Kaye Kaminishi is the last surviving member of the Vancouver Asahi, a Japanese Canadian baseball club. The team was disbanded in 1942, when the Canadian government interned 21,000 Japanese Canadians during the Second World War, including every member of the Asahi.

This is Kaye’s story.

What people love most is a tragedy with a happy ending

There’s a book called A Tragedy of Democracy about the history of Japanese internment in Canada. It’s written by a historian named Greg Robinson, who is a professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal. Professor Robinson concludes the book with this really interesting quote.

SAM FENN (narrator): Do you remember that off by heart?

GREG ROBINSON: Yes. It’s William Dean Howells, the famous novelist and American social critic, who said what Americans love most is a tragedy with a happy ending.

SF: What did you take that to mean when you first read it?

GR: That means that Americans feel deeply about things — and Canadians the same — but that they like their stories wrapped up neatly. And if you think that things work well in the end, that people will be able to understand them better.

We want tragedies with happy endings. Like a classic sports movie where the underdog faces adversity but then they win it all with a walk-off home run. In real life, things rarely work out that way.

SAM FENN: I need to be kind of close. Is this okay, like this?

KAYE KAMINISHI: Oh yeah sure.

SF: Kaye, can I have you introduce yourself?

KAYE: My name Kaye Koishi Kaminishi and I was born in Vancouver, 1922, January 11th.

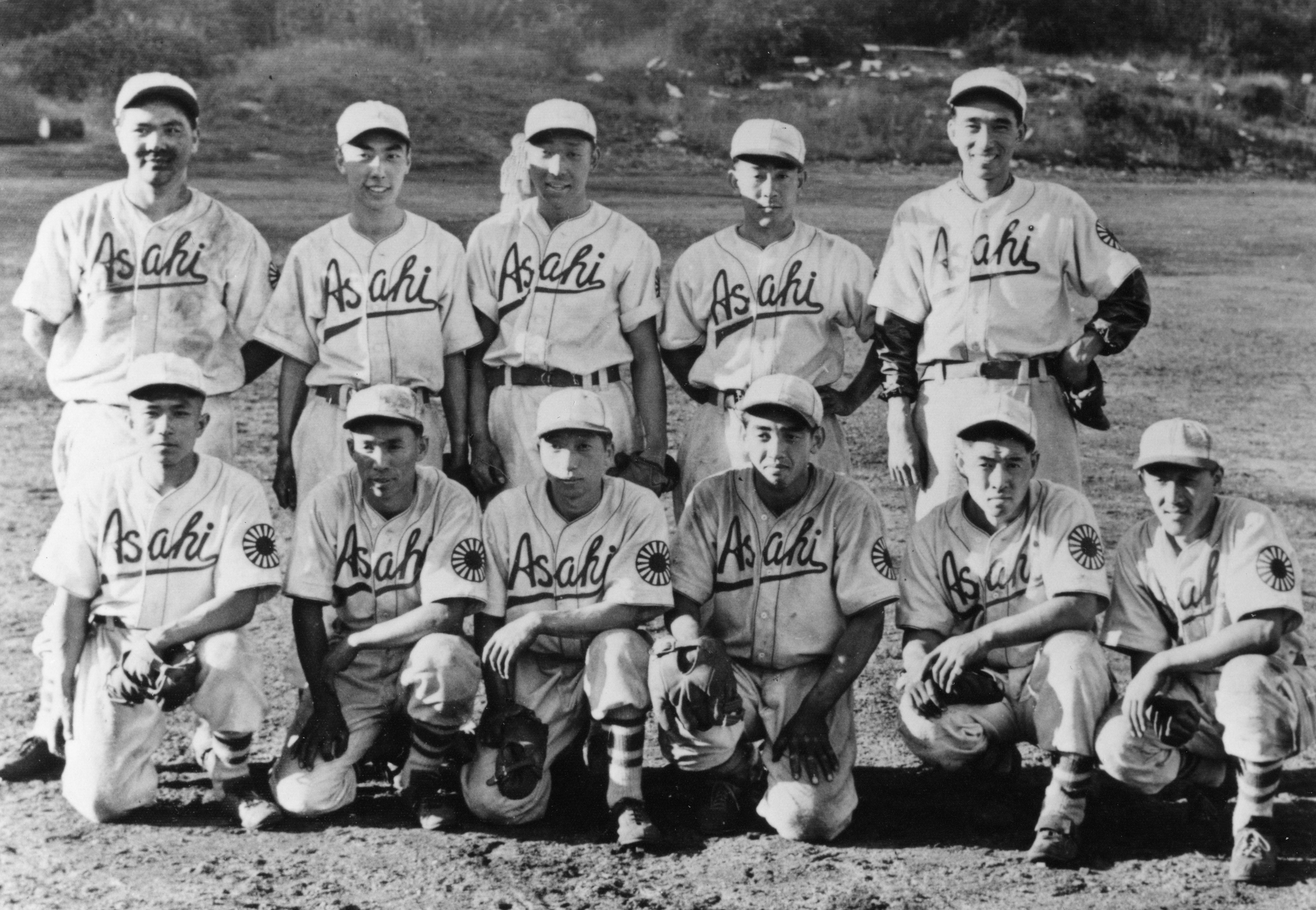

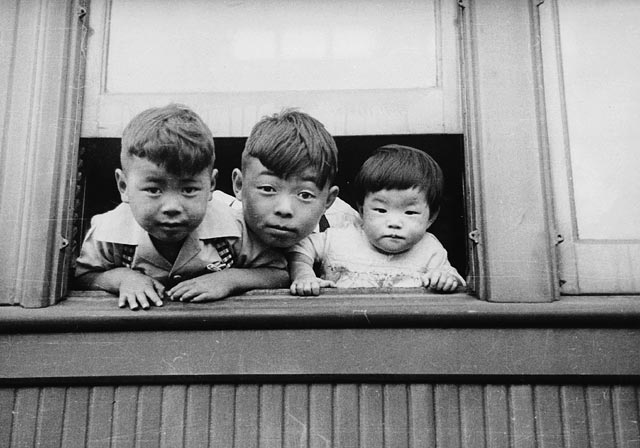

Kaye is 94 years old. He’s friendly. Delicate looking. In the 1920s and 30s, when Kaye was a kid, he lived right across the street from a ballpark called the Powell Street Grounds. This is home to Kaye’s heroes, an amateur baseball team called the Vancouver Asahi.

KAYE: Asahi plays, you know, some weeknights or Sundays… I go right away to watch. You know? Every Asahi game, I never missed it. Yeah.

SF: Were there quite big crowds for those games?

KAYE: You bet there were. Oh, when Asahi plays Japanese Town is empty.

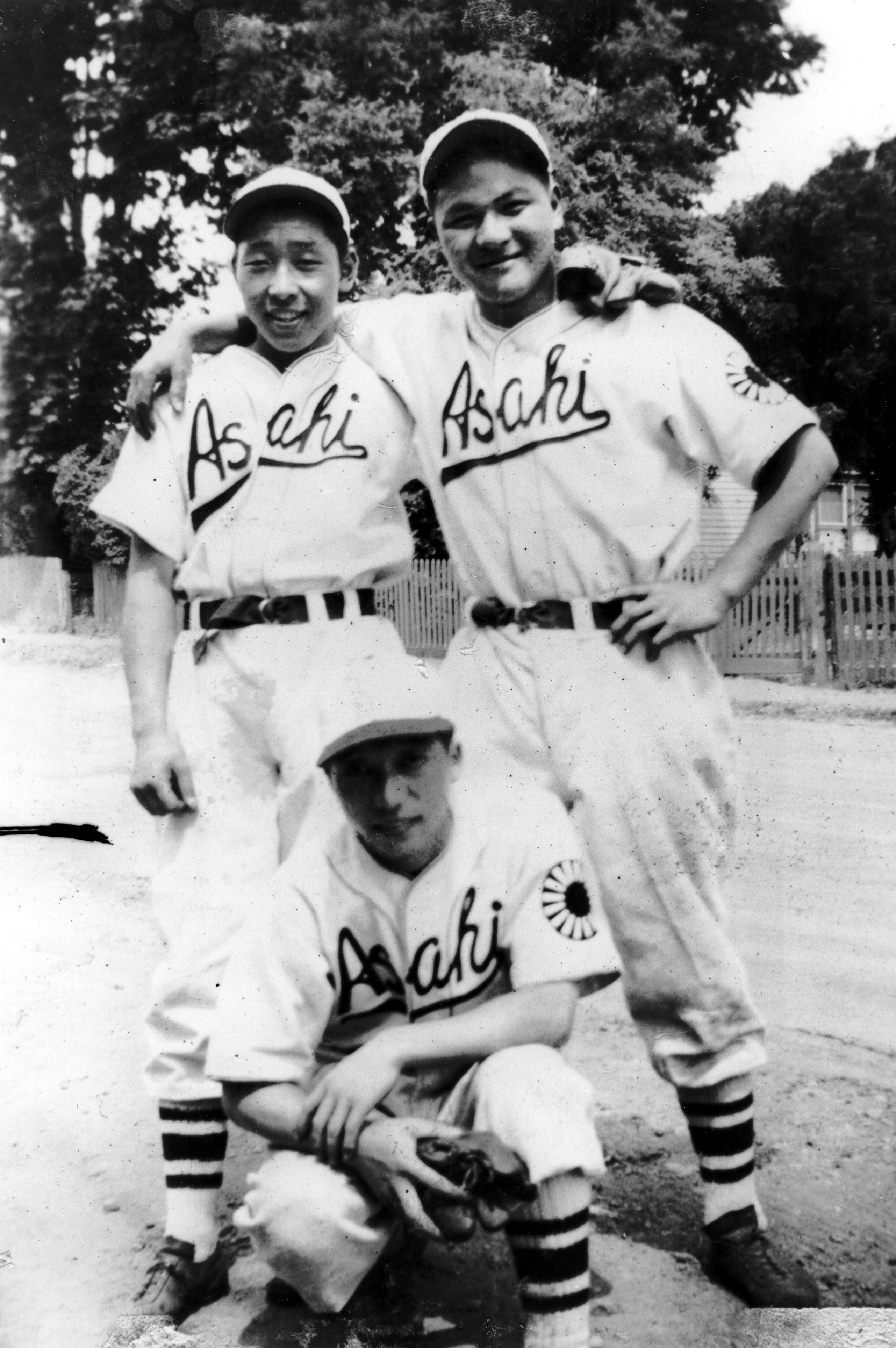

Picture a white jersey, a red sun on the sleeve and the word Asahi swooped across the chest. This team is entirely Japanese Canadian, and when the Asahi first start to play against white teams, they’re reviled. People shout slurs at the team from the field, the stands and the press box. But by the 1930s, the Asahi are the most popular team in the city. Kaye remembers Japanese people and white people watching the games.

KAYE: You know there’s only, like, the grandstand accommodates maybe 200 people. That’s about it, eh? So everybody right up on all the four corners of the street. Six deep. So, you know, a good two, three thousand people were watching the game — every game at that time.

KAYE: Of course Powell Street — Japanese town — was really quite a town. You’ve got everything up there. So you don’t have to go outside of Powell Street to go shopping or do anything.

Kaye’s father owns a profitable sawmill. His mother runs a boarding house. The Kaminishis are a wealthy family in a poor but vibrant part of town.

SF: What’s your earliest memory of baseball?

KAYE: I was in the school baseball club, and wasn’t real good team, but we used to go [to] school-to-school tournament quite often.

SF: They called you the vacuum cleaner, is that right?

KAYE: [Laughs] Yeah well, that’s uh… I usually don’t miss. That’s why they give me a nickname for a while, you know.

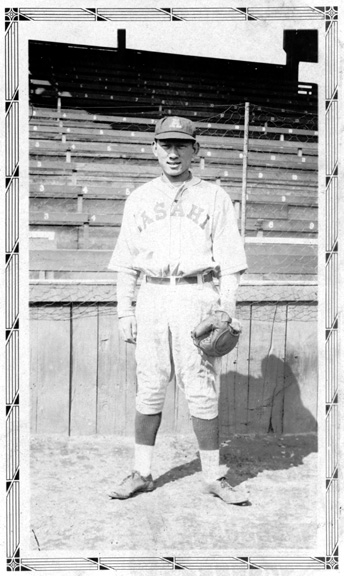

Kaye plays third base. He’s quick and sure-handed. He goes to school in Japan as a child and plays in a school league — then in a church league in Vancouver. And finally, in 1939, when Kaye is 17 years old, the Vancouver Asahi make an announcement.

KAYE: They pick up five rookies, and I was one of the rookies.

SF: Was it important to you to get picked up by Asahi? Was that something you wanted?

KAYE: Oh, that’s a proud moment, you know. If you get into the Asahi team and put the uniform on — oh, everybody thought you were king or something, you know? Real happy time. Yeah. Except I was nervous for a while, you know.

SF: What were you nervous about?

KAYE: Because, we were representing the Japanese community. So you know, if you miss something there’s not good rumours coming up, you see? So, you gotta be careful, you know?

You gotta be careful because there’s a spotlight on you. If you miss a groundball it might reflect poorly on the whole community. The Asahi are a real dynasty by the time Kaye makes the team. They had won a Japanese Baseball Championship in back-to-back years. But the Asahi don’t look like a good team. At this time, the best baseball player in the world is a six-foot-two slugger named Joe DiMaggio.

Many of Vancouver’s white players are the off-brand version of DiMaggio. They’re big, burly guys who aren’t so fast but are strong enough to hit home runs. The Asahi are different.

KAYE: We were kind of small. We can’t hit too many homers or big hits. So only thing we have to win is stealing bases, and bunts, and squeeze play.

The Vancouver press call this brainball. It’s really all about bunting. Imagine you’re standing in the batter’s box, and the pitcher throws the ball to the plate. Instead of swinging as hard as you can, you just sort of stick the bat out. The ball bounces across the infield. If you do it right, it will take the fielders just a little too long to pick it up and throw you out.

SF: Do you know who was the best bunter on the team?

KAYE: Well, actually, everybody good bunter.

SF: Were you quite good?

KAYE: Oh, I was quite good. Yeah.

Kaye spends most of his first season riding the bench as the team wins the Pacific Northwest Championship. He’s a proud benchwarmer, honoured just to be on such a talented team. At only 17, his best playing years are all ahead of him.

Internment

SAM FENN: We hear that Vancouver was quite a racist place at this time. Was that true in your experience?

KAYE KAMINISHI: Yes. You know, uh, people graduate university [and] can’t get no government job, no engineering jobs. And no voting rights. If you work in a place, you only get half the wages. So our parents really have a tough time.

SF: Japanese people can’t vote in BC. They can’t sit with white people at the movie theatres. And, for the most part, they live in racially segregated enclaves.

GREG ROBINSON: Uh, you know. It’s not called British Columbia for nothing.

SF: This is Greg Robinson again. He studies the history of Japanese Canadians.

GR: There’s a kind of rawness to the racism that you don’t get in the East. There are all of these whites that have gone all of this way to settle this new land — take it from the First Nations and from the Black settlers and the others who have been there before. And they want to build a white man’s country.

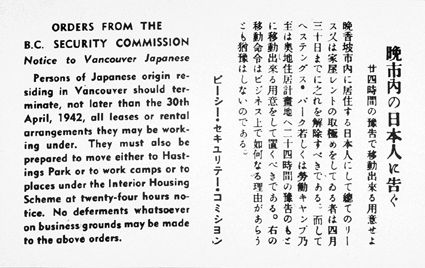

Kaye’s second season is set against an ominous backdrop. In 1940, Japan allies with Nazi Germany. White Vancouverites worry that their Japanese neighbours will be loyal to Japan, not Canada. So Prime Minister Mackenzie King takes action. He requires that Japanese nationals and Japanese Canadians register with the government. Everyone over 16 is fingerprinted, photographed and required to carry a registration card.

GR: I think that there was no special reason to suspect Japanese disloyalty. The buildup of racism, the buildup of suspicion, had very little to do with the facts on the ground.

ARCHIVAL CLIP: We interrupt this program to bring you a special news bulletin. The Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbour, Hawaii, by air, President Roosevelt has just announced. The attack also was made on all naval and military activities on the principal island of Oahu. We take you now to Washington. The details are not available...

SF: Do you remember that day?

KAYE: I can’t even remember, you know. I heard that, you know, Pearl Harbor bombing on the radio. That was so… not scared… but you know, we don’t know what’s going to happen. I can think anything, you know? Whole lot of rumours going on, you know. They come and pick you up, and you know… and uh, curfews and so on.

ARCHIVAL CLIP: A Japanese attack upon Pearl Harbour naturally would mean war. Such an attack would naturally bring a counter attack.

GR: I’ve heard various people’s stories about the word filtering through of the attacks. Some people got word as they were leaving church. Some people heard it on the radio while they were at home. A lot of people I know went home and were wondering what this is going to mean. And also were, I think, taken over by a mixture of emotions: shame, anger at Japan, worry for their loved ones.

ARCHIVAL CLIP: ... Their appearance at the State Department on this Sunday afternoon emphasizes the gravity of the Far Eastern situation, where hostilities now seem to be actually opening over the whole South Pacific.

On 23 February 1942, Mackenzie King signs order-in-council 1486. The government of Canada now considers everyone of Japanese ancestry an enemy alien. It doesn’t matter if you’re a citizen, if you fought for Canada in the First World War, or if you are a star baseball player: you’re the enemy. You have to evacuate the west coast.

KAYE: We have to get away from Vancouver: 100-mile radius. Gotta go out. I was hiding two months in my mom’s rooming house, eh.

SF: When you say you were hiding inside, do you mean you didn’t leave the house?

KAYE: That’s for sure. I couldn’t leave it. You don’t know who is, you know, detective or police or I don’t know. Meantime, if I get caught by RCMP I have to go to Ontario — prisoner’s camp up there.

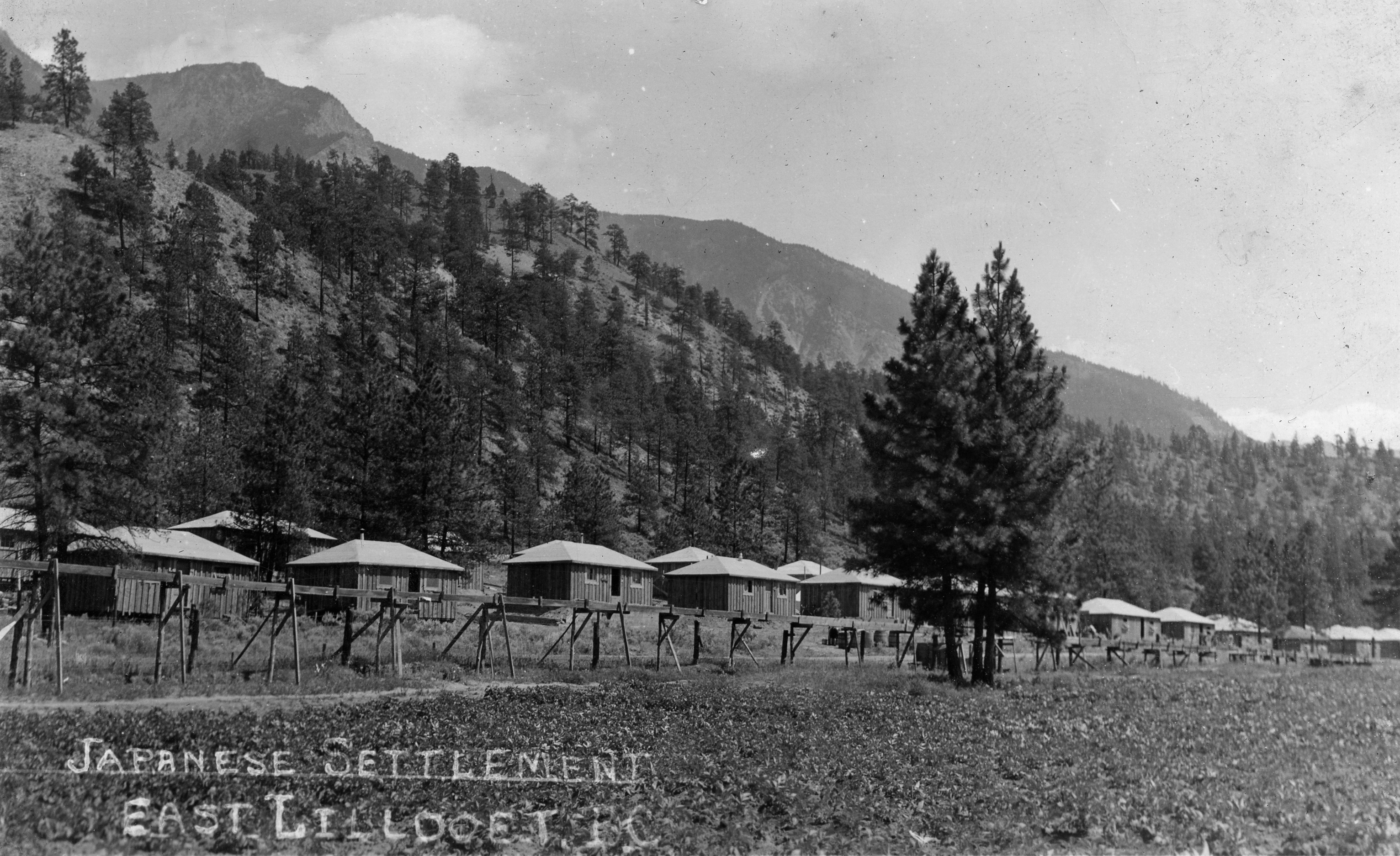

Eventually Kaye and his mom flee to a small town in northern BC called Lillooet. It’s a small Japanese collective overseen by the RCMP [and called East Lillooet]. The government calls this a “self-supporting community” because Japanese Canadians are required to buy their own land. When Kaye arrives, it’s a completely different world.

KAYE: Living in Vancouver, you’ve got everything. But up there… nothing there. Nothing there! No electricity. No water. We all get the buckets and go down to Fraser River, you know. Water just so muddy. Yellow, you know. So — really tough time.

When Kaye says there’s nothing there, he means nothing. It’s just a plot of dirt at the foot of a mountain. Just imagine that for a second: imagine your government passes a law forcing you to leave your city. You have to lease land somewhere else. You have to build a new house. And you have to fetch the dirty yellow water. And the most insulting thing is that there’s a bridge at the edge of the East Lillooet, and on the other side of the bridge is a proper town with grocery stores, a theatre, running water.

KAYE: We can’t go across the bridge to go to shopping or anything. Store keepers come get the order and they bring us next day you know… things like that… you know...

SF: So it’s like paying to be in a kind of prison?

KAYE: Yeah, yeah, yeah. That’s right.

In 1943, the government starts to sell the property it confiscated from Japanese Canadians. This includes the Kaminishi sawmill, which is supposed to be Kaye’s inheritance.

KAYE: See, my dad start 1917, you know? So we had quite a big business up there. Custodian took over [and] sold for little over $200,000. You know… And this fellow sold next year for $1,000,000. Million dollars! What a difference between only one years!

SF: It’s not fair.

KAYE: Really not fair. You know, they call us enemies anyway first of all. Why is that? We were born in Canada and we don’t do anything. I was getting mad for a while. All the people said, “Well, it’s a war. That’s why can’t help it.” You know, but to me, I was born in Canada and went to a Canadian school. Why our government do things like that?

Kaye is in his early 20s. And he’s stuck on the wrong side of the bridge with no end to the war in sight. He misses his home and friends — and he misses baseball. So he decides to teach the kids in East Lillooet how to play. It’s a way to pass the time, and the RCMP seem to like watching them run drills. One day Kaye talks to one of the officers.

KAYE: And this policeman was a real sportsman. So I tell him that we have a softball team and, “Why don’t you guys make one in town, eh? Let’s play each other, you know?” “Oh,” he says. “That’s a really good idea.” So he made one team in town. I told him, “Let us go one time to play the game up there. And you guys come east side next week.” You know, things like that. “Let’s go back and forth, you know.” We start doing this. Going back and forth.

SF: That was the first time you crossed the bridge?

KAYE: That was the first time crossed the bridge with the half-ton truck. You know, go to town.

SF: How did it feel?

KAYE: It felt really — oh! Now freedom comes, you know. That’s the reason town people start trusting us. And we could go to town and shop. There’s the one theatre there, you see. We used to go watch the show on Friday night and so on, you know.

SF: So you desegregated Lillooet!

KAYE: Yeah, sort of you know. Break the barrier anyway.

SF: Yeah, you’re the Jackie Robinson of…

KAYE: [Laughs] No, no, no! That’s a really — that’s… sports did that.

Tragedies With Happy Endings

A Proud Benchwarmer was written and produced by Sam Fenn, Gordon Katic, Alexander Kim and Eli Yarhi. Fact checking by Lawrence Pinsky. Thanks to David Gutnick for his tape-sync. This documentary was produced by Cited and The Canadian Encyclopedia, which is a division of Historica Canada. It is broadcast with both groups’ permission. If you’d like to hear more of Sam's work, visit citedpodcast.com.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom