Alphonse Desjardins (1854-1920) of Lévis, Quebec, was disgusted when he realized how poorly banks treated people - all people, not just those with questionable solvency. He saw how difficult it was for the working classes to make a go of it. In 1897, upon learning about loan-sharking, he resolved to fight back on behalf of the working poor, to tell the big banks - the Emperors of Finance - that enough was enough. Desjardins had been born into a poor family and was highly motivated to fight usury, improve conditions for the working classes and give French Canadians economic liberation.

On December 6, 1900, after three years of study, discussion and communication with supporters of mutualism and economic cooperation in Quebec and Europe, Desjardins founded the Caisse Populaire, the People's Bank, in Lévis. It was the first successful credit union in North America, and was designed to "serve the humblest classes" and develop "honesty, industrious habits, good conduct and thrift." Within ten years, Desjardins had opened 100 caisses in Quebec. At the time of his death, he had earned an international reputation as an authority on collective financial institutions. He won honors from countries around the world but he derived the greatest pleasure from the designation "Caisses populaires Desjardins."

Credit unions were part of the 19th-century cooperative movement that grew out of the industrial revolution. As organizations grew and began to dominate people's daily lives, co-operatives, or co-ops, appeared to be a means of regaining control. Co-ops are owned and managed by their clients and exist in three types: retail co-operatives; producer co-operatives, such as grain pools or fish canneries; and credit unions, which now offer a full range of banking services to their members. Co-op members, as shareholders, have a democratic voice in the operation of the organization and receive part of the profits.

The world's first credit unions were established as "mutual self-help societies" and as "a strong moral and spiritual force." Robert Owen established the first consumer co-operative among unemployed weavers in Rochdale, England in 1844. At the same time, Germany experimented with applying co-operative principles of buying and selling to borrowing and lending. Despite the success of the Caisse Populaire in Quebec, the institution was accepted slowly in other parts of Canada. In the 1920's, attempts to establish credit unions in Western Canada and English-speaking Ontario failed.

|

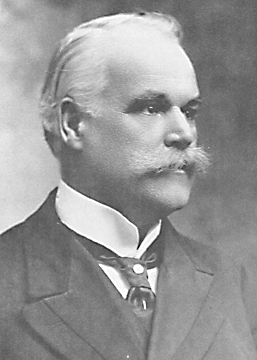

| The caisse populaire, founded by Alphonse Desjardins was established in 1900 as a co-operative savings and loan company with nonfixed capital and limited liability (courtesy La Société historique Alphonse Desjardins). |

In the 1930's organizers of the Antigonish Movement allied themselves with the Credit Union National Association, an American organization, and established a credit union in Broad Cove, NS. The Antigonish Movement was sponsored by the extension department of St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, NS. The movement promoted social and economic change through adult education. Movement members established community forums to study, and develop a clear understanding of, an area's strengths and problems and ways to control its economics. They initiated co-ops to overcome difficulties and develop economic opportunities. For example, Father James Tompkins, vice president of St Francis Xavier, initiated a goat-breeding co-op in Canso, NS to relieve the community's dependence on fishing, its only industry, and its reliance on outside help.

Credit Unions spread rapidly throughout Atlantic Canada. By the early 1940's, they were being established in English Canada; in Saskatchewan the CCF government actively encouraged their formation. To improve credit unions' efficiency, leaders of credit unions in the English-speaking provinces established provincial centrals, distinguishing them from caisses populaires. During the 1950's and 60's credit unions grew rapidly, using member savings to provide mortgages and short-term loans. They competed effectively with banks because of low overhead and convenient hours. At the same time, they acquired the legal right to offer most of the same financial services as banks.

Members of credit unions usually have some sort of common characteristic; they belong to the same ethnic group, church organization or trade union; they have the same profession; or they come from the same geographic area. Credit unions continued to grow until the recession of early 1980's, when western credit-granting institutions were hit particularly hard. Credit unions saw their asset values decline along with the general collapse in property values. Provincial governments were required to step in to help maintain solvency.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom