Wartime Epiphany

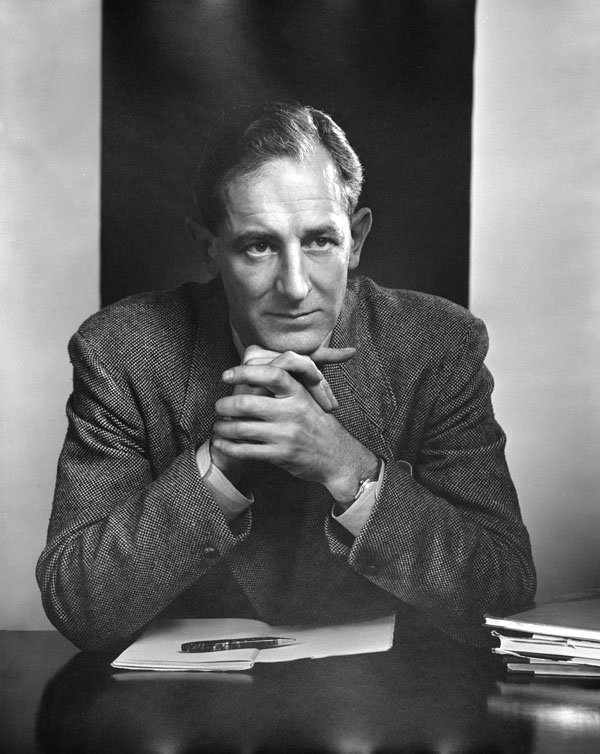

Farley Mowat went to war in 1942, like many of his young mates, brimming with confidence, bravado and patriotism. Two years later he was a changed man — still loyal to the honour of his army regiment — but broken in spirit by what he had seen.

"The Second World War was the single most important element in my existence," he said in 2005, at age 84. "It was a turnaround point in my life. It gave me clarity that I otherwise might never have acquired.

"I saw my own species behaving in a way that no other living creature would ever duplicate. It made me consider that perhaps we weren't the greatest form of life on Earth, not the absolute work of God, but perhaps some kind of cosmic joke, and a rather devilish one at that."

Mowat came home from the war, not celebrating the Allied victory, but seeking an escape from a modern society that for him was now a symbol of death and shame. His searching took him to the inland Inuit of the

The books that would make him famous — Lost in the Barrens, Coppermine Journey, Never Cry Wolf, for example — would not have been written, he says, if not for his wartime epiphany and his new-found pessimism in humanity.

Sixty years later his views haven't changed.

"I don't have much regard for my own kind," he says. "I don't think it will matter a damn, in the last analysis, if we vanish from the planet. In fact there is reason to think it would be a good idea if we did. It would give other forms of life a better chance."

Fighting in Italy

The son of a First World War veteran, Mowat grew up around the shores of

"The Sicilian campaign was an exhilarating if exhausting experience," Mowat has written. "But horror at what we were engaged in quickly began to build within us ... by the time

Mowat spent many months in combat, slogging his way with the rest of the Canadians slowly northward through

Even on leave from the front, there was no escape from the violence. Mowat's train, snaking along the Mediterranean coast one day toward a rest station in southern

By January 1944, Mowat was the sole surviving officer in his regiment among those who had landed alongside him in the assault wave on

His father, having known friends in the First World War who willingly walked in front of enemy bullets to escape the madness around them, fretted about his son's emotions and encouraged him, in letters to

Dogs of War

Today Mowat's views on remembrance are uncompromising and controversial: he eschews what he calls the glorification of war in many Remembrance Day events and military anniversaries. He says the media have elevated war into an act of heroism and prestige.

He also says he won't feel neglected if nobody remembers his own personal wartime service. "I escaped alive with my skin, and that's reward enough." What matters is to remember war, he says, "as the abomination that it is."

Stark and simple, Mowat's feelings are summed up in a letter he sent home from

"Tell him from me," he said, "the Dogs of War aren't what they're cracked up to be."

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom