Overdoses from a class of painkiller drugs called opioids are claiming the lives of thousands of Canadians from all walks of life. The death count is the result of an escalating public health crisis: an epidemic of opioid addiction. The crisis is made deadlier by an influx of illicit fentanyl and chemically similar drugs, but it can be traced to the medical over-prescribing of opioids, including oxycodone, fentanyl and morphine.

Worsening Crisis

More than 15,000 people died of opioid-related deaths in Canada between January 2016 and December 2019 — an average of more than 10 a day. Ninety-one per cent of those deaths were accidental. Seventy-seven per cent of accidental opioid-related deaths involved fentanyl or a fentanyl analogue in 2019, compared to 55 per cent in 2016. Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid that is being cut into a growing number of street drugs.

No province has been hit as hard as British Columbia, which declared a state of emergency in 2016. Fentanyl was detected in 85 per cent of the 979 illicit-drug overdose deaths in that province in 2019, compared to 67 per cent in 2016. On any given day, firefighters — usually first on the scene of a medical call — respond to multiple overdoses. Of recent years, 2017 and 2018 saw the highest number of illicit-drug overdose deaths in BC. The 979 deaths in 2019 marked a 37 per cent decreased from 2018 (in which there were 1,546 deaths) and a lower total than 2016. However, the death toll began climbing again during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. From May to July 2020 alone, BC recorded more than 500 illicit-drug-related deaths.

Did you know?

Experts suggest several reasons for the rise in opioid-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. Street drugs became more potent and toxic as border closures disrupted supply chains and local dealers began cutting drugs with more additives. Pandemic precautions also played a role, as social distancing and reduced capacity at safe consumption sites left more people using drugs alone. Finally, some people turned to drugs to cope with the mental health impacts of the pandemic.

In Alberta, the community of Stand Off on the Blood Tribe reserve has endured a disproportionate number of deaths. Esther Tailfeathers, a family physician from the Blood Tribe, responded to her first fentanyl overdose in July 2014. At first, she treated one or two overdose cases a week in her hometown of 12,800, but that quickly escalated to two or three a shift. The local band council declared a state of emergency in March 2015, making Blood Tribe the first community in the country to sound the alarm because of fentanyl. Shortly after, the epicentre of Alberta’s crisis shifted to Calgary as fentanyl use began to skyrocket in the city. In 2019, Calgary and Edmonton accounted for about 75 per cent of the province’s 523 fentanyl-related deaths. For the province as a whole, accidental fentanyl-related deaths in 2019 were 51 per cent higher in 2019 than in 2016.

The scourge of fentanyl rapidly expanded east, becoming the leading cause of opioid deaths in Ontario for the first time in 2014. Between 2000 and 2015, nearly 6,300 people died from overdoses related to opioids in Ontario. Opioids claimed more than half that number (3,605 lives) in the three years that followed.

Roots of the Epidemic

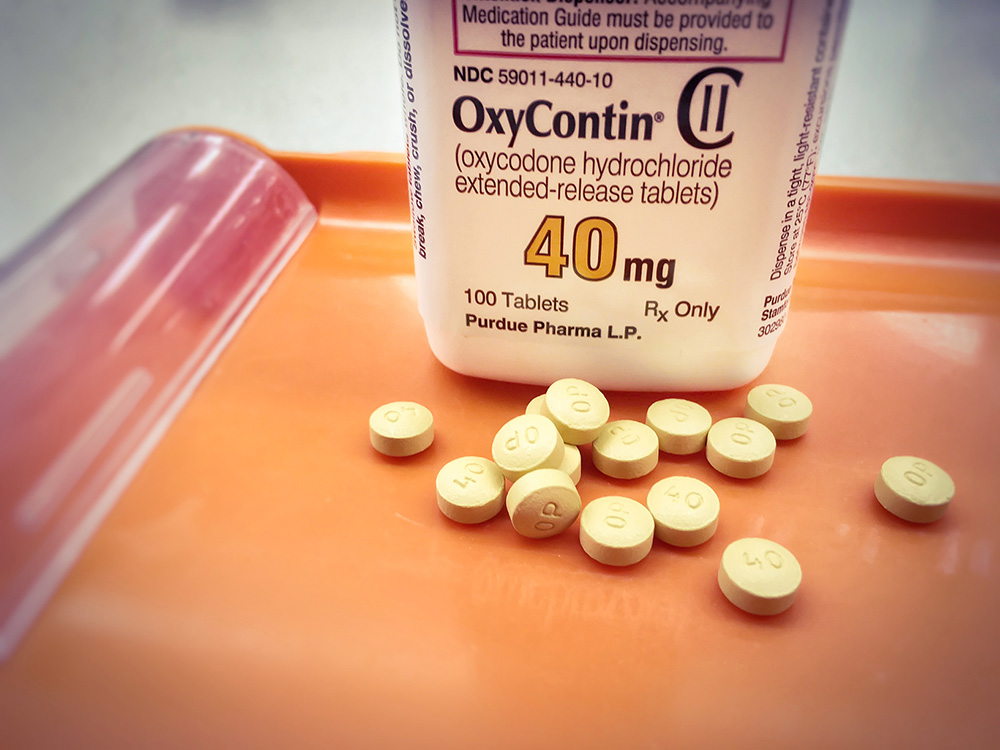

Canada is dealing with the fallout from a decision in 1996 to make opioids more widely available. Until then, doctors prescribed opioids primarily for terminal cancer patients. But in 1996, Health Canada approved OxyContin, a brand-name version of the opioid oxycodone, to relieve moderate-to-severe pain in all types of patients, heralding a sea change in the treatment of pain.

Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, distinguished the drug from its rivals by promoting its time-release formula — the pill was designed to be swallowed and digested over 12 hours. Sales representatives at the company persuaded doctors to expand their use of opioids by pushing the notion that OxyContin posed a lower risk of abuse and dependence to patients than other, faster-acting painkillers.

Doctors started prescribing OxyContin for everything from backaches to fibromyalgia (a syndrome that affects muscles and soft tissue, causing chronic pain, fatigue and sleep problems). The blockbuster drug became the most popular, long-acting painkiller in Canada for more than a decade. But it also became a lightning rod in the early 2000s, as reports of addiction and overdoses exploded.

Alternative Opioids Prescribed

Purdue pulled OxyContin from the market in 2012 — shortly before the patent expired — and replaced it with OxyNEO, a tamper-resistant alternative that is difficult to crush, snort or inject. Around the same time, the provinces all but stopped paying for OxyContin and OxyNEO through their public drug plans. But by focusing their response on just those two drugs, medical experts say, policy-makers missed the larger picture. Doctors began prescribing alternative opioid painkillers, including fentanyl, to their patients. As a result, prescriptions continued to climb in Canada.

In 2016, doctors wrote one prescription for every two Canadians, making the country the world’s second-biggest per-capita consumer of pharmaceutical opioids after the United States. The rate of opioid prescription is decreasing in Canada, but the epidemic remains a public health crisis.

New Class of People Who Use Drugs

The widespread use of prescription opioids is behind the rise of a new class of people who use drugs. Many people who were prescribed the highly addictive pills became dependent on them, unable to break their habit and requiring stronger and stronger doses.

OxyContin was popular not only with people who became addicted after their doctors prescribed it, but also with those who used heroin. Both groups could easily snort it like cocaine or inject it like heroin for a quick high. With OxyContin no longer available, many people turned to the black market to feed their addiction. Organized crime exploited the demand for a replacement for OxyContin with a counterfeit version of the drug, fueling a sharp spike in accidental overdoses.

Burgeoning Black Market

Police made their first big bust of a Canadian operation dedicated to producing and selling industrial quantities of illegal bootleg fentanyl in April 2013, shortly after OxyContin disappeared from the market. Police in Montreal arrested two men operating the drug-dealing operation on their way to a UPS courier store to ship a microwave oven containing 10,180 fentanyl tablets to New Jersey. The two men pleaded guilty and were each sentenced to about eight years in prison in 2014.

Since then, police have busted traffickers in almost every province. But the Montreal case was uncharted territory — three officers became ill after kicking in the door of the clandestine lab churning out the toxic, bootleg pills, including one who spent the night in hospital.

Prescription-grade fentanyl, developed in 1959 by a Belgian chemist and adopted as a pain reliever in hospitals, came into widespread use in the mid-1990s with the introduction of the transdermal patch that is worn like a bandage and releases the drug into the patient’s bloodstream over 72 hours. It is up to 100 times more powerful than morphine. When fentanyl is processed in a clandestine lab with no quality controls, it is difficult to get the dosage right, making it potentially more dangerous and leading to an unprecedented surge in deaths.

Gaps at the Border

China’s chemicals industry has helped foster the market for illicit fentanyl in Canada. Chemical companies in China custom-design variants of pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl by tweaking a molecule ever so slightly. A few hundred micrograms — the weight of a single grain of salt — are enough to trigger heroin-like bliss. One of the best-known fentanyl analogues is alphamethyl fentanyl, known on the streets as China White. Drug dealers smuggle the white crystalline powder into Canada from China and dilute the potency by cutting it with powdered sugar, baby powder or antihistamines before it is sold on the street. The dealers often put the mixture through a pill-press machine to produce tablets, dye them green to mimic the 80-milligram OxyContin pills favoured by people addicted to opioids, and sell them as “greenies” or “shady eighties.”

Fentanyl and many chemically similar opioids are classified as controlled substances in Canada, making them illegal to import without a license. But online suppliers shipping drugs to Canada devise clever ways to skirt inspection rules. Suppliers often ship drugs in packages weighing less than 30 grams, which used to ensure that border agents could not legally open them. In May 2017, agents received the authority to search — without the consent of the recipient — international packages weighing less than 30 grams that arrive through the mail and by courier. Many suppliers offer guaranteed re-shipment to customers in the event their package is intercepted at the Canadian border.

Potent Money Maker

Fentanyl has revolutionized the illegal drug trade in Canada. Unlike the massive infrastructure and cartels required to manufacture and transport heroin or cocaine, just about anyone can buy and sell fentanyl. Because it is so powerful, a little goes a long way, making it highly profitable for traffickers. A kilogram of powder — an amount equal in weight to a medium-sized cantaloupe — purchased over the internet for as little as $12,500, sells on the street for $20 million. A kilogram is enough to produce one million tablets, which sell for $20 each in major cities.

Lag in Government Response

Canadians have been dying from accidental opioid overdoses for nearly two decades. But the response from government leaders has lagged well behind the mounting problem, a legacy of the tough-on-crime policies of Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s Conservative government (2006–15). As a result, until recently, Canada lacked a national surveillance system to track fatal overdoses. Outdated information in many regions hindered the emergency response to a rapidly evolving situation, according to medical experts. Moreover, people who use drugs have faced various barriers to accessing addiction treatment programs.

Instead of devoting resources to treatment programs and harm-reduction measures, such as the provision of the overdose antidote naloxone, the Harper government fought a war on drugs, mainly by prosecuting low-level offenders. Any mention of harm reduction was removed from Health Canada’s website in 2007, when the federal department changed the name of its National Drug Strategy to the National Anti-Drug Strategy.

The federal government also attempted to shut down Insite, North America’s first supervised injection site in Vancouver’s impoverished Downtown Eastside. Insite allows people addicted to drugs to safely consume illegal drugs under a nurse’s supervision. The Conservative government eventually lost that battle at the Supreme Court, which in 2011 ordered it to allow Insite to remain open. The government responded to the ruling by introducing legislation making it difficult, if not impossible, for other sites to open.

New Approach

The Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau abandoned its predecessor’s criminal justice approach and reframed the opioid crisis as a public health issue. In December 2016, the government replaced the Conservatives’ National Anti-Drug Strategy with the new Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy. The Liberals’ then-health minister Jane Philpott, a medical doctor, pledged to “reinstate harm reduction as a key pillar in this strategy.”

One of Philpott’s first initiatives was to have Health Canada change the status of the overdose antidote naloxone to a non-prescription drug, making it more widely available. During a national conference on opioids in November 2016 — the first time the federal government brought policy-makers and medical experts together to come up with strategies to address the topic — the health minister vowed to use every tool at her disposal to address the “national public health crisis.”

In December 2016, the government unveiled legislation in the House of Commons aimed at curtailing Canada’s booming underground market in fentanyl. Bill C-37, which became law in May 2017, bans pill press machines from being imported into Canada, and it gives border guards who inspect goods coming into the country broader powers to seize and open suspect packages weighing less than 30 grams. The law also reduces barriers to opening and operating supervised drug-consumption sites like Insite.

In an effort to counter a surging number of overdose deaths, and following years of work by harm-reduction activists, the federal government approved a rapid expansion of supervised injection sites. As of June 2020, there were nine approved sites in British Columbia; seven in Alberta; one in Saskatchewan; 22 in Ontario; and four in Quebec.

Responding to the spike in overdose deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, BC introduced a new safe-supply program. The federal government funded two new safe-supply sites in Toronto. These efforts aimed to increase access to safer, prescription alternatives to street drugs. During the pandemic, Dr. Bonnie Henry, Premier John Horgan, the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police and harm reduction advocates called on the federal government to decriminalize possession of illegal drugs for personal use.

Addressing the Roots of the Crisis

In addition to harm-reduction measures such as the supervised injection sites, medical experts say more needs to be done to address the roots of the opioid crisis: the overprescribing of a drug whose risks are substantial and benefits uncertain. McMaster University received funding from Health Canada in 2015 to develop new national guidelines for safely prescribing opioids. But shortly after the guidelines were released in May 2017, Jane Philpott, health minister at the time, ordered an independent review to ensure that they were not “tainted” by industry influence.

Dr. Philpott’s intervention followed revelations that officials at McMaster did not honour a pledge to exclude medical experts who receive income from pharmaceutical companies from voting on the guidelines. A family doctor who was on the 15-member voting panel had been a paid speaker and advisory board member for drug companies, including Purdue Pharma — a fact that did not come to light until 8 May 2017, the day the guidelines were published.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the federal agency asked to conduct the review, concluded in a report issued on 7 September 2017 that the development of the new guidelines was “scientifically rigorous despite the flaw in promptly identifying the [conflict of interest] in a single voting member.” The research institute blamed an “administrative oversight” for the fact that the doctor’s conflict of interest was not identified at the beginning of the process. Had it been identified earlier, the review says, McMaster officials overseeing the guidelines would have excluded the doctor from the voting panel.

Legal Fallout

Many people living with substance abuse were first introduced to opioids by their family doctor. But all too often, the stigma associated with opioid addiction leads them to suffer in silence, aware that society tends to blame the victim and view their problem as a character weakness.

Many of them have also waged a long legal battle with Purdue. In April 2017, the maker of OxyContin agreed to pay $20 million to settle a long-standing class-action lawsuit representing as many as 1,500 Canadians who got hooked on the drug after their doctors prescribed it. The lawsuit accuses the company of knowing that anyone who took the drug would be at risk of becoming addicted to it, but at no time were these risks disclosed. The nature and scope of Purdue’s deceit did not become publicly known until 2007, when the company and three of its executives paid $634.5 million (US) to settle criminal and civil charges against them in the United States for misbranding the drug as less addictive than other pain medications. Purdue’s Canadian operation has not admitted any wrongdoing.

The proposed national settlement in Canada was approved by courts in Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia (see Court System of Canada). It had to be also approved in Saskatchewan in order to pass. The settlement was stalled by a Saskatchewan court that was not satisfied the settlement was “fair, reasonable and in the best interests of the class as a whole.” The lawsuit is not an admission of liability by Purdue. Medical experts said the compensation amounts to little more than a rounding error for a company that amassed revenues of $31 billion (US) from OxyContin.

In addition to the civil lawsuit, the Ontario government asked Ottawa to prosecute Purdue under the criminal provisions of Canada’s Food and Drugs Act (FDA) for what Ontario’s health minister called “inappropriate or potentially illegal activities in the marketing of OxyContin in Canada.”

In August 2018, the British Columbia government launched a lawsuit to sue over 40 opioid manufacturers, including Purdue Pharma. The government alleges the companies contributed to the crisis by downplaying the risks their drugs posed when marketing them to doctors for some 20 years. Though a dollar amount was not specified, the government sought to recover provincial health care costs associated with the overdose crisis, including addiction treatment, emergency response and hospital expenses caused by the “negligence and corruption” of drug companies. The suit marked the first time that a province sued drug companies over the opioid crisis. Several other provinces have since joined the suit, which also targets retailers such as Shoppers Drug Mart and the Jean Coutu Group, as well as distributors and wholesalers. In September 2019, Purdue filed for bankruptcy in the US as part of a settlement of similar suits from governments in that country. Purdue has claimed that its Canadian entity is a separate company that is not directly affected by the US proceedings.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom