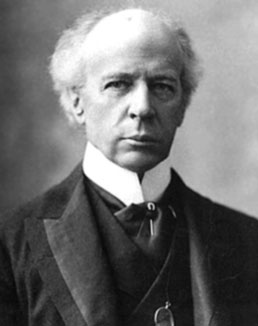

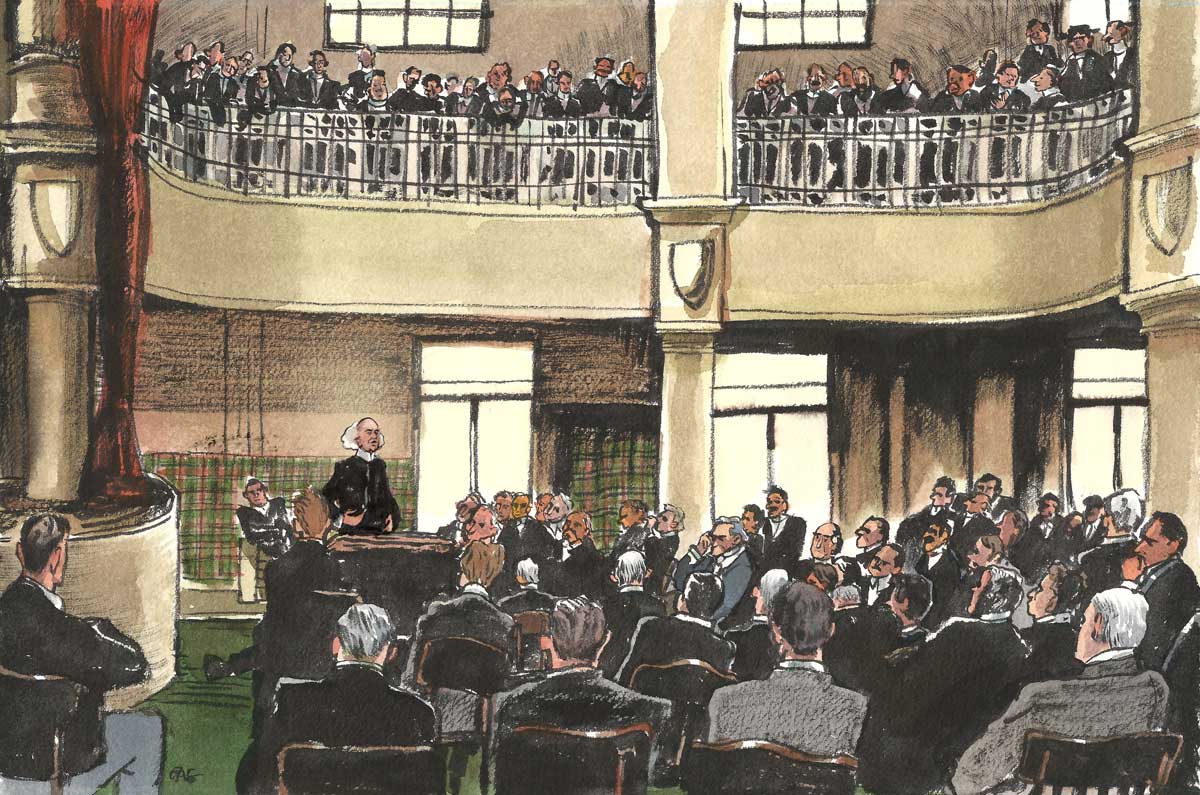

There is something distinctly Canadian about the fact that the author of a famously bold prediction about his country’s future was originally opposed to its creation. “All the signs point this way,” Sir Wilfrid Laurier told an adoring crowd at Toronto’s Massey Hall on 14 October 1904: “the 20th century shall be the century of Canada and Canadian development.” It was a claim he made more than once that year, and when he said those words, Laurier was in his 60s, frail in health but sure in his views, a political icon who had eight years of experience as prime minister, and a life filled with achievements, frustrations, turnabouts, and more than a few triumphs. He was a long way in every way from the young man who, almost four decades earlier, had been a political radical who once called Confederation “the tomb of the French race and the ruin of Lower Canada [Québec].”

In many ways, Laurier mirrored the evolution of the country he served as its first-ever francophone prime minister. He overcame the shared suspicion between the country’s two founding linguistic groups, as he came to believe each was stronger together than apart (see Francophone-Anglophone Relations). He realized that for Canada to flourish, it would need newcomers from other countries and cultures, so he encouraged immigration (although he blotted his copybook in 1911 by supporting efforts to suppress immigration to Canada by Black people). He preserved Canada’s independence by resisting efforts to draw it closer into the sphere of a powerful friend (Great Britain). And he deftly played the interests of Britain and the United States against each other in order to be friends with both — without becoming more beholden to either. He was one of Canada’s first proponents of free trade with the United States — although in that he was too far ahead of his time — which led to his 1911 electoral defeat.

An eloquent speaker open to compromise but sure of his views, the paradox of Laurier was that he professed little interest in political leadership. “I know I have no aptitude for it,” he said when he was chosen leader in 1887, “and I have a sad apprehension that it must end in disaster.” In fact, he had similarly taken his time getting into elected politics, and even longer in deciding to temper his relatively radical early views as well as his initial dismay at the prospect of a large, unified Canada.

But by the time Laurier got up in front of his Massey Hall audience that night, he was sure of his convictions and forward-looking in his view. Far from looking back, he looked ahead, focusing on all the strengths he foresaw for Canada in the future. In fact, he aimed many of his remarks specifically — and unusually — at the 20-somethings in the crowd, rather than older voters. He told them he expected that in their lifetimes, they would see the country’s population rise from its then total of 6 million people to “at least 40 millions.” At a time when many people were instinctively suspicious of outsiders — at least those who were not British — he forecast that “Canada shall be the star towards which all men who love progress and freedom shall come.” Along with Clifford Sifton, he had already implemented steps in favour of immigration that led to the West becoming one of the economic engines of Canada’s growth.

Laurier’s buoyancy that night is particularly striking, measured against the challenges and hardships that still lay ahead. His party was almost destroyed in the 1911 federal election, when his opponents turned his support of free trade against him and accused him of plotting the destruction of Canada. From there, now in his 70s, he worked desperately to rebuild the Liberals even as the country plunged into the First World War. In 1917, he ran — and lost — again, and died two years later (see Election of 1917).

But even as Laurier’s final years belied the hope and cheer he expressed in 1904, a longer-term look shows he was far more right than not. Throughout the 20th century, Canada’s two major language groups continued — for the most part — to get along. Immigration became a cornerstone of the country’s growth. Canada increasingly asserted its independence from Britain and, of course, finally achieved Laurier’s free trade objective with the United States. His Liberal Party, which appeared on the edge of collapse near the end of his life, rebounded to dominate Canadian politics for much of the century. And his beloved Canada, while it never attained the level of achievement he forecast, continued to grow and prosper, becoming the destination point of dreams for millions of people around the globe. In his goals and ambitions, Canada was a country always looking beyond itself, seeking continually to improve. Much like Sir Wilfrid Laurier — the man who did so much to set it on that track.

Excerpted from Canada Always by Arthur Milnes. Copyright © 2016 by Arthur Milnes. Published by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom