Archivist Barbara M. Wilson explores the significance of a letter sent to Sir Sam Hughes by George Morton, a letter carrier, barber and civil rights advocate from Hamilton, Ontario. In his letter, dated 7 September 1915, Morton asked the minister of militia and defence why members of the Black community were being turned away when trying to enlist for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War. (See also Black Volunteers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.)

Ontario’s Black population had had a long association with the military forces in the province, some having been enrolled in the Kent County Militia as early as 1793 (see also Coloured Corps). It was evident in 1914, however, that Black volunteers were not welcome in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and Arthur Alexander of Buxton asked the Department of Militia and Defence for an explanation. He was told that “the selection… is entirely in the hands of Commanding Officers and their selections or rejections are not interfered with from Headquarters.” Alexander did not pursue the matter, but it was taken up less than a year later in a letter addressed to the Minister responsible, Sir Sam Hughes , on 7 September 1915 by George Morton of Hamilton. This letter, found in Library and Archives Canada (and included below), is a reminder of the desire to be involved in Canada’s expeditionary force.

Morton (1859–1927) was a letter carrier, a barber, and an early civil rights advocate. He was active in the District Lodge No 28 of the Grand Order of Oddfellows of Canada and had distinguished himself as a leader in the fight against segregated schools in the province. He also served as the treasurer for the local Letter Carriers’ Association and was the secretary for the Brotherly Union Society.

The baton was then passed to J.R.B. Whitney, publisher of the Canadian Observer, “The Official Organ for the Coloured People in Canada.” He offered to raise a unit of 150 Black soldiers in November 1915 and was told by Hughes “that these people can form a platoon in any Battalion, now. There is nothing in the world to stop them.” Hughes failed to mention that the platoon would have to be accepted by the commanding officer of an authorized battalion before it could be formed.

On the strength of Hughes’s letter, Whitney began his recruiting campaign in the pages of the Canadian Observer, but no commanding officer was willing to accept the platoon, and Whitney was told that “permission to recruit… cannot be granted.” An exasperated Whitney asked for reconsideration of his scheme as well as some explanation he might offer to the men who had already signified their willingness to enlist. Whitney wrote Sir Sam Hughes on 18 April 1916, asking that his platoon be “placed with some Battalion, otherwise there will be a great disappointment with the Race and ill feeling towards the Government,” but again he was unsuccessful.

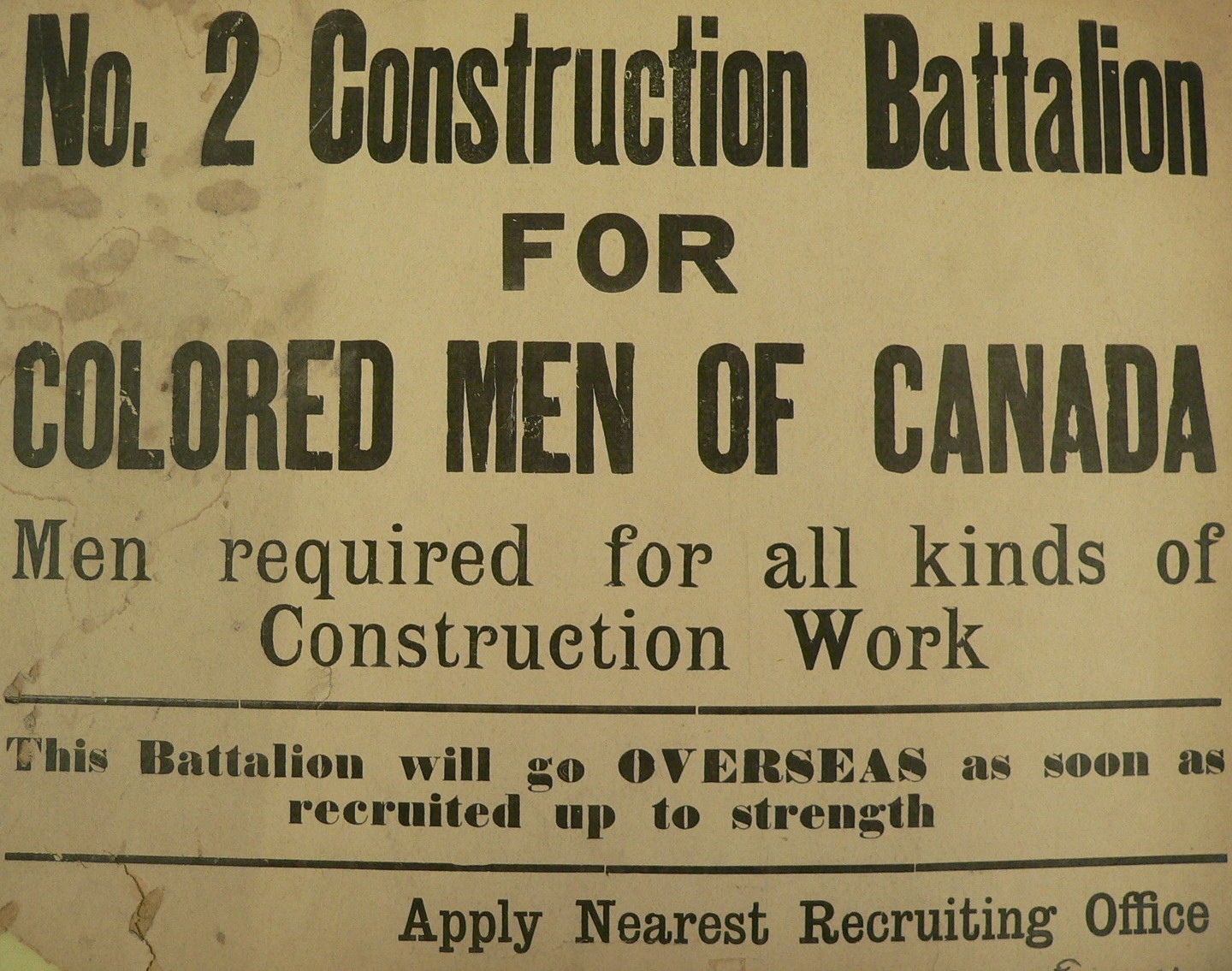

At the same time, General Willoughby Gwatkin suggested the formation of one or more Black labour battalions for service overseas. No. 2 Canadian Construction Battalion was authorized on 5 July 1916 after the War Office had cabled acceptance of such a unit. Headquarters were first in Pictou and later in Truro, Nova Scotia, and recruiting was conducted across the country. Only 71 recruits were obtained in Ontario, a figure somewhat below expectations and possibly attributable to the earlier rejection of a Black unit. In March 1917 it proceeded to Liverpool, England, and was later sent to France where it was attached to the Canadian Forestry Corps. (See also The No. 2 Construction Battalion and the Fight to Fight.)

George Morton To Sir Sam Hughes

52 Augusta St.,

Hamilton, Ont.

Sept. 7, 1915A Matter of vital importance to my People (the colored), in reference to their enlistment as soldiers, provokes this correspondence with you.

In behalf of my people I respectively desire to be informed as to whether your Department has any absolute rule, regulations or restrictions which prohibits, disallows or discriminates against the enlistment and enrolment of colored men of good character and physical fitness as soldiers?

And whether you as the well-qualified, popular and Honorable Head of said Department, have issued instructions to this effect, to your subordinates.

The reason for drawing your attention to this matter, and directly leading to the request of this information, is the fact that a number of coloured men in this city [Hamilton], who have offered for enlistment and service, have been turned down and refused, solely on the ground of color or complexioned distinction; this being the reason given on the rejection or refusal card issued by the recruiting officer.

Now among the recruiting officers here, in respect to this matter, there seems to be a difference and conflict of opinion. Some officers aver that there are no regulation orders or rules making such invidious discrimination and distinction.

A number of leading white citizens here, whose attention I have drawn to this matter, most emphatically repudiate the idea as being beneath the dignity of the Government to make racial or color distinction in an issue of this kind. They are firm in their opinion that no such prohibitive restrictions exist and have assured me they would very deeply deplore and depreciate the fact if it should turn out that such was in force and they have urged me to communicate with you as to the real existing facts.

Notwithstanding this kindly expressed opinion, there still remains this cold and unexplained fact that the proffered service of our people have been refused. Now our people feel most keenly this unenviable position in which they seem placed and they are very much perturbed and exercised over the matter as it now stands. The feeling prevails that in this so-called Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave that there should be no color lines drawn or discrimination made. As humble, but as loyal subjects of the King, trying to work out their own destiny, they think they should be permitted in common with other people to perform their part and do their share in this great conflict. Especially so when gratitude leads them to remember that this country was their only asylum and place of refuge in the dark days of American slavery and that here, on this consecrated soil, dedicated to equality, justice and freedom, that none dared to molest or to make them afraid.

So Our people, gratefully remembering their obligations in this respect, and for other potential reasons, are most anxious to serve their King and Country in this critical crisis in its history and they do not think they should be prevented from so doing on the ground of the hue of their skin.

If there are restrictive regulations as regards our peoples’ enlistment (which I trust there are not), a knowledge of this fact, unpleasant as it may be, will prevent them from further offering their services in the hour of their county’s need, only to suffer the humiliation of being refused solely on color lines.

It as your earliest opportunity you will honor me with a reply to the information herein asked for, I will deeply appreciate it.

In closing, permit me, Hon. Sir, in behalf of our people, to offer our humble congratulations to you on the recent signal honor so worthily conferred upon you by His Most Royal Majesty The King, for your distinguished services to the country.

This article first appeared in The Champlain Society online series Findings/Trouvailles, a regular feature that presents an intriguing piece of the Canadian past and illuminates its content and context. Through Findings/Trouvailles, The Champlain Society provides everyone with a passion for Canadian history a space to share their interest in the people and events of the past and to explain how these artifacts speak to them.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom