Brewing in Canada evolved from a household necessity into a commercial industry that, while short lived in New France, grew rapidly under British rule. From its regional roots to national consolidation and the rise of the craft beer movement, the brewing industry has both shaped and adapted to Canadians’ tastes. Aside from a brief period of Prohibition, it has also been a large, stable source of tax income for governments. In 2016, beer accounted for roughly $13.6 billion of Canada’s gross domestic product, or 0.7 per cent of the economy. The industry employs nearly 149,000 people, or 0.8 per cent of Canadian workers.

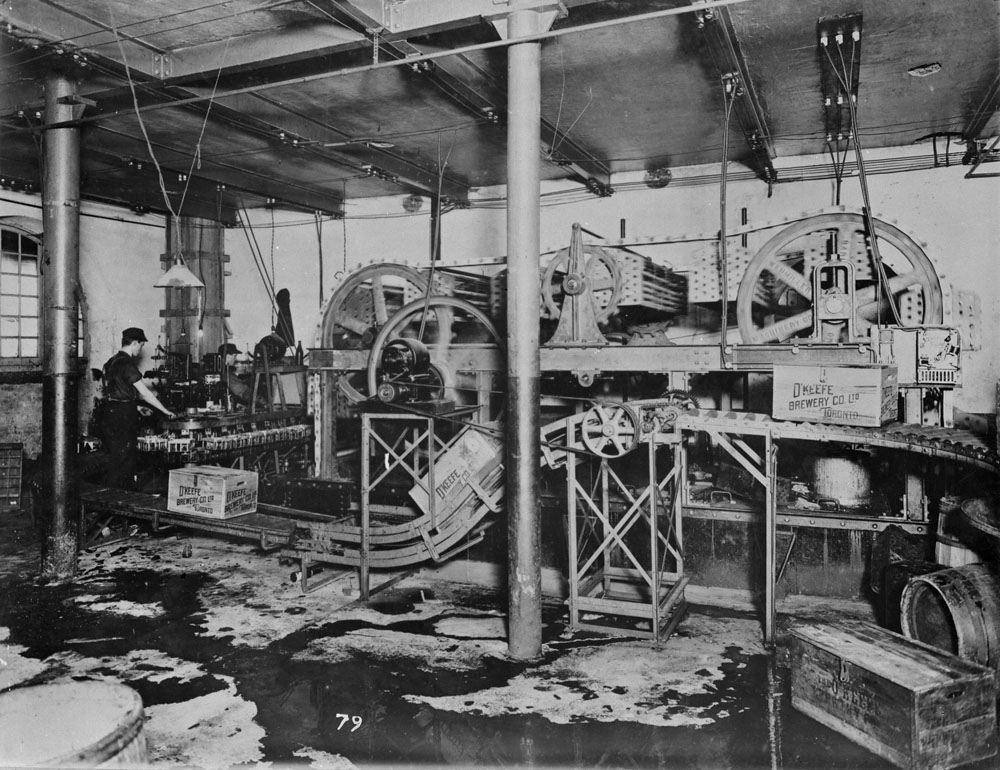

Interior of O’Keefe Brewery, date unknown.

Key terms

Canadien: A French Canadian. In the late 17th century, Canadien meant a settled resident of the colony or one born there, as opposed to a recent arrival from France.

Capitalism: An economic system in which private owners (rather than the state) control industries and collect profits.

Colonialism: Control of a people or place by another power for economic gain.

Conglomerate: A corporation composed of several different companies that have merged.

Consolidation: The fusion of small companies into larger ones.

Gross domestic product (GDP): The value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a year.

Hops: The ripe cones of the hop plant, used as a bittering agent in beer.

Malt: A grain, typically barley, that has been prepared for brewing through steeping, germination and drying.

Oligopoly: A state of limited competition between a few producers sharing a market.

Prohibition: A ban by law on the manufacture and sale of alcohol.

The Big Three: Labatt, Molson and Canadian Breweries Limited, Canada’s three largest brewing companies after the Second World War.

History of Brewing in Canada

Domestic Brewing in New France

Brewing began in Canada with the first settlers and traders. In New France, where European grape varieties used for wine and brandy did not thrive, beer was made not for want, but out of necessity. In colonial times, milk and even water were full of dangerous microorganisms that often caused people to get seriously ill (see Microbiology). But beer was relatively free of such dangers. The long boils involved in brewing killed almost every disease-causing agent. In addition, beer’s unique combination of high acidity, hops and alcohol was a brew in which harmful bacteria rarely survived.

The first brewers in New France were domestic. They were people like Louis Hébert, who was among the first settlers in New France to plant crops and harvest the land. Hébert arrived in the colony in 1617 and immediately planted wheat for bread and barley for beer. A born-and-bred Parisian, Hébert would have preferred to make wine, but the climate and short growing season in New France made this practically impossible (see also Wine Industry).

Like many of his fellow settlers, Hébert and his wife often brewed their beer in the same pot or kettle that they used for preparing the family’s meals. Beer required few ingredients and only basic equipment: a few handfuls of grain, some water, yeast and a pot or a kettle were enough to get the process started. Often colonists like Hébert added a combination of their favourite ingredients to their beer: things like molasses, dandelions, ginger, maple syrup, spruce boughs, checkerberries, sassafras roots and hops. There are very few written records of these domestic brewers, but we know that the colonial authorities tried, especially in the 17th century, to encourage production of beer in New France homes.

First Brewery (1647)

Since their arrival in New France in 1611, the Jesuit Fathers had been deprived of the daily ration of wine they had received in France. Without wine, they, too, turned to beer. In March 1647, they built a brewery. Like all breweries of the early 17th century, it was a small operation, in this case involving a single brewer. Le journal des Jésuites recorded that “our Brother Ambroise had made [brewing] his occupation from the first to the twentieth day of that month.” Father Ambroise’s brew was exclusively for the wine-deprived Fathers. Thus, in New France, the art of brewing was practised in the homes and religious houses of the colony. Small-scale and localized, brewing emerged for practical rather than commercial purposes.

First Commercial Brewery (1671)

The driving force behind the birth of commercial brewing in Canada was Jean Talon, the energetic and powerful intendant (i.e., administrator) of New France. Talon had grown up near the beer-producing Artois region of northern France. He had also served as an administrator in French Flanders and Hainaut, where people drank more beer than elsewhere in the country. In addition to his cultural connections to beer, he had moral and economic reasons for building Canada’s first commercial brewery.

A brewery would diversify the economy, which was in disarray following the outbreak of the Beaver Wars in 1642. Talon believed that a commercial brewery would encourage people to farm because “they will be assured that the excess grain will be used for making this weaker drink.” A brewery would also improve the colony’s balance of trade, according to Talon. Through brewing, domestically grown ingredients could be exported as a more valuable product (beer). Talon thought this would limit imports of more expensive drinks like wine and brandy (see also International Trade). Morally, a brewery would draw people away from the stronger “demon drink,” brandy. According to Talon, brandy was turning the “savages” and Canadiens into “destitute drunks.”

On 5 April 1671, Jean Talon wrote to the King of France, Louis XIV, proudly declaring: “the brewery is complete.” There was nothing like it in the colonies of the Americas. Fully state owned and controlled, the massive, state-of-the-art Brasserie du Roy could make 4,000 barrels of beer per year. To put that number in perspective, some 50 years later, the typical American brewery was about half that size. And when John Molson began brewing in Montreal a century later, he produced only 120 barrels of beer per year. Talon’s brewery could make 33 times that amount at a time when the population of New France was approximately one-twentieth of what it was in 1786, when Molson started brewing.

Unfortunately, there was little appetite among the local population for beer before the British Conquest (1759–63). Unlike Talon, most of the pre-Conquest immigrants came from France’s west coast, the Southwest and the Paris region, where wine was the preferred alcoholic beverage. With very little local demand the brewery was closed in 1675 and sold a decade later. It was eventually converted into the intendant’s palace (see Intendant’s Palace Archaeological Site). Talon believed in mercantilism, the dominant economic system of European nations at the time. Mercantilist governments sought wealth by monopolizing industry and trade. But in his rigid application of this system, Talon made his brewing industry insensitive to local tastes. It lacked any understanding of the workings of a diversified economy unique to New France.

Brewing Industry in British North America

Molson Brewery (1786)

Commercial brewing re-emerged after the Conquest of Quebec in 1759. When the British settled in Quebec after 1763, they brought a strong capitalist spirit and a thirst for the culture of home, including beer. They began to breathe new life into the dying colonial brewing industry.

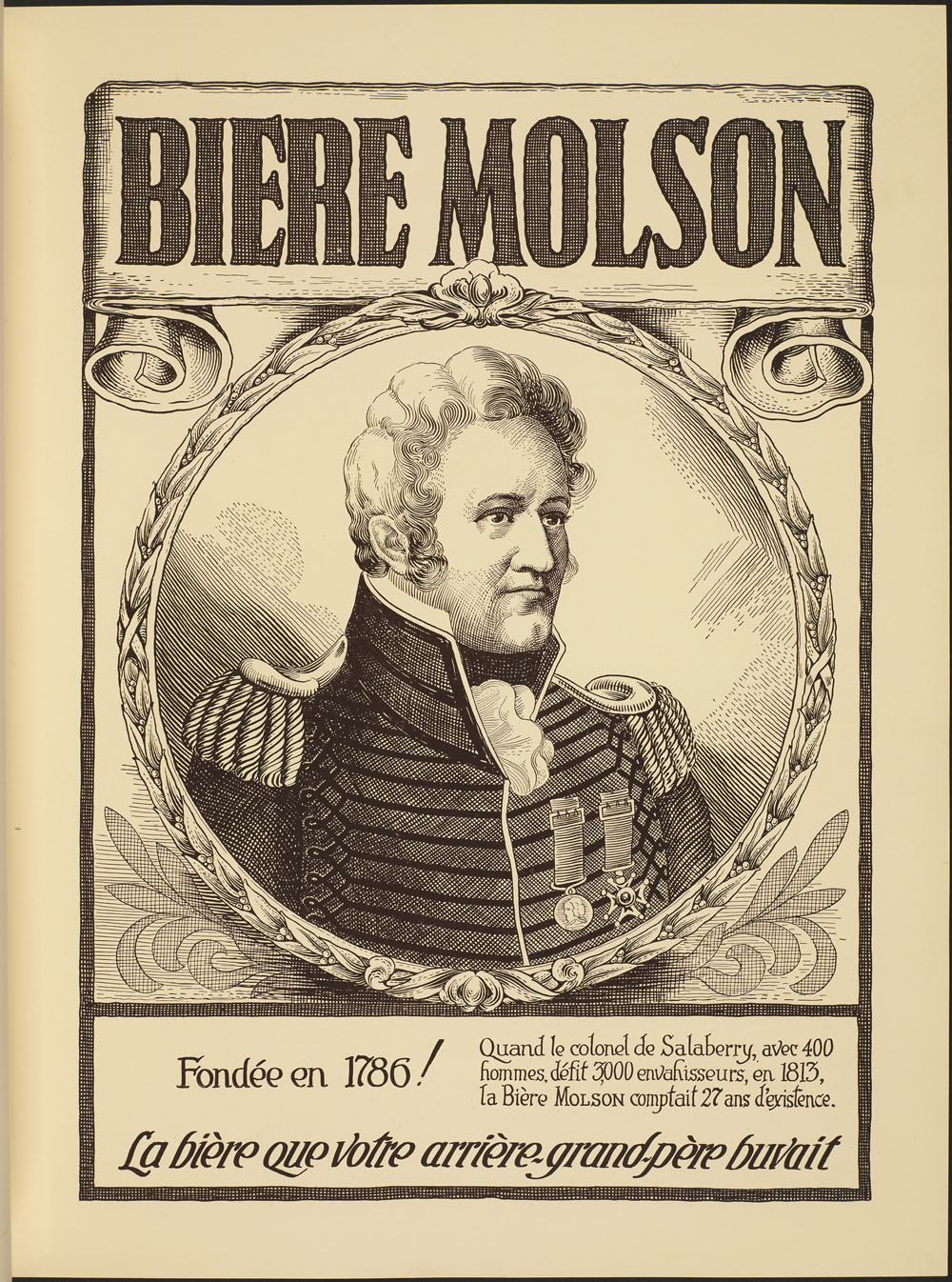

These newcomers did not repeat the errors of Jean Talon. The best of them grew their breweries slowly, reinvesting their profits and increasing their output to supply the ever-expanding colonial beer market. The most successful of these English-speaking brewers was John Molson (see also English-Speaking Quebecers). His brewery, founded in 1786, became the longest-surviving family firm in Canadian history. Indeed, of all the firms of 18th-century Montreal, only Molson’s (now in the form of Molson Coors Brewing Company) and the Montreal Gazette newspaper (est. 1778) still exist today.

Molson embodied the spirit of colonial capitalism. He had not immigrated to Quebec to brew beer. Rather, he had come seeking his fortune. Brewing was a means to an end. Indeed, he knew almost nothing about the art and science of brewing when he arrived in British North America (now Canada) in 1782. But the young settler had an eye for economic opportunity. He was ambitious, eager to learn and determined “to do something for myself.”

Located at the junction of St. Mary’s Current and the St. Lawrence River, the Molson brewery was just a short distance beyond Montreal’s eastern wall. With about 8,000 residents in 1782, Montreal was a strategic place to establish a brewery. Most of the city’s merchants were English or Scottish immigrants. They favoured the ales and porters of the old country. In addition, there was a high demand for beer among the British garrison troops stationed in the city and at nearby posts, such as Fort Chambly and Fort Saint-Jean on the upper Richelieu River. Soldiers received enough beer money to buy five or six pints of beer a day. This gave an immediate incentive to anyone in British North America to profit from their knowledge of the art of brewing. Thomas Carling, John Kinder Labatt and Susannah Oland (see Moosehead Breweries Ltd.) were among those who did.

Molson tapped into the rising demand for beer and soon found that he could not brew enough to satisfy his clientele. Part of the reason for the popularity of Molson’s beer was that it was cheap, selling for just five cents a bottle. But it was also of a better quality than most other brews available in the colonial outpost. The beers imported from the British Isles would have tasted flat and stale after being sloshed around in barrels in the bottom of a ship for a couple of months. Molson’s beer, by comparison, was delightfully fresh. Far less carbonated than today’s beers, the dark amber brew would have tasted primarily of malt (see Barley). When fresh, it would have been reminiscent of recently baked bread.

19th-Century Growth of Competition

Funnelling all his profits back into the business, Molson grew his brewery to the point that by 1796 he was making 54,000 barrels of beer a year. This was more than 13 times his output just a decade earlier. Nevertheless, it wasn’t enough to prevent the growth of competition. Molson’s main competitors were Thomas Dunn and Thomas Dawes.

Dunn was a miller-turned-brewer who in 1790 had started a business producing fine ales at La Prairie, just across the St. Lawrence River from Montreal. The company prospered. By 1808, with the promise of a large market for his brew in Montreal, Dunn moved his establishment from the south shore to a site on Notre-Dame Street.

Thomas Dawes, on the other hand, had set up his brewing operation just west of Montreal, at Lachine. The brewery that he founded remained in the family for several generations before becoming a cornerstone of the National Breweries conglomerate in the early 20th century.

Colour lithograph made ca. 1865–70.

The advent of the railway transformed the colonial brewing industry in the 1850s (see also Railway History). Trains finally made it possible to continue trade and commerce all year long, even in the harsh winter. Brewers quickly recognized the blessings of railroad transportation, especially after the introduction in the 1870s of the refrigerated boxcars that kept beer cold and fresh. In railway cars, beer was less likely to spill, spoil or go stale. A greater volume could be transported safely and conveniently, costing less for producers and consumers. The railway eliminated the “tariff of bad roads,” the high transportation cost that protected artisanal brewers in small, local markets. It laid the groundwork for the concentration of industrial production in a handful of metropolitan centres.

By extending the range of cheap overland transportation, the railway created the conditions necessary for the rise of mass-produced beer. As the most enterprising brewers found new consumers for their products, they expanded their plants to meet the new demand. As a result, the Canadian brewing industry shifted into a vigorous new era of industrialization and regionalization. A relatively small group of brewers came to dominate the central Canadian market. By the onset of the First World War, brewing had emerged as a vibrant and significant industry.

Prohibition in Canada (1916–30)

A man carrying a keg of beer during prohibition. Photo taken in Toronto, Ontario, on 16 September 1916.

Prohibition emerged in the years leading up to the First World War. It was part of a broader impulse in North America to regulate the production and consumption of alcohol. In Canada, due to the division of powers between the federal and provincial governments, Prohibition lasted longer in some regions than in others. Under the terms of the nation-forming British North America Act of 1867, the provinces have the power to regulate the retail sale of intoxicating drink. The federal government, meanwhile, has the power to regulate production.

The first province to “dry” was Prince Edward Island. Its Prohibition period lasted the longest, from 1901 to 1948. Nova Scotia followed (1916–30), then came Ontario (1916–27), Alberta (1916–24), Manitoba (1916–23), Saskatchewan (1917–25), New Brunswick (1917–27), British Columbia (1917–21) and the Yukon Territory (1918–21). Newfoundland, which was not part of Canada at that time, imposed Prohibition in 1917 and repealed it in 1924. Quebec’s 1919 experiment with banning the sale of some alcoholic drinks lasted only a few months and did not include beer. The Protestant moral urge toward Prohibition that existed in English Canada was simply not evident in the mostly French-speaking and Roman Catholic province of Quebec.

The temperance acts in each of the Canadian provinces varied. Generally, they closed legal drinking establishments and outlawed the sale of alcoholic beverages above 1.25 per cent alcohol by volume (ABV). They also forbade the possession and consumption of alcoholic drinks outside private dwellings.

Prohibition had a devastating effect on the Canadian brewing industry, cutting the number of breweries roughly in half. The personal fortunes of many brewers were lost, legacies vanished and hundreds of well-paying jobs disappeared. Those breweries that survived sometimes did so by bootlegging (illegally selling) beer and hard liquor to the United States, which experienced its own Prohibition between 1920 and 1933. The movement did not, however, live up to activists’ promise that it would cure all of society’s ills. As a result, Prohibition had ended in most provinces by 1930.

Postwar Consolidation: The Big Three

After the Second World War, a national brewing oligopoly emerged that was made up of the “big three” brewers: Labatt, Molson and Canadian Breweries Limited. The first truly national brewery was Edward Plunket Taylor’s Canadian Breweries Ltd. Having built up a regional giant in Ontario after Prohibition, the ever-ambitious Taylor set his sights on conquering the national market.

In theory, Taylor could have gained a national presence by shipping beer east and west from his plants in Ontario. Such was the approach taken by the “shipping brewers” (e.g., Anheuser-Busch, Schlitz, Miller and Coors) in the United States. But as Taylor noted in a confidential memo, the strategy would not work north of the border. “The immense distance in Canada,” he stated, “means it is not practical for breweries in the east to ship to the west and compete with western breweries.” In addition, provincial governments taxed out-of-province beer. The taxes often increased the price of import beer by 30 per cent. Therefore, Taylor concluded that the proper course was “to purchase two or three prosperous western concerns.”

Interprovincial trade barriers, along with the provincial jurisdiction over the retail sale and distribution of alcoholic drinks, local sensitivities, and the federal government’s permissive policy towards takeovers, all combined to make the acquisition of small- and medium-sized firms the main route toward market consolidation in Canada. To become truly national, the Big Three had to have a physical presence in each region. The result was that the Canadian brewing industry took on a multi-plant form after the Second World War.

In 1945, the Canadian brewing industry consisted of 61 breweries (28 in the West, 29 in Ontario and Quebec and 4 in the Maritimes) producing 159 brands. Not a single brewery was truly national, however. The biggest were regional concerns, catering almost exclusively to beer drinkers in their home provinces. But by 1962, the Big Three produced almost 95 per cent of the beer sold in Canada. Most of the 61 breweries that operated in 1945 were still producing beer, but nearly half of them were owned by the Big Three. Labatt, Molson and Canadian Breweries Ltd. had a physical presence in every region of Canada except the Maritimes and Northern Ontario, and their national brands dominated the market place.

These postwar acquisitions completely changed the market structure of the Canadian brewing industry. With the Big Three vying for the same national market, competition took the form of advertising and sales promotion. At a time when the price of beer was fixed by the various liquor control boards, advertising became essential for a brewer’s survival. The Big Three succeeded because they were able to produce a small number of standard national brands with mass appeal, like Labatt Blue, Molson Canadian and Carling Black Label. They marketed these brands with sophisticated, expensive advertising campaigns. The result was the extinction of local styles and the homogenization of the survivors into similar-tasting pale ales, lagers and ales. The advantage of the Big Three was thus directly related to the size of their promotional spending and the use of the national media, as well as their ability to control the channels of distribution.

Late 20th Century

By the late 1970s, some Canadians were getting tired of the brands of the Big Three, which they criticized as bland and similar tasting. “Like tasteless white bread and the universal cardboard hamburger,” wrote one of the pioneers of the craft beer movement, Frank Appleton, in Harrowsmith magazine, “the new beer [of the Big Three] is produced for the tasteless common denominator. It must not offend anyone, anywhere.” Appleton’s 1978 article urged people to brew their own beer and ultimately inspired a microbrewing movement. During the 1980s, new craft breweries started to appear in Canada.

The merger of Carling O’Keefe (previously Canadian Breweries Ltd.) with Molson in 1989 reduced the number of big brewers in Canada to two. In 1995, Labatt was bought by the Belgium-based brewer Interbrew (see Belgian Brewery Buys Labatt). And in 2005, Molson merged with Colorado’s Adolph Coors Company ( see Molson to Merge with Coors).

21st Century

Today the Canadian brewing industry is made up of two national brewers (Labatt and Molson), which dominate the domestic beer market and are controlled by foreign firms, and a large and growing number of craft breweries. In 2017, there were 817 operational brewing facilities across the country. Over half of these were located in Ontario and Quebec. In Canada, the number of brewing facilities per every 100,000 drinking-age adults increased from 2.4 in 2016 to 2.8 in 2017, a growth of 16.8 per cent. Using the same per capita measure, New Brunswick has the most operational brewing facilities with 6.5 and Manitoba the least with 1.0.

Types of Beer

Beer is a generic term that includes lager, light beer, ale and other styles. Of the range of beer types available to consumers, lager accounts for 59 per cent of sales in Canada, followed by light beer (22 per cent) and ale (10 per cent).

The difference between lager (from which light beer is derived) and ale is that lager is lighter in taste and is made with a type of yeast that drops to the bottom of the fermenting tank. More hops are used to brew ale and the yeast rises to the top of the tank. Less than 1 per cent of the market is taken by stout (heavy-bodied darker beer brewed with roasted malt and more hops) and porter (a fruitier, sweeter version of stout).

Light beers, containing up to 4 per cent alcohol by volume, were introduced in Canada in the 1970s. Regular-strength Canadian beers generally contain 5 per cent alcohol by volume. Since the 1980s, large and small brewers have expanded their range of products to offer consumers more selection to meet different tastes. New brewing technologies and processes have produced different styles of beer, including the following that are generally available in Canada: amber, blonde, brown, cream, dark, fruit, golden, honey, India pale ale, light, lime, Pilsner, red, strong and wheat.

Brands and Advertising

Developing popular brands is essential for success in the brewing industry. For a brewer, brands add value by sustaining a constant income stream sourced in the consumer’s tendency for long-term brand loyalty. While a beer brand’s “identity” is developed over time, it is usually embedded in a particular culture and a specific set of values. Brand identity is particularly important in the brewing industry, where products tend to have long life cycles and very strong associations with tradition, heritage, craftsmanship, naturalness and the place of origin. These elements give a brand its air of authenticity, which, according to a number of recent studies, is a cornerstone of modern marketing.

By the end of the 19th century, various Canadian brewers were engaged in brand-driven marketing. The most innovative brewers designed their advertisements to highlight the qualities of a particular brand. The ads clearly identified the product, the manufacturer, and why the product was worth purchasing. (These are the essential themes of brand-driven marketing.) The tactic encouraged product recognition and kept the brewer’s ads from disappearing in the cluttered newspaper pages of the Victorian age. Advertising proved valuable in the struggle to distinguish a brewer’s brand from its competitors.

After Prohibition ended, governments placed tight restrictions on beer advertising. Ads had to meet provincial liquor control board standards. These could range from regulations on their content to total advertising bans. Brewers could not advertise their products on outdoor signs or billboards. Nor could they promote them on the radio or television until the mid-1950s. And even after these regulations were relaxed in 1955, commercials could not feature a person drinking, or a beer bottle, or a glass of beer.

Canada’s biggest brewers found ways around advertising restrictions during the 1950s and 1960s. Labatt, Molson and Canadian Breweries Limited advertised their beers in magazines like Maclean’s and Saturday Night. These magazines were published in Quebec (which had softer rules on promoting beer) but sold across the country. Canadians were thus aware of the Big Three’s brands before there was a truly national market for them. These same brewers also ran ads in the United States, targeting Canadian audiences of US magazines and television shows.

Nevertheless, it has been difficult for brewers to create national brands because of the regional, linguistic and religious diversity of the nation. The first truly national brand was Labatt Blue, rolled out in the late 1960s. By the early 1970s, it was the first brand to have a significant presence in each region of Canada. Thereafter other national brands emerged, like Molson Canadian.

The difficultly of developing successful national brands led the Big Three Canadian brewers to license the right to brew popular American brands and market them in Canada. In 1980, Labatt licensed the right to brew “the King of Beers,” Budweiser. Labatt first rolled out the product in Alberta and Saskatchewan, provinces where there had been a long tradition of brewing and drinking American-style lagers. It wasn’t until 1981 that the Canadian brewer made Budweiser available to beer drinkers in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia. By 1982, Budweiser accounted for about 7 per cent of total Canadian beer sales. Shortly thereafter, Carling O’Keefe licensed the right to brew the popular American brand Miller High Life. Molson followed suit three years later when it signed an agreement to brew Coors and Coors Light under licence in Canada.

Today the Canadian mass beer market is dominated by foreign brands like Budweiser, Coors and Stella Artois.

Economic Contributions

The brewing industry’s contribution to the federal and provincial treasuries has always been important and at times fundamental. Breweries must obtain licences to operate for a fee from both the federal and provincial governments. In addition to federal excise and sales tax, breweries have to pay provincial sales commodity taxes or charges. The brewing industry has been better able to tolerate tax increases than most other commodity industries. This fact may partially explain why beer and alcohol have long been so heavily taxed.

Beer still contributes very substantially to Canada’s tax income. In 2017, the Canadian beer economy generated a combined $5.7 billion in tax and other income for federal, provincial/territorial and municipal governments. Canada’s levies are among the highest beer taxes in the world. For every dollar the consumer spends on beer, about 47 cents is tax. At this level, Canadian taxes are about five times higher than taxes on beer bought in the United States.

Beer’s share of Canada’s gross domestic product was roughly $13.6 billion in 2016, representing 0.7 per cent of the Canadian economy. In 2015–16, beer sales totalled $9.2 billion in Canada, making up 41.5 per cent of total alcoholic beverage sales. Over the preceding decade, beer sales grew at an average annual rate of 1.7 per cent. In 2016, the industry employed nearly 149,000 people, or 0.8 per cent of Canadian workers.

Canadian exports of beer (primarily to the United States) totalled $196 million in 2018. From 2014 to 2018, domestic exports in this industry declined by 9.1 per cent. In 2017–18, 84 per cent of the beer consumed in Canada was produced by Canadian breweries. This includes foreign brands brewed under licence.

Brewing and the Environment

On the retail end, vendors not only sell beer but handle bottle returns. Approximately 30 per cent of all beer sold in Canada comes in returnable and reusable bottles. Ninety-nine per cent of those bottles come back for cleaning and refilling. A bottle can be reused 15 to 20 times, preventing enormous wastage. Once a bottle is spent, it is crushed and sent to glass-makers for the manufacture of new bottles.

Aluminum beer cans, comprising about 62 per cent of all sales, are also crushed and recycled, as are the beer cartons. Roughly 87 per cent of aluminum cans are returned to vendors for recycling.

Draught beer is sold in reusable kegs that can last more than 30 years before they, too, are crushed and recycled. Even the husks of the spent grain used in the brewing process are collected and sold as animal feed.

The brewing process uses massive amounts of energy and water. To help brewers limit their environmental impact and reduce production costs, Natural Resources Canada published Energy Efficiency Opportunities in the Canadian Brewing Industry (1998) in collaboration with the Brewers Association of Canada. The first edition was reprinted in 2003 due to popular demand. A revised and updated second edition appeared in 2012.

Following several pilot projects that tested innovative wastewater management technologies at Ontario craft breweries, Gravenhurst’s Sawdust City Brewing installed the BRÜ CLEAN system in 2017. It was the first on-site commercial system for wastewater management adopted at a Canadian brewery. A Bloom Centre for Sustainability report on the Ontario pilot projects argued that such systems can help breweries reduce water consumption and cleanly manage wastewater while cutting overhead costs.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom