On 28 January 1916, women in Manitoba became the first in Canada to win the right to vote .

That victory came after decades of struggle. After Manitoba's entry to Confederation in 1870, provincial law stated that, “No woman shall be qualified to vote at any Election for any Electoral Division whatever.” And though suffrage was extended to some property-owning women over time, including the right to vote in municipal (1887) and school board elections (1890), women had very limited voting rights (see Women’s Suffrage).

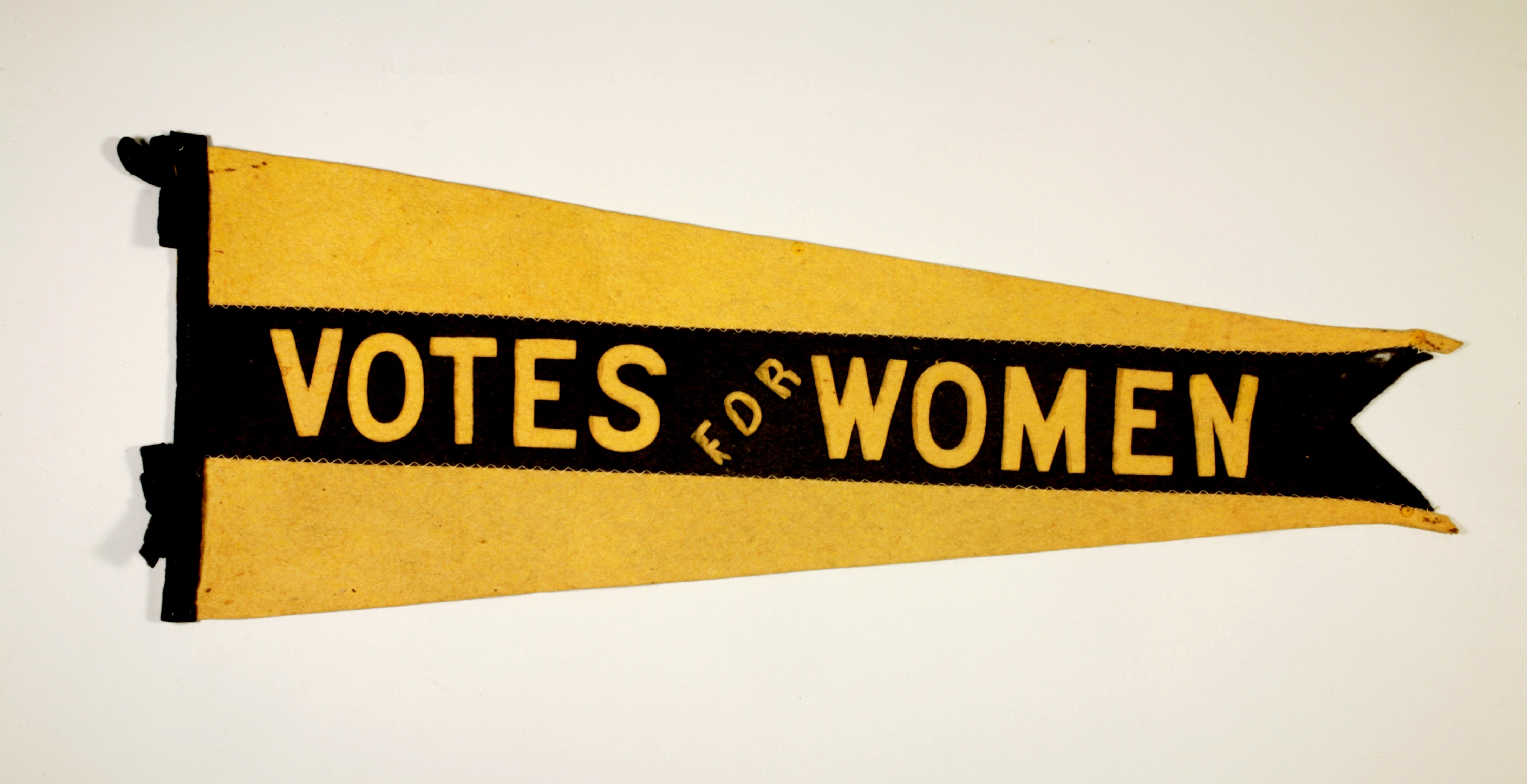

The women’s suffrage movement in Manitoba grew from grassroots campaigns that sprouted in the late 19th century. Like other contemporaneous provincial and national suffrage campaigns, it was led by women’s rights activists and temperance advocates, women who walked countless miles to put signatures on petitions, and who educated citizens on equal rights in the press and on speaking tours.

Though historical surveys are sparse — Catherine Cleverdon’s The Woman Suffrage Movement in Canada was published in 1950 — archival materials bring a textured understanding of the people, organizations and events that helped women win the vote.

But as we celebrate 100 years of suffrage, it’s important to note that not all women gained the right to vote in Manitoba in 1916 — or federally in 1918 for that matter. It would be a long road before First Nations and Inuit women (and men) won the franchise. The same was true for many Asian and South Asian communities. To learn more about the franchise in Canada, see Right to Vote.

Icelandic Women

The women’s suffrage movement in Manitoba gained steam when a group of Icelandic women organized a suffrage league there in the early 1890s. In Iceland, women could vote in church elections, and since 1882, widows and single women could vote at the municipal level. Many Icelandic women carried that growing support for equal rights to Manitoba, where they arrived in great numbers in the last three decades of the 19th century.

Icelandic women campaigned for suffrage for decades, petitioning the legislature and publishing a regular column in Heimskringla newspaper (founded 1886). While the Icelandic population remained somewhat isolated from the Anglo-Saxon majority, due to language and cultural differences, they did collaborate when sending delegations to lobby government.

The Icelandic Women’s Suffrage Society, called Tilraum (translates to Endeavour), was founded in Winnipeg in 1908, with Margret Benedictsson as its first president.

Margret Benedictsson

Margret Benedictsson (née Jonsdottir), journalist and social activist (born 16 March 1866 in Hrappsstadir, Iceland; died 13 December 1956 in Anacortes, Washington).

Margret and her husband, Sigfus Benedictsson, established the monthly magazine Freyja (woman) in 1898. The magazine featured serialized fiction, biographical sketches, poetry, literary reviews, letters, and a children’s corner. But it was also a place to discuss women’s suffrage. Freyja had 500 subscribers, including both men and women across Canada. It is often distinguished as being the only women’s suffrage publication in Canada at the time.

Benedictsson often wrote stories in the magazine under male names, such as Herold, in order for her work and ideas to receive serious consideration from both men and women. Such articles advocated political, social, legal and economic equality for women. She went so far as to encourage readers to withhold affection and sexual relations in order to influence men to vote for candidates supporting equal rights for women.

Amelia Yeomans

Amelia Yeomans (née LeSueur), physician, social and political reformer, temperance advocate, suffragist and public speaker (born 29 March 1842 in Québec City, Canada East; died 22 April 1913 in Calgary, AB).

Amelia Yeomans supported Icelandic suffragists and helped ally the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) with their cause. In 1893, Yeomans and the WCTU presented a petition to the provincial government calling for votes for women. Though it included some 5,000 signatures, it was dismissed.

In response, the WCTU sponsored what would be the first mock parliament in Canada, and Yeomans played the role of premier. Staged at the Bijou Theatre in Winnipeg on 9 February 1893, the mock parliament was a powerful medium in which suffragists made their arguments for the right to vote. It was also organized to raise funds and public support for suffrage organizations.

The Manitoba Free Press reported that at least 20 members of the Manitoba legislative assembly were in the audience — Yeomans had invited the entire legislature two days before — and that “wiser and better men left the hall than entered it during the early part of the evening.” It was followed by two suffrage petitions, each with thousands of signatures.

"[A woman is] a rational, independent organism endowed by the Creator with certain natural rights which no one may in-fringe without wrong-doing." — Amelia Yeomans, mock-parliamentary premier, 1893.

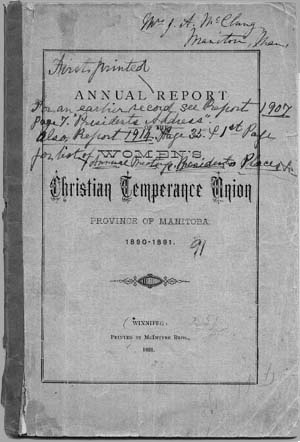

Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The temperance movement was a social and political campaign, advocating moderation or total abstinence from alcohol ( see Prohibition), prompted by the belief that drink was responsible for many of society’s ills. The most important temperance society for women in Canada was the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

In 1890, a chapter of the WCTU was established in Manitoba, and it quickly became the first English-speaking organization to officially support the women’s suffrage movement in the province. Many leading suffragists came to the cause by way of the WCTU, including journalist E. Cora Hind, Annie McClung, her daughter-in-law Nellie McClung, and Amelia Yeomans.

Since the prohibition of alcohol was considered a “local option,” local governments could hold referenda on the matter. Many women thought that the extension of voting rights to women would sustain prohibition, since it was believed that women were sympathetic to the cause. That conviction was assured in 1910, when prohibition was rejected in Manitoba by referendum — one in which women could not vote.

Equal Franchise Association

In November 1894, Yeomans and Hind announced the formation of the Equal Franchise Association (also known as the Equal Suffrage Club) at the end of a WCTU meeting in Winnipeg. Yeomans was the association’s first president. According to historian Catherine Cleverdon, “While men were welcomed [to the association] as members, Dr. Yeomans urged that women should be chosen as officers to give them much needed practice in planning and organizing.”

After the association worked for about 10 years with little publicity, it faded when Yeomans moved out of province. It would not be until 1912, with the establishment of the Political Equality League, that new life was breathed into the Manitoba suffrage movement.

Political Equality League

The Manitoba suffrage movement returned to the fore in the summer of 1912, when members of the Canadian Women’s Press Club in Winnipeg often met to discuss the matter, including Nellie McClung, E. Cora Hind, Francis Beynon and her sister Lillian Thomas. Early that year, they formed the Political Equality League (PEL) and launched a sharp, concerted campaign that pulled in support from the Manitoba Grain Growers’ Association, the WCTU and the Manitoba Direct Legislation League. Several men, including Grain Growers’ Guide editor George Chipman and journalist Fred Dixon, also joined the league. Before long, the PEL had 1,200 members.

In concert with other organizations, the Political Equality League printed pamphlets, lobbied government, lectured the public and circulated petitions. They also staged theatrical productions that shed light on women’s disenfranchisement, including the mock parliament of 1914.

Petitions, Petitions, Petitions

After receiving a petition with 20,000 signatures in 1913, the Manitoba Liberals agreed to endorse suffrage. Though members of the Political Equality League campaigned for their new allies during the 1914 election, the Conservative government of Sir Rodmond Roblin was returned to power.

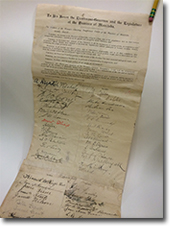

In 1915, the Roblin government was capsized by scandal and the Liberals swept to power. That August, Premier Tobias Norris pledged his government would grant women the vote if formally presented with a petition signed by 17,000 supporters. On 23 December, the PEL formally presented the Legislature with a scroll measuring 353 m and listing 39,584 signatures. A second petition accounted for 4,250 names collected by Amelia Burdett of Sturgeon Creek, Manitoba, age 94.

Winning the Vote

On 28 January 1916, Manitoba women became the first in Canada to win the right to vote and the right to hold provincial office. However, they could not vote in federal elections, a separate jurisdiction.

Meanwhile, pressure was mounting on federal politicians to enfranchise women. In the controversial Wartime Elections Act of 1917, the federal vote was extended to women in the armed forces, and to the female relatives of military men. On 24 May 1918, the majority of female citizens aged 21 and over became eligible to vote in federal elections, regardless of whether they had attained the provincial franchise. In July 1919, women gained the complementary right to stand for the House of Commons, although appointment to the Senate remained out of reach until after the Persons Case of 1929.

Sadly, the right to vote federally remained even further from reach for Asian Canadian women and Aboriginal women, who were finally enfranchised in 1948 and 1960, respectively.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

Women’s Franchise, Certification

of Signatures (courtesy Archives of Manitoba, Events 173/2, Presentation of petition by Political Equality League for enfranchisement of women, 23 December 1915, N9904).

Women’s Franchise, Certification

of Signatures (courtesy Archives of Manitoba, Events 173/2, Presentation of petition by Political Equality League for enfranchisement of women, 23 December 1915, N9904).