Separatism refers to the advocacy of separation or secession by a group or people from a larger political unit to which it belongs. In modern times, separatism has frequently been identified with a desire for freedom from perceived colonial oppression. In Canada, it is a term commonly associated with various movements or parties in Québec since the 1960s, most notably the Parti Québécois and the Bloc Québécois. These parties have also used the terms "sovereignty," "sovereignty-association" and "independence" to describe their primary goal, although each of these concepts has a somewhat different meaning.

Confederation, Secessionism, and Defeat

The first full-fledged secessionist movement in Canada emerged in Nova Scotia shortly after Confederation in response to economic grievances, but it was quickly defeated. No other serious separatist force appeared in an English-speaking province for another century. In Québec, the Manifesto of the Patriotes in the Rebellions of 1837 had included a declaration that the province secede from Canada.

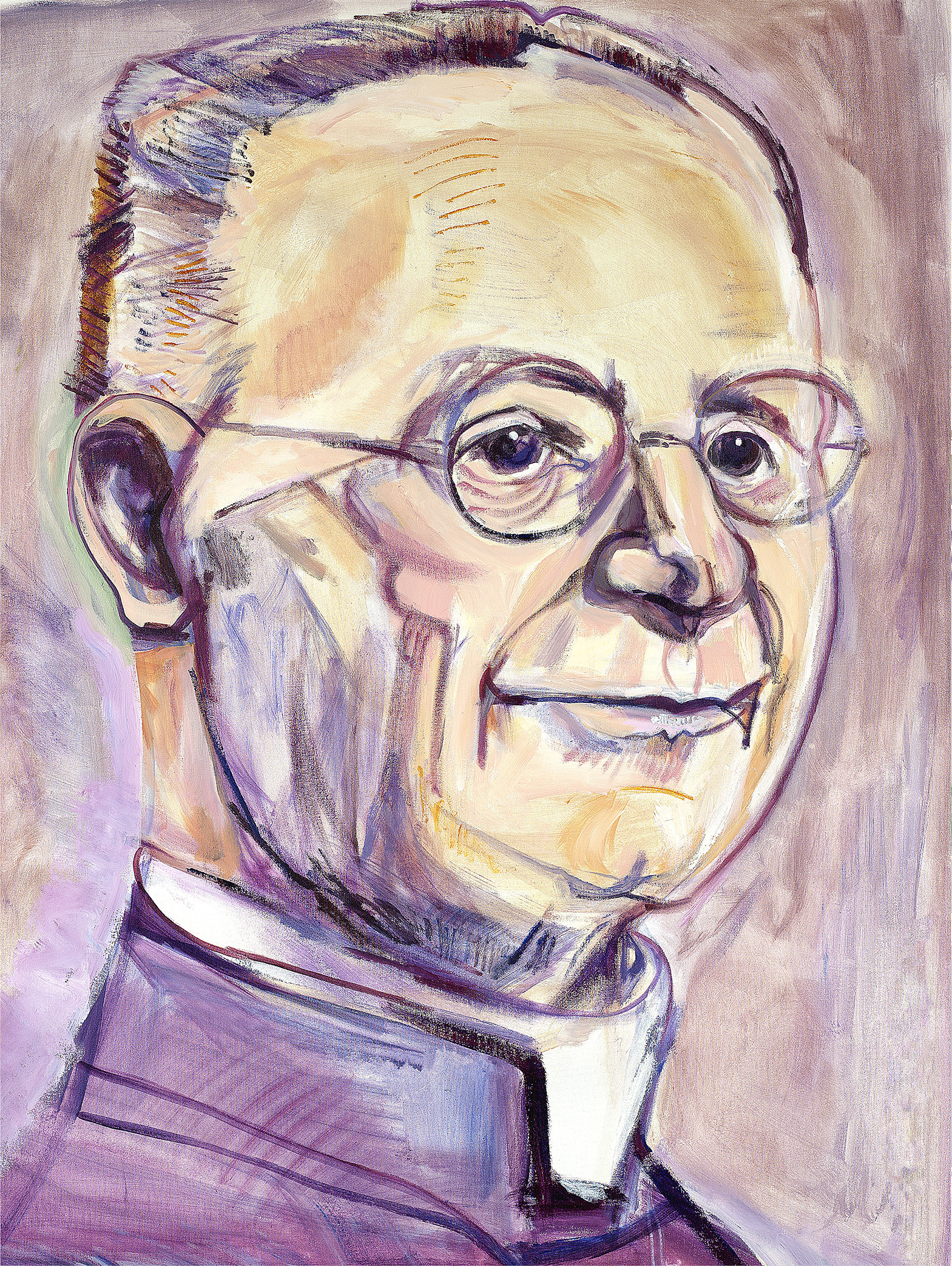

After the defeat of that rebellion (see Rebellion in Lower Canada), separatism no longer existed as a genuine component of the conservative French Canadian nationalism that emerged and was dominant for over a century in Québec. There were, however, isolated advocates of the doctrine of separatism. Notably, the journalist Jules-Paul Tardivel, in the late 19th century, and strong nationalists such as Abbé Lionel Groulx and his followers, in the early 1920s and mid-1930s, occasionally flirted with the idea.

Re-emergence

The separatist movement re-emerged as a political force in modern Québec in the late 1950s and the 1960s, a time of great socioeconomic change and nationalist foment in that province. The most important early manifestation of this rejuvenation was the leftist Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale (RIN). The RIN began as a citizens’ movement on 10 September 1960 and became a political party in March 1963. It first competed electorally in 1966, and together with other separatist groups garnered over 9% of the Québec vote. Some violent radical fringe movements committed to independence also operated during this decade, most notably the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), which attained notoriety in the October Crisis of 1970.

Popular support for separatism in Québec and for the organizations that represented it rapidly increased in the province in the late 1960s and the 1970s, particularly after the Parti Québécois was formed in 1968 (through the merger of the RIN and the Mouvement Souveraineté-association, or MSA, founded in 1967, and the RIN). Its founder and leader was the former broadcast journalist and Liberal Cabinet minister René Lévesque who was both popular and dynamic. The party was able to rally most of the province's nationalist political groups to its program of political independence coupled with economic association ("sovereignty-association") with English-speaking Canada.

Sovereignist Party Victory and Referendum Defeat

On 15 November 1976 the PQ swept to power with 41 per cent of the popular vote and 71 seats. It promised to delay any move toward independence until it had consulted the people of Québec in a referendum. In the Québec referendum campaign of 1980, the government of Québec asked the people for a mandate to negotiate sovereignty-association with the rest of Canada. Although this was only a mild expression of the independence option, it was decisively rejected on 20 May 1980 by about 60 per cent of the Québec electorate, including a majority of the French-speaking population. Some have attributed the defeat partly to a remark made by PQ minister for the status of women, Lise Payette, comparing female homemakers, who tended to support the “no” side, to a caricature of the submissive woman.

The PQ was nevertheless re-elected in 1981 on a program that included a promise to defer the independence question for at least another full term of office.

Patriation of the Constitution

While campaigning for the "no" side during the 1980 referendum, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau had promised Québecers he would renew the Canadian Constitution, which sets out the respective powers of the federal and provincial governments. This meant repatriating the British North America Act from Britain – or transferring it to the authority of the Canadian Parliament – and introducing a new constitution with a Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Two years later, when the new Constitution Act, 1982 was introduced – following months of heated negotiations on its terms by Ottawa and the provinces – Lévesque's PQ regime was the only provincial government not to have signed the deal, saying the terms were not acceptable to Québec. Although the new constitution still applied in the province, the absence of the Québec government's consent became a political sore that would fuel separatist sentiment there for years to come. (See Patriation of the Constitution.)

The matter would again come to a head in 1987, when a new Québec premier agreed to endorse an amended constitution under terms negotiated in the Meech Lake Accord. But the Accord's provisions failed to become law, the 1982 constitution remained, and since then, the Québec government has never given its formal consent to the constitution.

PQ Fortunes and the Bloc

Meanwhile in 1985, the PQ government's own popular support began to wane inside Québec – especially after the resignation of Lévesque that year. The PQ was defeated in the 1985 provincial election by the Liberals under the rejuvenated leadership of former premier Robert Bourassa, and languished in opposition for the rest of the decade. Support for full political independence remained around 40 per cent for most of that period.

The PQ regrouped in the late 1980s under the leadership of Jacques Parizeau, a former PQ finance minister, and its more radical sovereignist adherents. It pledged in its platform to declare Québec independence following a majority vote in a referendum on sovereignty. Immediately after the failure of the Meech Lake Accord in 1990, support for the sovereignty option increased significantly to about 65 per cent, but declined again to its more normal level of about 40 per cent after the PQ won a narrow victory in the provincial election of 1994.

In 1991, members of the Québec independence movement established a separatist political party at the federal level, the Bloc Québécois, under the leadership of a charismatic former federal PC Cabinet minister, Lucien Bouchard. It managed to win almost 50 per cent of the Québec vote and 52 seats in the federal election of 1993, and became the official opposition party in Ottawa. Its primary objective was to promote the separatist cause in national politics.

A Second Referendum

In October 1995 the PQ government organized another referendum on sovereignty (see Québec Referendum, 1995). It proposed to negotiating an economic partnership with English Canada following a majority vote in favour of sovereignty. About halfway through the campaign Premier Parizeau ceded his de facto leadership of the "yes" side to the more popular Bouchard. The sovereignists lost very narrowly in the October 30 referendum, 49.4 per cent to 50.6 per cent, but won a substantial majority among francophone voters. Parizeau resigned after shocking the general public by attributing the referendum defeat to “money and the ethnic vote.” He was replaced as premier by Lucien Bouchard.

During the initial period of his premiership, Bouchard made the elimination of the deficit and the strengthening of the Québec economy his major priorities. Pursuit of sovereignty was placed on the political backburner. At the same time, the federal government began to frame a coherent plan to combat future threats of Québec separatism.

Federal Response and Supreme Court Ruling

Prime Minister Chrétien appointed Stéphane Dion, an academic who was a strong opponent of Québec sovereignty, as his Intergovernmental Affairs Minister, and assigned him the responsibility of formulating this new strategy. Dion devised a two-pronged approach, which he characterized as "Plan A" and "Plan B." Plan A consisted of positive inducements and placating measures designed to win over francophone Québec public opinion to the federalist cause, such as the passage of a House of Commons resolution declaring Québec to be a "distinct society." Under Plan B, which consisted of more coercive measures, he directed his Ministry to frame a reference to the Supreme Court of Canada asking for its advisory opinion on the legality both under the Canadian constitution (domestically) and internationally of the unilateral secession of Québec from Canada. The Québec government refused to recognize the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court on this matter.

The Court handed down its ruling on this reference on 20 August 1998. It declared unanimously that under domestic and constitutional law, the Québec government could not initiate legal steps toward secession. However, faced with the consent of a clear majority of the Québec population on a clear question in a referendum (and the Court left the matter of defining what is meant by a "clear majority" and a "clear question" to the politicians), the federal government and the other provinces of Canada would be obliged to negotiate with the Québec authorities in good faith. The decision was viewed as a victory by both sides.

Clarity Bill

Dion subsequently drafted what became known as the "Clarity Bill" (Bill C-20). It defined the terms under which a "yes" vote in a referendum would be regarded as a "clear majority" on a "clear question." It would involve more than 50 per cent plus 1 (i.e. a simple majority), although the Clarity Bill did not specify the exact parameters of what would constitute a clear majority. The Clarity Bill was passed into law in June 2000.

Premier Bouchard was unable to mobilize increased support for the separatist cause, and this failure, and later internal criticism from the more "hard-line" separatist elements in his party, appear to have provoked his resignation as Québec premier and PQ party president in January 2001. He was succeeded by Bernard Landry, a long-time PQ leader, in March 2001. Since that time, despite his strong and clear reaffirmation of his commitment to Québec sovereignty, he has been unable to deliver on his promise. Support for Québec independence has dropped to about 40 per cent, its lowest point since the 1980 referendum.

Social Diversification of Independence Supporters

In its initial period of the 1970s, the modern form of separatism in Québec was particularly popular among the new middle classes, especially those linked to state structures and with aspirations in other expanding bureaucratic sectors of society. Its principal adherents, both within the rank and file and the leadership, continue to be liberal professionals (e.g. teachers, administrators and media specialists), white-collar workers and students 40 years later. There is also considerable support from trade union members, who form the core of its more radically nationalist and socially oriented adherents.

Since the 1980s, it has also garnered some support from the business sector, and from the traditional liberal professions, such as law and medicine. However, these latter groups continue to be more sympathetic to pan-Canadian political appeals, which are perceived to be more in tune with their economic interests. Moreover, a new generation of young francophones in their 20s and early 30s appear to be more open to global economic concerns, are more individualistic and economically conservative and do not appear to be as strongly attracted to separatist appeals as was the previous generation.

Thus far, given its support of French as the official language of Québec and the one that takes precedence in the province, the separatist cause has had very little success in its efforts to win votes among anglophones and allophones, who constitute slightly less than 20 per cent of the Québec population.

Political Diversification Following the Referendum

Since the PQ’s initial election victory in 1976, several political parties have emerged under the umbrella of the Québec independence movement.

The Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ) was the first new party to gain representation in the National Assembly. The party’s only seat was won by its leader, Mario Dumont. The ADQ was more right wing than the PQ, which is traditionally social democratic. Founded in 1994 by young dissidents of the Liberal Party of Québec (PLQ), the ADQ stood on the “yes” side of the referendum campaign of 1995. Subsequently, however, it offered a third option for the long term, one that lay between those of the PLQ and the PQ. In the 2007 provincial election, the ADQ enjoyed a brief moment of victory by winning 41 seats compared to the Liberal Party’s 48, thereby occupying the middle ground and playing a key strategic role in a minority government context. It lost its gains the following year, however, when it won a total of only seven seats in the election.

Québec solidaire (QS), a resolutely leftist independence party, is just as opposed to the ADQ as it is to the other main parties. Founded in 2006, it advocates for social justice and ecological questions as well as for sovereignty. However, the party won only one seat in 2008 and two in 2012.

Under the direction of former PQ minister François Legault, the leftist Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) absorbed the ADQ in 2011 and won 19 seats in the 2012 election. Despite its leader’s previous sovereignist leanings, the CAQ announced that it wanted to put all plans for a referendum on the back burner for 10 years and to concentrate on the economy. In 2012, Legault stated that he would vote against independence if there was a referendum in the near future.

Separatism in Western Canada

In English Canada in the early 1980s there was also some separatist activity, particularly in Alberta, which was embodied in the Western Canada Concept Party. The objectives of this party were to try to rectify perceived injustices in western Canada concerning such matters as freight rates, tariff barriers, oil pricing, bilingualism and western representation in the federal governing party, and failing that, to promote secession from Canada. However, the party failed to win much support, and succeeded in electing only one member in an Alberta provincial by-election.

Much of this support for western separatism has since dissipated, despite the emergence of a variety of parties such as the Western Block (founded in 2005) and the Separation Party of Alberta (founded in 2003), neither of which has been able to win seats in the provincial parliament. In fact, during the 2012 elections, the Separation Party won only 68 votes province-wide. Likewise, its neighbours to the east, the Western Independence Party and the Western Independence Party of Saskatchewan, have not made any significant gains in electorate support.

(See also: Confederation's Opponents)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom