colleagues, did not receive promotions and could not apply for higher positions (such as engineer or conductor).

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

Black railway employees were prevented from joining the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (CBRE), the most powerful railway union at the time. The CBRE’s constitution, drafted in 1908, said that only White people could be members.

In April 1917, Black porters based in Winnipeg — John A. Robinson, J.W. Barber, B.F. Jones and P. White — formed the Order of Sleeping Car Porters (OSCP), the first black railway union in North America. Within two years, the OSCP had negotiated contracts for sleeping car porters on the Canadian Northern Railway and the Grand Trunk Railway. In 1919, the union joined the CBRE, which agreed to remove the “Whites-only” clause from its constitution. However, Black members were given segregated membership for lower-paid positions. Four Black locals of the CBRE were established.

DID YOU KNOW?

In August 1925, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was established by Black railway workers in the United States. This labour union was led by Asa Philip Randolph and Milton P. Webster and sought fair and equal treatment for Black workers on the rails.

By 1939, the Canadian porters were given membership in the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters — an American union. The Canadian chapter worked alongside its American counterpart to fight against racism and the various challenges that Black porters faced on the job. Over the next few years, porters across Canada organized in secret so that they wouldn’t lose their jobs. In 1942, Canadian porters formed BSCP divisions in Montreal, Toronto and Winnipeg and later in Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver. Porters voted to unionize; however, a collective bargaining agreement was not signed with the CPR until May 1945.

DID YOU KNOW?

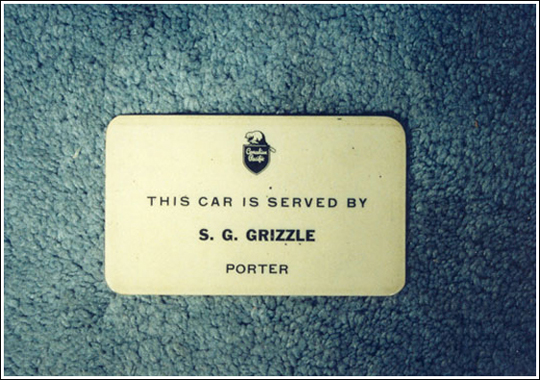

Stanley G. Grizzle was the first Black Canadian citizenship judge. For 20 years before that, Grizzle worked as a porter. In that time, he also advocated and negotiated better working conditions for porters and was elected president of the Toronto CPR division of the BSCP in 1946. His memoir, My Name’s Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada, Personal Reminiscences of Stanley G. Grizzle, was published in 1998.

Some of the changes and benefits that were made as a result of the new collective agreement included monthly salary increases, one week’s paid vacation and overtime pay. As well, porters gained the right to put up plaques in sleeping cars that clearly stated their name. The union also helped negotiate for better working and sleeping conditions while on the job, and fairer and more transparent disciplinary measures.

Although the collective agreement between porters and the CPR was significant and helped change some things for Black porters, they still had to fight and struggle against racism, discrimination and disrespect while on the job. Porters were still discriminated against when applying for roles such as conductor, a role that was historically reserved for White men. The BSCP took up this cause and in 1953, filed a complaint with the federal Department of Labour, under the Canada Fair Employment Act of 1953. In 1954, one of the claimants in the case, George V. Garraway, was hired as the first Black Canadian train conductor.

DID YOU KNOW?

Rufus Rockhead was a sleeping car porter for the Canadian Pacific Railway who financed his famous Montreal jazz club, Rockhead’s Paradise, with money earned as a porter. Established in 1928, Rockhead’s Paradise hosted such American jazz greats as Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Lead Belly, Nina Simone, Fats Waller, Dizzy Gillespie and Sammy Davis Jr. It also helped launch the careers of local talents such as Oscar Peterson, Oliver Jones and Billy Georgette.

Significance and Legacy

Beginning in the 1960s, changes in the travel industry caused railways to employ fewer sleeping car porters; however, the impact that the BSCP made within Canadian history is profound. At a time when Black people were fighting for their basic human rights, the BSCP was a much-needed group that helped to fight for the rights of Black men in the workplace. Canadians such as Stanley G. Grizzle, Donald W. Moore and Harry Gairey, who were porters early in their careers, helped in the fight for equality and better working conditions and pay for porters. With plaques commemorating and honouring the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in downtown Toronto and at Windsor station in Montreal, the profound impact that this group made and what they were able to accomplish is forever cemented in Canadian history.

This episode looks at early Caribbean migration to Canada and reveal which islands could have become Canadian provinces. Leah and Falen also dive into the history of Black railway porters and how they and their wives made Winnipeg a hub of labour activism in Canada.Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom