The following article is an editorial written by The Canadian Encyclopedia staff. Editorials are not usually updated.

Before Confederation, the right to vote in elections was restricted to a small, wealthy, property-owning elite. Because votes were declared publicly, elections were rowdy, highly competitive and even violent. Voting by secret ballot was first introduced in New Brunswick in 1855 and federally in 1874.

Democracy: An Unruly Affair

In the early days of democracy, voting was restricted to a privileged few (who owned enough property or money), and votes had to be declared publicly. The following description of an election in Montreal in 1820 was typical of the time:

“Passions ran so high that a terrible fight broke out. Punches and every other offensive and defensive tactic were employed. In the blink of an eye table legs were turned into swords and the rest into shields. The combatants unceremoniously went for each others' noses, hair and other handy parts, pulling them mercilessly... The faces of many and the bodies of all attested to the doggedness of the fighting.”

The idea that people should vote for their representatives is a powerful one. Like most historical movements, it was resolved in an untidy fashion over many years. In Canada, it took almost 150 years to sort out. There was always a great deal of uneasiness about the idea, and not only among the powerful elements of society. Many people felt that democracy would lead to social unrest and “mob rule.”

Then, as now, those already holding political power sought to influence the outcome. Before the secret ballot, there was ample opportunity to influence or intimidate voters as they went to publicly declare their choice to an official. Economic intimidation was another, equally blunt instrument. What man could risk voting openly against the wishes of an employer or landlord? The vague property qualifications that were required of anyone who wished to vote or run for office also left the system open to disputes and abuses.

Bribery and Bullying

A series of elections in Lower Canada (now Quebec) illustrates the messy nature of early elections. In the riding of Montarville on 11–12 October 1858, Alexandre-Édouard Kierzkowski, a civil engineer born in Poland, was returned as the successful candidate. He was credited with 2,056 votes, while John Fraser received 1,809 and Marc Amable Girard received 404. When the polls closed, Fraser filed a complaint charging that Kierzkowski failed to meet the property qualifications of an office holder. Kierzkowski made a countercharge that Fraser was guilty of bribery and corruption, having plied the voters with drink. After a year-long investigation, both men were disqualified — Kierzkowski for lacking the proper property qualification and Fraser for his misconduct.

In a subsequent by-election, Kierzkowski lost to Louis Lacoste by 29 votes, and he then registered a complaint. The persistent Kierzkowski then accepted the nomination for the riding of Verchères. Polling took place on 8–9 July 1861. The returning officer reported the results as Kierzkowski 858, Charles Painchaud 856, and the aforementioned John Fraser 1. Painchaud filed the inevitable protest and Kierzkowski was again declared unqualified to sit. Painchaud had little opportunity to enjoy his victory as the legislature was dissolved 12 days later.

These disputes over property qualifications and irregularities were common before voting rights were extended to all adults. In 1793, in Kings County, Nova Scotia, for example, the sitting member procured votes by selling land to voters for £5. In 1850. in Saint John County, New Brunswick, a candidate gained 250 votes by dividing a swamp into 250 fraudulent freeholds. Even the dead were solicited. In 1858, the Journal de Québec reported that votes had been cast “in the names of the living and the dead of all nations.”

Secret Ballot

Reformers concentrated their efforts on such issues as extending the right to vote and improving the voters’ lists and registers. But they also knew that true democratic elections demanded a secret ballot, not a public declaration to an official. The first use of a secret ballot in Canada was in New Brunswick in 1855. Britain resisted the change for more than 15 years, but corruption would not go away. The British Parliament finally passed the Ballot Act in 1872.

Canada’s newest province, British Columbia, enacted secret ballot legislation in February 1873. Ontario and the federal government followed in 1874, Quebec and Nova Scotia in 1875. Prince Edward Island introduced the secret ballot in 1877, rescinded it in 1879 and did not adopt it permanently until 1913.

“Democracy is the worst political system,” runs the old cliché, “except for all the others.” While the secret ballot has eliminated intimidation at the polling station, voters today wonder if they are any less manipulated by attack ads, image making and false promises.

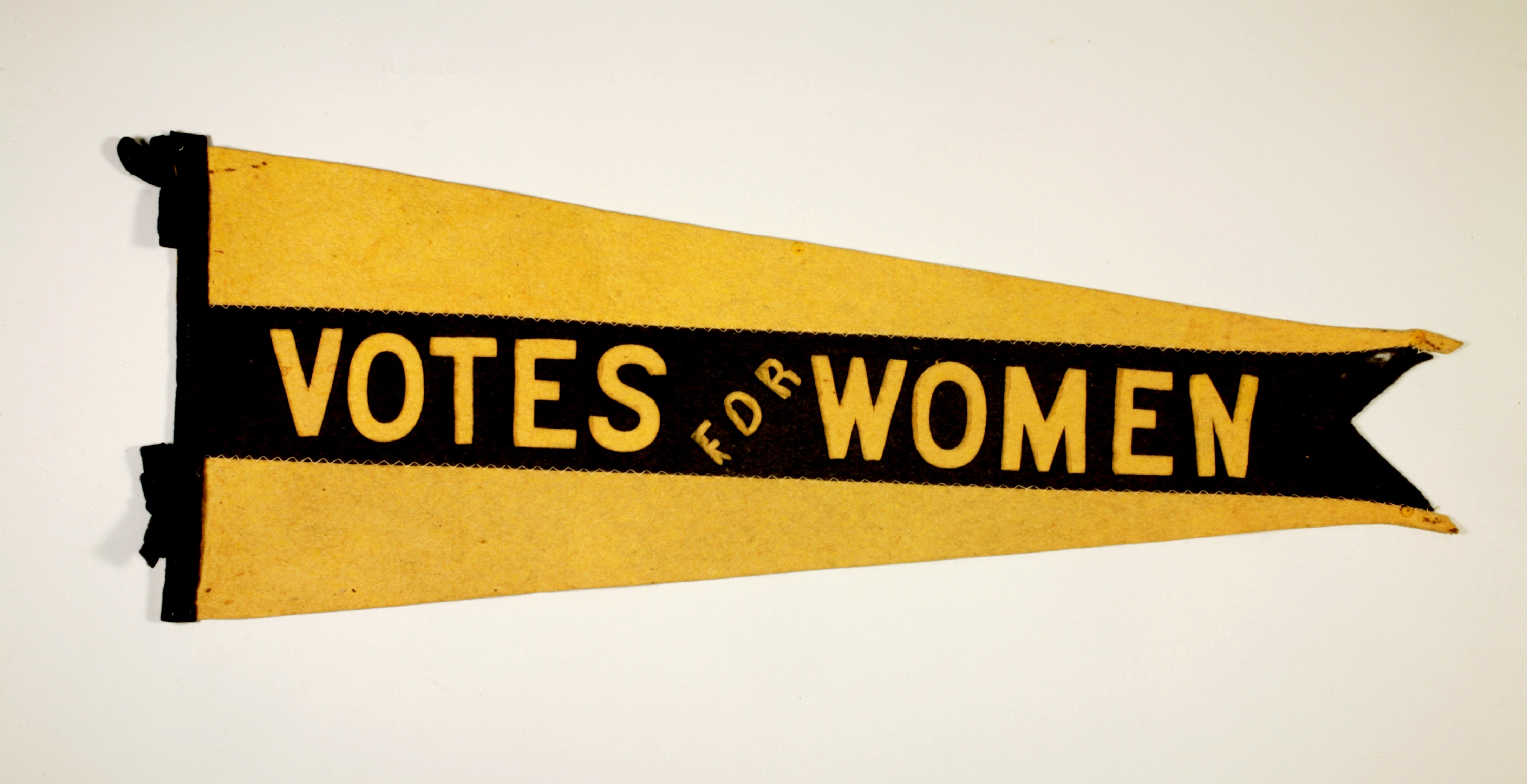

(See also Right to Vote in Canada; Voting Behaviour in Canada; Black Voting Rights in Canada; Political Participation in Canada; Women’s Suffrage in Canada; Canadian Electoral System; Electoral Reform in Canada.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom