Political Change and Population Growth

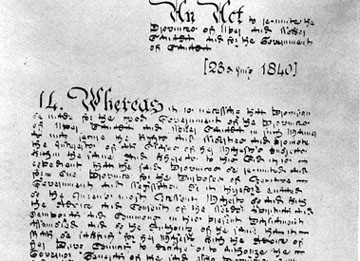

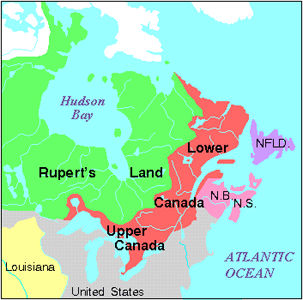

In the early 1860s, Canadian politics were in a state of crisis. Upper and Lower Canada had been united into the Province of Canada in 1841. (See also: Act of Union.) The province consisted of the mostly English-speaking Canada West (formerly Upper Canada, now Ontario) and the mostly French-speaking Canada East (formerly Lower Canada, now Quebec). But the union had failed to contain the growing ethnic and religious tensions in the two colonies. The political system was coming close to paralysis.

Canada West and Canada East were given the same number of seats in the colonial legislature. But Canada West had fewer people than Canada East. This meant English-speaking Canadians were over-represented in the legislature. The system was designed to protect the English-speaking minority in the united colony from French Canadian dominance. The goal was to assimilate French Canadians to English Canadian culture and norms.

Immigration from Britain and Ireland in the 1840s and 1850s created huge population growth, mostly in Canada West. By 1861, Canada West's population exceeded that of Canada East by more than 250,000 people. It was now the French Canadians who were over-represented in the legislature. A growing number of English Canadians regarded this as unfair.

Alliances and Tensions

French Canadian politicians were determined to protect their language, culture and religion from English-Protestant influences. They made alliances with those in Canada West who supported the idea of responsible government. This was a more democratic system of government. It was responsible to the elected members of the legislature rather than to British-appointed governors.

In Canada East, French Canadian Conservatives were a powerful political force. They were closely connected to the Catholic Church. In the 1850s, French Canadian leaders made an alliance with Conservatives in Canada West. This gave them considerable control over the levers of power. They had succeeded in turning a political system that was designed to assimilate them to their advantage.

However, for a growing number of people in Canada West, this amounted to “French domination.” As this view spread, Liberals, Reformers, and Radicals (also called Clear Grits) became more popular in Canada West. Many were hostile towards and suspicious of Roman Catholicism.

In the early 1860s, there was a Liberal-Reform majority in Canada West, and a Conservative majority in Canada East. As a result, the province became increasingly unstable. It lurched from one cobbled-together government to another, in an atmosphere of seething resentments and fears.

Representation by Population

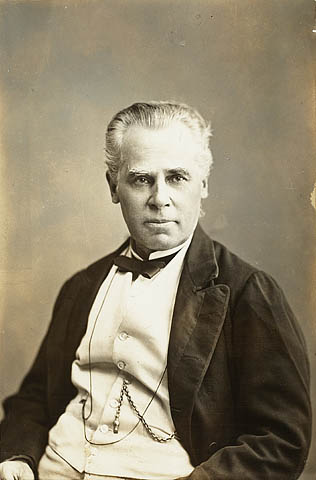

One possible solution was to replace the balancing of legislative seats between Canada East and West with representation by population. This approach was championed by George Brown. He was the powerful Reform Party leader in Canada West and editor of the prominent Globe newspaper. Under a “rep by pop” system, all voters would be treated equally. Where they lived or what language they spoke would not matter. Governments would reflect the wishes of the majority of voters in the whole united province.

Such an arrangement, however, was completely unacceptable to many French Canadians. Many believed rep by pop would reduce them to a minority in an expanding English-speaking, Protestant province. This could have potentially disastrous consequences for their religion, language and culture. The Reformers in Canada West insisted on individual rights. But this ran headlong into French Canadian determination to protect their collective rights.

Other Options

Another solution appealed to many Radicals (also called Clear Grits) in Canada West. It was simply to dissolve the union. English Canadians in Canada West could control their own affairs, as could French Canadians in Canada East. But this would leave vulnerable minorities in each territory: English-speakers in Canada East and Irish Catholics in Canada West. There was also the chance that dissolving the union would make the new provinces easier to annex into the United States. Not surprisingly, Britain opposed anything that might weaken its North American empire. British opposition to dissolving the union would be difficult to overcome.

A third option was to govern the province according to the principle of the “double majority.” This would require legislation to have the support of a majority in both Canada West and Canada East. But this would only work if each region elected like-minded majorities. That possibility was extremely unlikely.

George Brown's Federalism

Given the difficulties with these approaches, George Brown became increasingly drawn to the idea of a federal arrangement between Canada East and Canada West. This would involve the creation of two separate provinces. They would be linked by a new federal parliament. Brown also favoured expanding any federation to include the wilderness territory of Rupert’s Land. It was controlled at the time by the Hudson’s Bay Company.

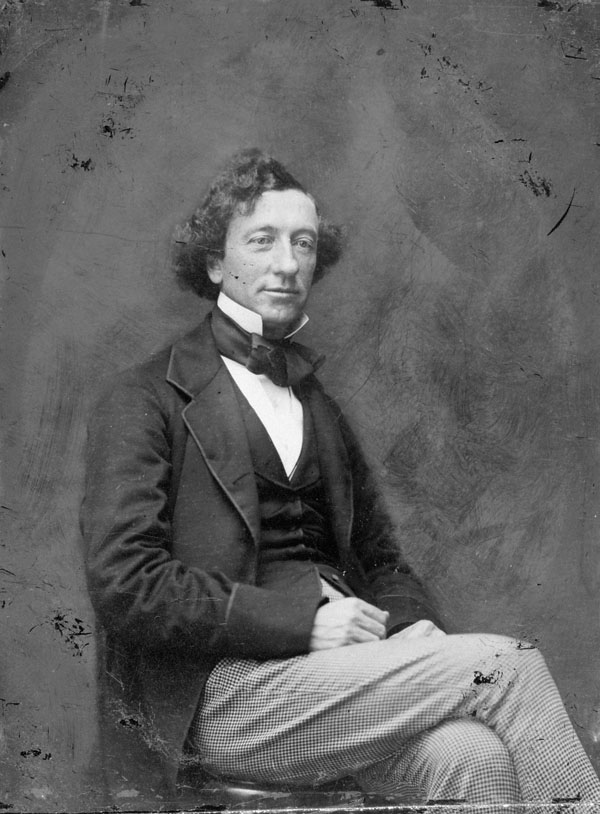

In 1860, Brown introduced the idea in the Province of Canada legislature. He got nowhere. Brown’s proposals were rejected by a decisive majority. In fact, they nearly split his own party. Most French-Canadian politicians saw no reason to change the status quo, which gave them the power they wanted. John A. Macdonald's Liberal Conservative coalition in Canada West remained in alliance with Conservative majorities in Canada East. As long as that was the case, Macdonald's supporters would be part of the government even if they were a political minority in Canada West.

In 1860, a federal union seemed dead in the water.

Towards the Great Coalition

Four years later, however, George Brown’s Reformers and John A. Macdonald's Liberal Conservatives in Canada West were working with George-Étienne Cartier's Parti bleu in Canada East. They all supported Confederation. It was one of the most remarkable and rapid transformations in Canadian political history. What had happened?

Part of the answer lies in external events. The biggest factor was the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861. As the war continued, the Union army expanded. Tensions between the US and Britain threatened to escalate into war. It came close to happening in the winter of 1861–62. Canada could not possibly stand up to American power without British support. But Britain believed Canada should play a larger role in defending itself. It felt that a united British North America would be more effective in this regard than a string of separate colonies.

Amid this pressure, Canadian politicians struggled to form strong, lasting governments. Between 1861 and 1864, there were two elections and a string of weak administrations. Something in the political system of the Province of Canada needed to change.

Meetings in the “Spirit of Compromise”

George Brown decided that drastic action was necessary. In October 1863, he publicly mused about creating an all-party committee to discuss Canada’s constitutional future. Everything would be on the table. The idea was to have an open, non-partisan discussion on ways to break the political logjam of Canadian politics.

Brown introduced his proposal in the legislature in May 1864. The Liberal Conservative government was clinging to power by its fingernails. Conservative leaders John A. Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier and Reformers such as Luther Holton and Antoine-Aimé Dorion opposed Brown’s resolution. But both the Conservative and Reform rank and file were divided on the question. To the surprise of Macdonald and Cartier, the resolution received enough cross-party support to pass.

Brown immediately appointed a committee of members drawn from both parties to discuss constitutional reform. At the first meeting, he locked the door and put the key in his pocket. “Now gentlemen,” he said, “you must talk about this matter, as you cannot leave this room without coming to me.” And so, 17 men, some of whom could not stand one another, were trapped in a room trying to find a way out of Canada’s constitutional difficulties. John A. Macdonald and Cartier were members of the committee, as were Holton and Dorion. Despite their personal and political differences, they approached their work, in Brown’s words, “frankly and in a spirit of compromise.”

During eight meetings, they discussed the merits and shortcomings of rep-by-pop, dissolution of the union, the double majority, federalism, and continuing the status quo. On 14 June 1864, Brown reported to the House that the committee had a “strong feeling… in favour of changes in the direction of a federative system, applied either to Canada alone or to the whole British North American Provinces.”

Later that day, the Liberal Conservative government was defeated in the House on an unrelated non-confidence motion. This would almost certainly mean yet another election, followed by yet another unstable government.

A New Alliance

Then something surprising happened. Brown believed the political crisis offered an opportunity to break the constitutional logjam. John A. Macdonald decided a political alliance with George Brown could open up all kinds of options. After a brief meeting between the two men on 16 June, the talks began.

In the negotiations that followed, the Liberal Conservatives insisted that Brown and his Reform supporters become part of a governing coalition rather than only offering informal support. The Liberal Conservatives believed that if Brown was actually in the Cabinet of the new government, he and his supporters would be easier to control. For this reason, Brown was reluctant to join a government with his old enemies. But he came under intense pressure from the Conservatives and his own supporters. They argued that he could best influence events from a position of power. Rather than risk the breakdown of negotiations, Brown decided that he and his party would come into the government.

Towards Confederation

The other question was whether a federal solution should apply only to the Province of Canada or to British North America in general. Brown preferred a federal arrangement for Canada alone. Such an arrangement would leave the Reformers in control of Canada West. Any attempt at a wider solution could detract from the urgent task of dealing with the Canada’s constitutional crisis.

John A. Macdonald had never liked the idea of limiting a federal arrangement to the two Canadas. He also believed a British North American settlement could counter the continental expansion of the United States. (See also: Manifest Destiny.) It could also broaden Macdonald’s Conservative base by bringing in the Maritimes. After four days of discussions, a compromise was reached. Legislation would be introduced in the next parliamentary session for federalism among the Canadas. In the meantime, the coalition government would explore the possibilities of a wider federal arrangement in British North America.

Charlottetown Conference

The Great Coalition was formed in late June 1864. That same week, the Governor General of the Province of Canada, Lord Monck, wrote to his counterpart in Nova Scotia. He requested that a Canadian delegation attend a conference on Maritime union that was already being planned in the colony of Prince Edward Island. The request was accepted.

Members of the Great Coalition joined government and opposition politicians from New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and PEI for the Charlottetown Conference in September 1864. The conference was, in the words of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, an “extraordinary armistice in party warfare.” It paved the way for Confederation in 1867.

The Great Coalition was a turning point in Canadian history. It proved remarkably successful in breaking the logjam of central Canadian politics and in helping to create a new country.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom