The language that children first acquire naturally in the home is known as their mother tongue. A careful distinction must be made between someone’s mother tongue and their first language. Someone’s mother tongue is the one they acquire in the very first years of childhood, as they are first acquiring language itself. One’s mother tongue can easily be lost or retained. If it is retained, then it becomes one’s first language. But if it is lost, it is replaced with what then becomes one’s first language (for example, if a child’s mother tongue is a minority language where the child lives, and the child ends up using the majority language instead — a process known as linguistic assimilation).

One’s first language is not necessarily the first language that someone acquires in their lifetime (it may be, in which case it is the same as their mother tongue, but that is not automatically the case). Rather, one’s first language is the first language that comes to one’s mind when one is speaking under the most spontaneous conditions possible. Thus one’s first language may vary over the major phases of the sociolinguistic trajectory of one’s lifetime.

Any language learned after the first language has been acquired is a second language. Most children appear to learn their mother tongue and their first language without any special instruction or formal teaching (nowadays, the loss of a language is no longer the subject of a formal or authoritarian intervention, but that was not always the case). Some linguists have attributed this facility to an innate, specific language-learning capacity; others believe it to be attributable to general cognitive capacities. Even in the first language, however, reading and writing must be taught, and thus first-language and second-language teaching and learning have much in common.

Languages in Canada

From a strictly legal standpoint, there are three major classes of languages in Canada: official or "Charter" languages — French and English — which are recognized under the federal Official Languages Actof 1969 (under provincial legislation, however, French is an official language only in Québec and New Brunswick); those that Statistics Canada terms “immigrant languages,” which enjoy no official status in Canada but that are spoken as national or regional languages elsewhere (see Ethnic Languages); and ancestral languages of Indigenous peoples, which are not protected legally at the federal level (see Aboriginal Languages in Canada).

Language issues of particular significance in Canada include the learning of French as a second language (FSL) by English-speaking Canadians and by immigrants to Québec; the learning of English as a second language (ESL) by francophones in Québec and by immigrants to English-speaking Canada; the maintenance of other languages, such as those spoken by immigrants and Indigenous people; and the learning of English or French as a second language by Indigenous people.

French as a Second Language

The great importance attached to the teaching of French reflects changes in the long history of francophone-anglophone relations. Until recently, because economic power was largely in the hands of anglophones, the French language did not enjoy the same status in Canada as English, despite the historical significance of French, its demographic significance, and the fact that French is one of the world's major languages. This was true even in Québec, where the vast majority of the population speaks French. In response to the discontent of francophone Quebecers with this situation, successive Québec governments since the 1960s have taken measures to protect the French language, culminating in legislation such as the Charte de la langue française (also known as Bill 101), which was passed to promote the use of the French language. Although French has made significant gains in this new environment, the relative positions of French and English remain a contentious issue in Québec (see Québec Language Policy).

In the early 1960s, some members of the English community of Saint-Lambert (the Saint-Lambert Bilingual School Study Group, in Québec), reacted to the evolving importance of French and to the isolation of the French and English communities from each other by questioning methods of FSL instruction in English schools. Searching for better methods, this group consulted Wallace Lambert of McGill University, who had studied the sociopsychological and cognitive aspects of bilingualism, and Wilder Penfield, founder of the Montreal Neurological Institute, who had studied brain mechanisms underlying language functions. At this group's initiative, an experimental kindergarten French-immersion program was established in Saint-Lambert in 1965. In this kind of program, participating children receive the same type of education they would receive in the regular English program, except that the material is all taught in French. The teachers are generally native speakers of French who understand English, and children are generally treated as though they, too, were native speakers. This historic experiment marked the beginning of certain modern trends in language instruction.

After a relatively slow start in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, enrolment in French-immersion programs increased almost tenfold between the late 1970s and 1999, reaching 300,000 students in some 2,000 schools. After that, there was a slow, gradual decline. According to Statistics Canada, from 2006 to 2011, the number of citizens who said that they could hold conversations in both of Canada’s official languages increased, to 5.8 million from about 350,000. As a result, the rate of French-English bilingualism in Canada rose from 17.4% of the population to 17.5%. Nevertheless, the acquisition of French as a second language, especially among young learners, remains extremely limited in Canada outside of Québec. Canadians age 15 to 19 have the highest rate of French-English bilingualism (in other words, young people who are in their final years of secondary school, when their involvement with language studies is greatest). But since 1999, bilingualism appears to have lost ground among members of this age group whose first official language spoken is English.

French-immersion programs are of three main types.

Early Total Immersion Programs

Early total immersion programs span up to 11 years and are divided into three phases: a monolingual phase (usually kindergarten to Grade 2 or 3) when all curriculum materials are presented in the second language but children may speak among themselves or to the teacher in English; a bilingual phase (usually Grade 2 or 3 to Grade 6) when English and French are used equally for instruction; and a maintenance phase (usually from Grade 7 to the end of secondary school) when 3 to 5 subjects are offered in French.

Delayed Immersion Programs

Delayed immersion programs are those in which the use of French as a major medium of instruction is delayed until the middle elementary grades (usually Grade 4).

Late Immersion Programs

Late immersion programs postpone intensive use of FSL until the end of primary school or the beginning of secondary school.

Immersion education, pioneered in Canada, is internationally recognized as one of the few successful experiments in second-language instruction. A distinguishing feature of this movement has been the active involvement of parents' groups across Canada. In 1977, a national association, Canadian Parents for French (CPF), was created to promote increased opportunities for FSL of all types. CPF has become a powerful lobby group at all levels of government.

Although enrolment in immersion programs has increased significantly over the years, a large majority of English-speaking students in elementary and secondary schools still learn French in the more traditional way, where it is taught as a subject and is not the medium of instruction. As of 1999, there were some 2,470,000 students enrolled in such programs across Canada. These programs are often referred to as Core French programs and have suffered from the popularity of immersion programs, which tended to get the better teachers assigned to them as well as much of the research funding available. The National Core French Study, a vast inquiry into the state of the teaching of French as a subject matter in Canada and the changes that might be needed to revamp it, addressed these concerns and made a number of recommendations that led to a renewed interest in Core French from the early 1990s on.

This renewed interest can be expected to grow over the years 2000 to 2020. In all of its documentation on the issue, the Canadian federal government expresses the firm intention of maintaining and strengthening the promotion and early teaching of each of Canada’s two official languages as a second language within the other official-language community.

English as a Second Language

If French language policies raise questions about Canadian unity and francophone-anglophone relations, the debate over English as a second language has been less political. For immigrants to English-speaking Canada, for example, learning English is a necessary prerequisite for economic survival. It was not until after the Second World War that provincial governments created language and citizenship programs for adult newcomers, that school boards established language classes for immigrant children, and that the growth of community colleges led to the development of post-secondary ESL programs. By the early 1970s, teachers of ESL had founded a number of provincial ESL associations, and in 1978, TESL Canada, a nationwide federation of associations involved in teaching ESL, was created.

No coherent national strategy concerned with the problems of immigrant adaptation has yet been formulated, and immigrant services are still provided by a complex network of school boards, universities and community colleges, and by agencies of the federal and provincial governments. Of particular significance in this area is the contribution to the difficult issues of language proficiency certification and standards of the LINC (Language Instruction for New Canadians) program. A wide variety of approaches has been developed to meet the needs of ESL students, but the field is beset by problems (which also beset FSL), such as insufficient numbers of teachers and consultants, inadequate teacher training, a paucity of appropriate curricula and materials, and the lack of clear goals.

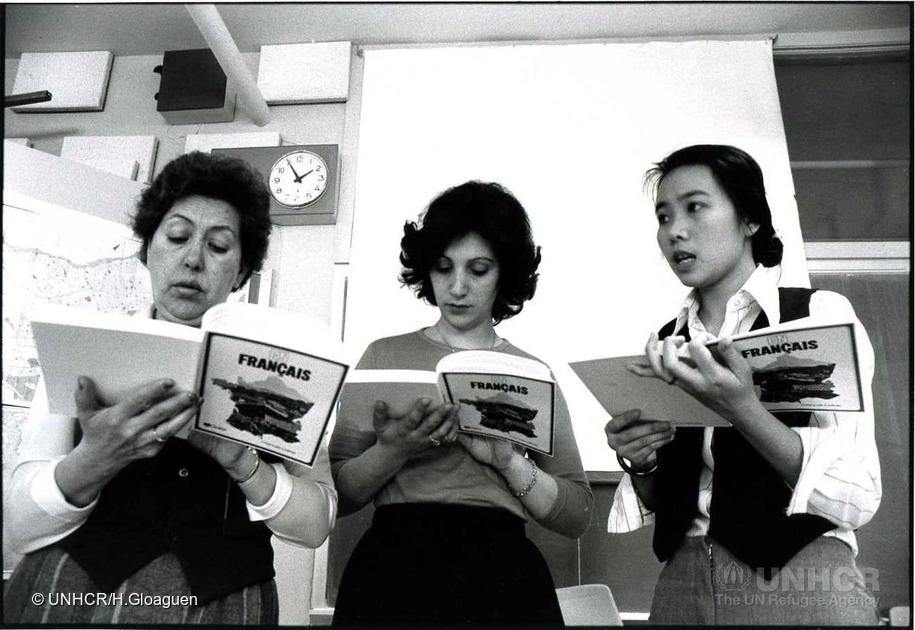

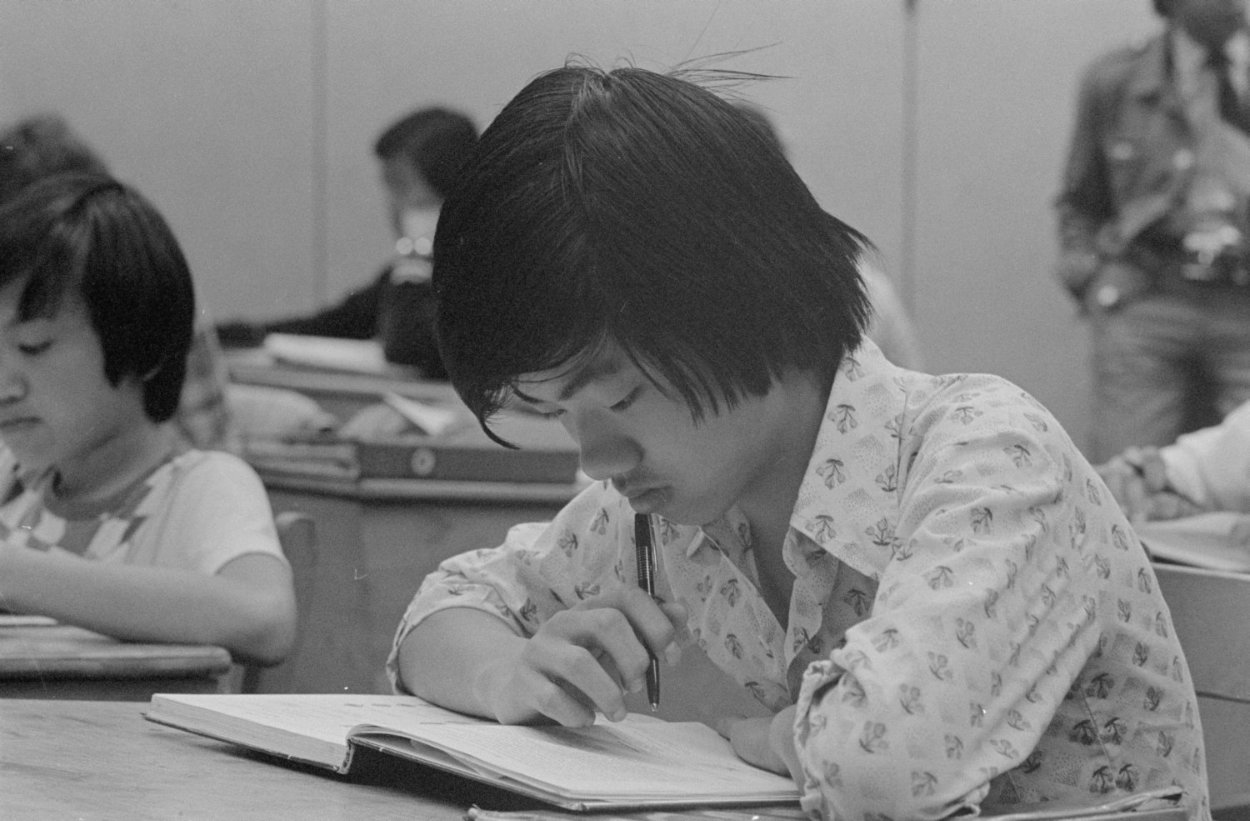

In the late 1970s, with the wave of refugees from Southeast Asia, the inadequacies of the language-training system and of settlement services became apparent. In 1981, after a national symposium on the problems of adult refugees, the TESL Canada Action Committee urged the development of a national policy of refugee settlement. The committee recommended a two-stage approach in which a basic three-month program would be followed by a variety of vocational options, with special provision being made for literacy training, for English in the workplace and English as a second dialect, and for special groups such as young adults, senior citizens, women and people in remote areas.

Federal Language-Training Program

Because any federal public service must be available in either official language, many federal public servants must be bilingual. The federal public service has established its own language-training program. During the 20-year span between the early 1970s and the early 1990s more than 2,500 public servants annually received language training in French or English in language centres across Canada. The last few years have been marked by a sharp reduction in the number of courses offered directly through federal language-training centres and a move toward subcontracting second-language courses to commercial language schools.

Teaching Methods

A century ago, the most popular method of second-language instruction was grammar translation, i.e., the teaching and practice of grammar rules through translation exercises. Around 1900, the moderately successful direct method was created. It involved teaching without translation and dispensing with the mother tongue completely in class. In the 1960s, the audiolingual method (i.e., speaking and listening in rapid drills) was popular. Since then, a number of new methods have been advocated. One of these emphasized the training of listening abilities through actions (total physical response), another the use of psychological relaxation (suggestopedia), and a third the use of techniques based on group therapy (counselling learning).

In the 1970s, other second-language instruction reformers suggested that more emphasis be placed on the curriculum and on the practical needs and specific purposes of language learners. There has been an accompanying attempt to ground second-language instruction more thoroughly in the language sciences, e.g., linguistics, psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics and applied linguistics. The most widely used teaching approach since the early 1980s is the communicative approach, where the objective is to have students use their second language in real-life communication situations. The concept of a project is often used in these approaches because the creation of a concrete product by students (the production of a game, for instance) puts them in a situation where language is used for communication, not as a subject matter.

This is not always easily accomplished, however, and new technologies have been recruited in the search for better instructional techniques. In the 1950s, the language laboratory was created; in the 1980s, microcomputers and videocassette recorders were commonly used as teaching and learning resources. More recently, the advent of multimedia and communication technology has opened seemingly new doors for language teachers and learners. It is believed that these new technologies could go a long way toward making learners more autonomous and better equipped for their language learning challenge. Although the use of such technologies is rapidly increasing, research data are still scarce, and it is not yet clear that any of these innovations will result in a radical breakthrough in second-language instruction.

Much more can probably be expected from developments in language-instruction practices in the first decade of the 21st century. These new trends accord central importance to differentiation, flexible teaching methods, and elimination of obstacles to the acquisition and expression of learning. Guided by the principle that students learn better when teaching activities are adapted to their own learning logic, contemporary language teachers take their learners’ cognitive, social, affective, and linguistic profiles as the starting point for all lesson planning. To adapt their teaching practices to the amply demonstrated contemporary linguistic diversity, language teachers in this decade apply teaching approaches, learning situations and other methods, interactive tools and differentiation devices that respond to it. For example, these teachers prefer to employ open questions and tasks that offer students multiple entry points, to use student-generated success criteria to assess learning, and to provide learning situations in workshop format alternating with sessions attended by the entire class and grouping of students around learning centres that call for multiple forms of intelligence.

As regards the acquisition of non-first languages, and in particular the teaching of English in francophone settings and French in anglophone settings, approaches that encourage language shock, even unintentionally, are avoided. Now instructors attempt to have the first and second languages co-exist without any tendency for one to supplant the other. Current language-instruction practices thus call for a teaching approach focused on developing additive bilingualism— that is, teaching the second language in a way that does not compromise the vitality and survival of the first but instead gives both of them a larger role (bilingualism without assimilation). Based on an updated, enhanced version of the communicative approach with an action-oriented perspective, current pedagogy places the accent first and foremost on developing oral-communication skills, conveying strategies for supporting them, and creating a learning environment that is characterized by empathy and mutual respect and hence lends itself to the risk-taking that is necessary for language development.

Maintenance of Non-official Languages

The 1963 Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism took the view that linguistic diversity is an important personal and social resource. In 1977, Ontario initiated its Heritage Languages Program, which provided funds for the teaching of "heritage" languages, i.e., languages other than English or French. Similar programs have been started in Québec, Manitoba, Alberta, British Columbia and the Northwest Territories.

Indigenous Languages

Linguists generally recognize 11 major groups of Indigenous languages in Canada, some of which contain a number of languages and dialects. Some Indigenous peoples (particularly in the North) have strongly retained their languages, but the medium of instruction in northern Indigenous schools is usually French or English (which most students must learn as a second language). Recently there has been a growing interest in developing ESL and FSL curriculum materials for Indigenous students and in conducting research into the conditions under which these students learn second languages. However, few teachers of Indigenous children have had second-language training, and appropriate methods of second-language instruction are not yet widely employed. Some bilingual education programs have been designed to maintain ancestral languages while allowing Indigenous children to acquire a knowledge of French or English. Here, as in other areas of second-language instruction, much still remains to be done in order to provide satisfactory programs.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom