Who are Arctic Indigenous Peoples?

Indigenous peoples in Canada, both historical and contemporary, have inhabited six cultural areas that, unlike provinces and territories, do not have strict boundaries, and instead refer to areas in more general terms. The Arctic is one of these cultural areas. The others include the Plains, Plateau, Subarctic, Northwest Coast and Eastern Woodlands.

Referred to as Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland comprises those inland and coastal areas north of the treeline. It is for this reason that the terms Inuit — itself a generic term — and Arctic peoples are often used interchangeably.

There are nine main Inuit groups in Canada:- Labradormiut (Labrador Inuit)

- Nunavimmiut (Nunavik Inuit or Ungava Inuit)

- Nunatsiarmiut (Baffin Island Inuit)

- Iglulingmiut (Iglulik Inuit)

- Kivallirmiut (Caribou Inuit)

- Netsilingmiut (Netsilik Inuit)

- Inuinnait (Copper Inuit)

- Qikirtamiut (Sanikiluaq Inuit)

- Inuvialuit (Western Arctic Inuit or Mackenzie Delta Inuit)

A tenth group, the Sallirmiut (Sadlermiut), are no longer in existence.

In 2021, there were 70,545 Inuit in Canada, 69 per cent of whom lived in Inuit Nunangat.

The Inuit are not the only northern Indigenous peoples in Canada. In areas close to the treeline, Indigenous peoples, including some Innu, Dene and Cree nations, have traditionally occupied similar environments to the Inuit (though rarely at the same time), and have hunted and fished similar game species. These northern Indigenous peoples have lived in parts of the Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Québec and Labrador.

Geography and Traditional Territory

Inuit Nunangat is comprised of four regions: Inuvialuit (in the northern parts of the Northwest Territories and Yukon), Nunavut, Nunavik (in northern Québec) and Nunatsiavut (in northern Labrador.)

These arctic regions are characterized by long daylight hours in summer with moderate temperatures. Winters are long and cold, and at more northerly locations there is a mid-winter period when the sun is entirely absent. Plant cover may be continuous, especially in well-watered locations, although rocky outcrops and barren dry areas are common. Trees are entirely lacking in the Arctic, though low shrubby plants occur, including several varieties of edible berries. Landforms are variable, from lake-studded lowlands to glacier-strewn alpine areas.

Society

Historically, Inuit communities contained 100 –1,000 members. These regional bands were the most important social and political unit. Band members often congregated for short periods during the winter months, when people gathered in sealing or hunting camps.

Several regional bands made up the larger Inuit groups. Marriages occurred within these larger groups and all members spoke a similar dialect.

During the rest of the year, Inuit lived in smaller bands, often composed of two to five families. Each household generally consisted of a married couple and their children, though elderly or unmarried relatives might also be present. Many economic and social activities involved inter-household co-operation, and widespread sharing was, and still is, a fundamental characteristic of Inuit social life.

Most families who chose to live together were closely related, with leadership of the group generally assumed by the family heads. In some groups, the isumataaq, an informal leader who was often a young man with proven hunting and leadership skills, also held authority on social matters, such as adoption and marriage.

Family Structure

Marriage was nearly universal among Inuit and customarily took place in early adulthood; it was common for the young couple to reside close to the parents of one or the other spouse. Many households included adopted children, an indication of the high value accorded to children. Children were an important means of establishing valued inter-family relationships through adoption, engagements, adult-child relationships established at birthing ceremonies, and naming practices. The family was an important economic unit, relying on a decided division of responsibilities among all household members, including children and elderly relatives.

Inuit society associated birth with several socially significant rituals. Among some groups, in addition to an attending midwife, there was another adult who served as the child’s ritual sponsor, assuming responsibilities for the child’s moral upbringing. Throughout life, special terms of address were used. For example, according to a Netsilingmiut elder interviewed in 1991 for Betty Issenman’s Sinews of Survival (1997), a godfather calls his goddaughter arnaliaq, which means “making you a woman,” while she calls him sanajiarjuk, “dear little maker.” Naming occurred at birth and had special significance, as Inuit names included part of the identity and character of the name bearer.

The arrangement of children’s future marriages could occur at any time, even before birth. Young people promised to each other used a special form of address, and their families related in ways appropriate to the future relationship. Marriage, an exceptionally stable institution among Inuit, was customarily preceded by a period of trial marriage. Polygyny, having multiple wives, and more rarely polyandry, having multiple husbands, also occurred, but were not common practices.

Traditional Life

Food and Economy

Most Inuit groups based their economy on sea-mammal hunting, particularly seals. In summer and fall, many groups hunted caribou or moved to favoured coastal locations to hunt and fish a variety of game species. Fishing and food gathering (for bird eggs, shellfish and berries) were important seasonal activities, as were hunts for polar bear and whale. Though high value was placed on fresh food, people also preserved and stored goods for future use. Drying and caching in cool areas were common techniques, although several special techniques (such as storing in oil) were also used.

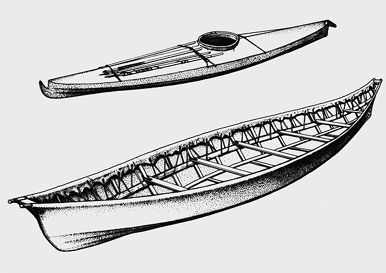

Traditional technology was based on locally available materials, principally bone, horn, antler, ivory, stone and animal skins. In some areas people used grass or baleen (the material used by whales to strain krill and plankton) for basketry and other containers. They also substituted wood or copper for antler or bone, and bird or possibly fish skins for animal skins. Many Inuit inventions are considered technological masterpieces for their resourcefulness and strength of design, like the igloo, the toggling harpoon head and the kayak.

There was an important relationship between location of settlements and seasonably available food resources. The composition of settlements might change periodically in response to social needs and desires to interact with kinsmen residing elsewhere. Many hunting methods became more effective when several hunters worked co-operatively, such as during winter seal hunting.

In many contemporary northern communities, foods such as fruit, vegetables and milk must be transported long distances. The resulting high costs, limited availability and lower quality of the food is somewhat eased by the availability of “country food” — wild foods such as seal, caribou, duck, whale and fish (see Inuit Country Food in Canada). A 2005 report found that 68 per cent of Inuk adults in Inuit Nunangat harvested country food. (See Social Conditions of Indigenous Peoples.)

Transportation and Dwellings

All Inuit used sleds and skin-covered boats, though regional variations in both design and use were common. Dogs historically served as hunting animals, locating seal breathing holes in the sea ice, hunting muskoxen, holding bears at bay and serving as pack animals in the summer. Men used single-seat kayaks for hunting sea mammals, and for hunting caribou in rivers and lakes. In the Beaufort Sea and along the Alaskan coast, large skin-covered umiaks were used for whale hunting, although in the Canadian Arctic (and Greenland) women more often used such boats to transport households from place to place.

The skin tent, often with a short ridgepole, was generally made from sealskins and weighted down along the ground with rocks. Among the Kivallirmiut, the tent was often conical shaped and constructed from caribou skins. When suitable snow was not available for igloos, or when away from the sites of sod and stonewalled houses, tents served as temporary shelters.

Igloo design varied. At winter settlements, the main living chamber could be quite large, perhaps four metres in diameter and almost three metres in height. In addition, igloos featured chambers for storage and an entrance passage, and often, extra living chambers attached to the side. In some regions it was customary to line the walls with caribou skins for insulation. Most igloos had a snow sleeping platform and a window (made from clear lake ice) set into the roof. Smaller, less elaborate igloos are still used during winter travel.

In the western Arctic, where driftwood logs were available, permanent dwellings were constructed for winter use. Windows in this case were made from translucent animal skin parchment.

Clothing

Inuit skillfully manufactured footwear and clothing from animal skins. Even though parkas, gloves and boots followed a similar basic design, regional variations in pattern and technique persisted. Most Inuit made sealskin footwear for both winter and spring or summer use; the latter were entirely waterproof. In some areas, caribou skin replaced sealskin, especially for winter boots.

The parka traditionally consisted of an inner and outer jacket, usually of caribou fur. Some groups wore sealskin parkas and pants in the spring and summer, and caribou fur in winter. Women’s clothing was often more elaborate than men’s, with a voluminous hood on the tailed and aproned parka. Women carried infants in a pouch against the woman’s back, not in the hood.

To adorn their bodies, women generally practiced facial and arm tattooing. Men sometimes had tattoos on their faces and bodies. Women also generally wore headbands made of copper or bone, while some men had facial piercings. Both men and women were known to have pierced ears and noses.

Culture

As in many Indigenous cultures, the drum is a sacred cultural item among the Inuit. Made by stretching an animal-skin membrane across a wooden hoop, drums served as traditional musical instruments. Among Western Arctic Inuit, several sitting drummers usually accompanied one or several dancers; whereas in the Central and Eastern Arctic, the drummer would not sing.

Following contact with outsiders, instruments such as concertinas, accordions, fiddles, harmonicas, jaw harps and, more recently, guitars became widespread. Square dancing (see Folk Dance), often in extended and intricate performances, sometimes without a caller, has remained very popular.

Inuit vocal games, also known as throat singing, occurred among some groups, usually performed by two women producing a wide range of sounds from deep in the throat and chest. This art is still practised in the Arctic.

Artisans made decorative art by sewing skins or inscribing on utensils. Recent innovations in Inuit art, such as soapstone carving, printmaking and wall hangings, stem from traditional skills, sometimes using new materials or techniques.

In terms of sport and recreation, many Inuit compete in physical challenges that test one’s ability to high-kick (one and two foot varieties), kneel-jump, and perform many other feats of strength and dexterity. Many of these games are featured in the Arctic Winter Games, held every two years in a new location across the Arctic, including Alaska and Greenland. The Games attract competitors from Inuit Nunangat, as well as from other arctic regions.

Cultural Change

Since contact with outsiders, Inuit society and culture has undergone change. The early adoption of iron tools, firearms, cloth, and wooden boats altered or replaced certain material items. The spread of Christianity resulted in the loss of many traditional religious ideas and practices, and Canadian law has been superimposed on customary law in areas concerned with marriage, dispute settlement and wildlife management. (See Indigenous Law.) Even the language has changed; written Inuktitut, for example, uses Latin script — the same letters as English and French — as well as syllabics.

Many items traditionally used by Inuit remain in use by all peoples in the Arctic; among these are harpoons used in marine mammal hunting, sealskin boots and caribou parkas required for winter hunting, and sleds used in winter travelling. Techniques of preparing animal skins and sewing skin clothing have also been preserved.

Important elements of the value system have also resisted change, including traditional childrearing practices, concerns about environmental matters, the continued survival of the Inuit language and culture, and respect for individual autonomy. (See Inuit Co-operatives.)

Religion and Spirituality

Prior to contact with Europeans, Inuit religious leaders were shamans, who underwent lengthy and arduous training. Shamans were intermediaries between the Inuit and the various spiritual forces that influenced activities. Inuit life required strict adherence to various prohibitions and rules of conduct, so the role of the shaman was usually to determine wrongdoers and to prescribe appropriate punishment or compensation. (See Religion and Spirituality of Indigenous Peoples)

Early missionary activity was similarly constituted, with many new rules and prohibitions introduced and penitence demanded after sinning. In the 20th century, the intensive efforts of missionaries led many Inuit to adopt Christianity; ordained Inuit clergy or catechists serve many communities.

Inuit mythology, a system based on oral traditions and used to explain and instruct daily life, has experienced resurgence as a vehicle for cultural vitality. Programs exist to support oral traditions and encourage interaction with traditional stories through youth and elders. Young Inuit are expected to learn by example, through close association with adults. Many of the values and beliefs of the society are demonstrated implicitly in behaviour. For instance, the constant sharing of food and other commodities exemplifies the value of generosity and co-operation, and discourages stinginess, greediness and selfishness. Stories that elders like to tell, especially to children, reinforce these important lessons.

The Inuit Language

Inuit in Canada traditionally speak Inuktitut, of which there are many different dialects. (See Indigenous Languages in Canada.) However, because of improved travel opportunities and the development of Inuit-language radio and TV programming, language differences are diminishing. (See Communications in the North and Indigenous People: Communications.) Traditionally, there was no written language, but after contact with missionaries, the Inuit widely adopted writing systems.

In the 2011 census, 34,110 people reported Inuktitut as their mother tongue, with 63.1 per cent of these residing in Nunavut and 32.3 per cent in Québec. In the majority of communities in both Québec and Eastern Nunavut, over 90 per cent of the population reported having Inuktitut as a first language. One exception is Iqaluit, which reported only 46.6 per cent. Percentages were significantly lower in Labrador; for example, Nain reported 36 per cent and Rigolet had only 5 per cent.

European Contact and Colonization

Evidence exists of Norse settlement in the Arctic in the 14th century. (See Norse Voyages.) However, the first sustained contact with outsiders occurred between Moravian missionaries and Labrador Inuit in the late 18th century. (See Moravian Missions in Labrador.)

At a few other locations in the Arctic, the Inuit and Europeans established fleeting trade contacts, but most contact occurred nearly a century later. During the latter half of the 19th century, explorers and commercial whalers introduced various trade items to the Inuit, though it was only following the end of commercial whaling, effectively after 1910, that trading posts became more or less permanently established in the arctic regions.

Inuit were largely ignored by the federal government until 1939, when they were deemed the government’s responsibility. During the Second World War, Inuit were given disk numbers in lieu of names, for ease of government administration. (See Project Surname.) After the war, there was an intensification of government activity, including the establishment of schools, nursing stations, airports and communication installations, and housing programs in the newly established settlements and hamlets. These impositions caused much cultural tension, as many Inuit were forcibly relocated to areas with which they were unfamiliar (see Inuit High Arctic Relocations in Canada).

Political Organizations

In the early 1970s, a national organization, the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (now known as Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami), was established to protect Inuit cultural and individual rights. The organization created several agencies in response to expressed needs. An Inuit Language Commission, for example, was formed to seek the best means of ensuring the increased use of Inuktitut for governmental, educational and communications purposes, and a Land Claims Office was established to research and negotiate Inuit land claims.

Many of these issues, such as protection of the arctic environment, are international in scope. Therefore, an international Inuit organization, the Inuit Circumpolar Council, was formed with committees seeking to strengthen pan-Inuit communication, cultural and artistic activities, and international co-operation in environmental protection. This organization has affiliation with numerous international bodies, including the United Nations, thereby ensuring that Inuit concerns become widely understood throughout the world.

Contemporary Life

Significantly altered by the long-lasting effects of colonization, many northern communities face significant socio-economic challenges, such as overcrowding, food scarcity, chronic health issues and high rates of youth suicide. (See Social Conditions of Indigenous Peoples and Economic Conditions of Indigenous Peoples.)

A 2006 survey found that in Inuit Nunangat more than 15,000 Inuit were living in overcrowded conditions and were the most likely to live in households with more than one family. Living conditions and lack of access to health care partially contribute to an increase in chronic health conditions, including obesity, diabetes and respiratory infections. The suicide rate among Inuit youth is markedly higher than for the rest of Canada, making suicide prevention a key priority for continued cultural growth. ( See Suicide among Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Despite these challenges, Inuit peoples in Canada have celebrated many achievements in numerous fields, most notably self-government and the creation of Nunavut. The Inuit have also been active in discussions surrounding environmental policy, business and education in the north and the revitalization of Inuit culture and language.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom