This article is one of four that surveys the history of the film industry in Canada. The entire series includes: Canadian Film History: 1896 to 1938; Canadian Film History: 1939 to 1973; Canadian Film History: 1974 to Present; Canadian Film History: Regional Cinema and Auteurs, 1980 to Present.

See also: Quebec Film History: 1896 to 1969; Quebec Film History: 1970 to 1989;

Quebec Film History: 1990 to Present; 30 Key Events in Canadian Film History;

Exhibit Eh: Canadian Film History in 10 Easy Steps; Documentary Film; Canadian Film Animation;

Experimental Film; Film Distribution; Top 10 Canadian Films of All Time;

English Canadian Films: Why No One Sees Them; National Film Board of Canada;

Telefilm Canada; Canadian Feature Films; Film Education;

Film Festivals; Film Censorship; Film Cooperatives;

Cinémathèque Québécoise; The Craft of Motion Picture Making.

The National Film Board of Canada

One of the most significant events in Canadian film history was the establishment of the National Film Board of Canada (NFB). In 1938, the federal government commissioned Scottish filmmaker John Grierson to study the state of film production in Canada. Grierson had coined the term “documentary.” He was also head of the Empire Marketing Board and the General Post Office in Britain. He wrote a report that year that led to the creation of the NFB in May 1939. He was named the Board’s first film commissioner in October 1939.

The NFB was originally designed as an advisory board to coordinate the production of films. But the demands of the Second World War led to a shift towards active production. This involved absorbing the Government Motion Picture Bureau in 1941.

By 1945, the NFB had grown into one of the world’s largest film studios. It had a staff of nearly 800 people based in Ottawa. More than 500 films had been released. These included the propaganda series Canada Carries On (1940–59) and The World in Action (1942–45). These were shown monthly in Canadian and foreign theatres. An animation unit had been set up under the supervision of Scottish-born filmmaker Norman McLaren. Non-theatrical distribution circuits were established. Many young Canadian filmmakers were being trained.

The NFB became a leading producer of world-class documentaries, animation and experimental films. Its productions have won more than 5,000 international awards, including a dozen Academy Awards. But its creation did little to solve the problem posed by the dominance of American films in Canada.

Canadian Cooperation Project

By 1947, there were two large theatre chains in Canada: Famous Players and Odeon Theatres. N.L. Nathanson, the founder of Famous Players, left the company to form the rival Odeon chain with his son, Paul. The two chains controlled roughly two-thirds of the theatrical market in Canada. Odeon was later sold to the Rank Organization of England, Britain’s largest vertically integrated film company. Both of the major exhibition chains in Canada were therefore foreign-owned. This had two main consequences for the Canadian industry. First, Canadian-produced films were virtually frozen out of their own market. And second, most of the theatrical revenue (about $17–20 million annually) went to the US.

After the Second World War, Canada, like many countries, experienced a balance of payments problem with the US. As a result, in 1947, the federal government restricted imports on a large number of goods. Money made on films was discussed. There was talk that a quota system could be introduced for Canadian films (similar to the radio quota for Canadian music that was introduced in the early 1970s). Forcing Hollywood to invest part of its box-office profits in Canada was also a major talking point. In February that year, Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) leader M.J. Coldwell proposed in the House of Commons that the federal government impose a protective tariff on Hollywood films exhibited in Canada. Later that year, Liberal Finance Minister Douglas Abbott met with Famous Players and the CMPDA. Douglas asked them to voluntarily invest some of their box-office profits from the Canadian exhibition market in Canadian production facilities.

But the president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), Eric Johnston, intervened. He instead proposed what became known as the Canadian Cooperation Project. It was approved by the Liberal government of Louis St-Laurent in 1948. The Hollywood film lobby agreed to shoot some of their films on location in Canada, include favourable references to Canada in Hollywood movies to promote tourism, and encourage the distribution and exhibition of NFB films in the US. All of this would be in exchange for the uninterrupted flow of dollars out of Canada.

The nationalistic lobbying on behalf of Canadians was successfully defeated. Famous Players’ profits were not restricted. The idea of an exhibition quota for Canadian-produced films was dropped. A multi-million-dollar film studio under development in Vancouver was also shuttered. The NFB, which had lobbied for fiscal restrictions on Hollywood money, was also thwarted. The distribution of NFB films in the US did not increase. Several Hollywood films — such as Canadian Pacific (1949), Saskatchewan (1954) and generic B-movies like Canadian Mounties vs. Atomic Invaders (1953) — were shot and/or set in Canada. American tourism into Canada actually decreased during the first four years of the project. It only increased by 15 per cent from 1948 to 1958, compared to a 130 per cent increase from all other countries.

By 1957, the balance of payments problem was no longer an issue and the protective tariff no longer a threat. The project was quietly terminated in 1958. After St-Laurent retired from politics, he became a member on the board of directors of Famous Players Canadian Corporation.

Private Production Begins, 1947–67

The Canadian Cooperation Project helps to explain why, during the 1940s and 1950s, there was virtually no feature film production in Canada outside of Quebec. ( See also: Quebec Film History: 1896 to 1969.) However, thanks to the economic boom in Canada following the Second World War, a number of small, independent producers began to establish themselves, making primarily industrial films and shorts. In 1941, Nat Taylor founded the trade magazine Canadian Film Weekly. In recognition of the nascent private film sector, the Canadian Film Awards were established in 1949. (The Canadian Film Awards became the Genie Awards in 1980. They then merged with the Gemini Awards in 2012 to become the Canadian Screen Awards.) The inaugural presentation was held in Ottawa. Crawley Films of Ottawa won the first Film of the Year Award for the short film, The Loon’s Necklace (1949).

In a gesture to the industry in 1954, a 50 per cent capital cost allowance (CCA) was introduced by the federal government. This was to encourage private investment in Canadian film companies. About a half-dozen English feature films were made in the late 1950s. Sir Tyrone Guthrie, who was instrumental in establishing the Stratford Shakespeare Festival, directed a production of Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex (1956) starring Douglas Campbell, William Hutt and Douglas Rain. A young CBC writer, Sidney Furie, directed two low-budget films of considerable promise that dealt with young people rebelling against society. Both A Dangerous Age (1957) and A Cool Sound from Hell (1959) attracted international critical attention, especially in Britain. However, the neglect the films suffered in Canada persuaded Furie to emigrate to Britain in 1960. (He told the British press, “I wanted to start a Canadian film industry, but nobody cared.”) Furie was typical of the emigration of English-speaking filmmaking talent from Canada at the time. The impressive list of directors who left to pursue careers elsewhere includes Norman Jewison, Arthur Hiller and Ted Kotcheff.

While the development of feature filmmaking in Canada was still sputtering, pioneering work was being done at the NFB. By the late 1950s, Norman McLaren had won eight Canadian Film Awards, two major prizes at the Berlin International Film Festival, an Academy Award for his short film Neighbours (1952) and an Oscar nomination for A Chairy Tale (1957). The Board’s Unit B was putting out work of consistent quality. The Candid Eye series was producing groundbreaking direct cinema films. (See also: Documentary Film.)

In the realm of features, the 1960s started in much the same way as the previous decade had ended — with middling, occasional productions. One of these, The Mask (1961; a.k.a. The Eyes of Hell), was the first Canadian film picked up for US distribution. It employed the fashionable 3-D format. However, times were about to change. A new optimism was apparent. Ottawa filmmaker and producer F.R. “Budge” Crawley turned his limitless energies towards features and produced René Bonnière’s Amanita Pestilens (1963). It featured the big screen debut by French Canadian actor Geneviève Bujold. It was also the first Canadian feature filmed in colour and the first to be shot simultaneously in English and French. However, it was never released theatrically in Canada. The following year, Crawley had a modest hit with Irvin Kershner’s The Luck of Ginger Coffey. It was the gritty story of an immigrant writer (Robert Shaw) making his way in Montreal.

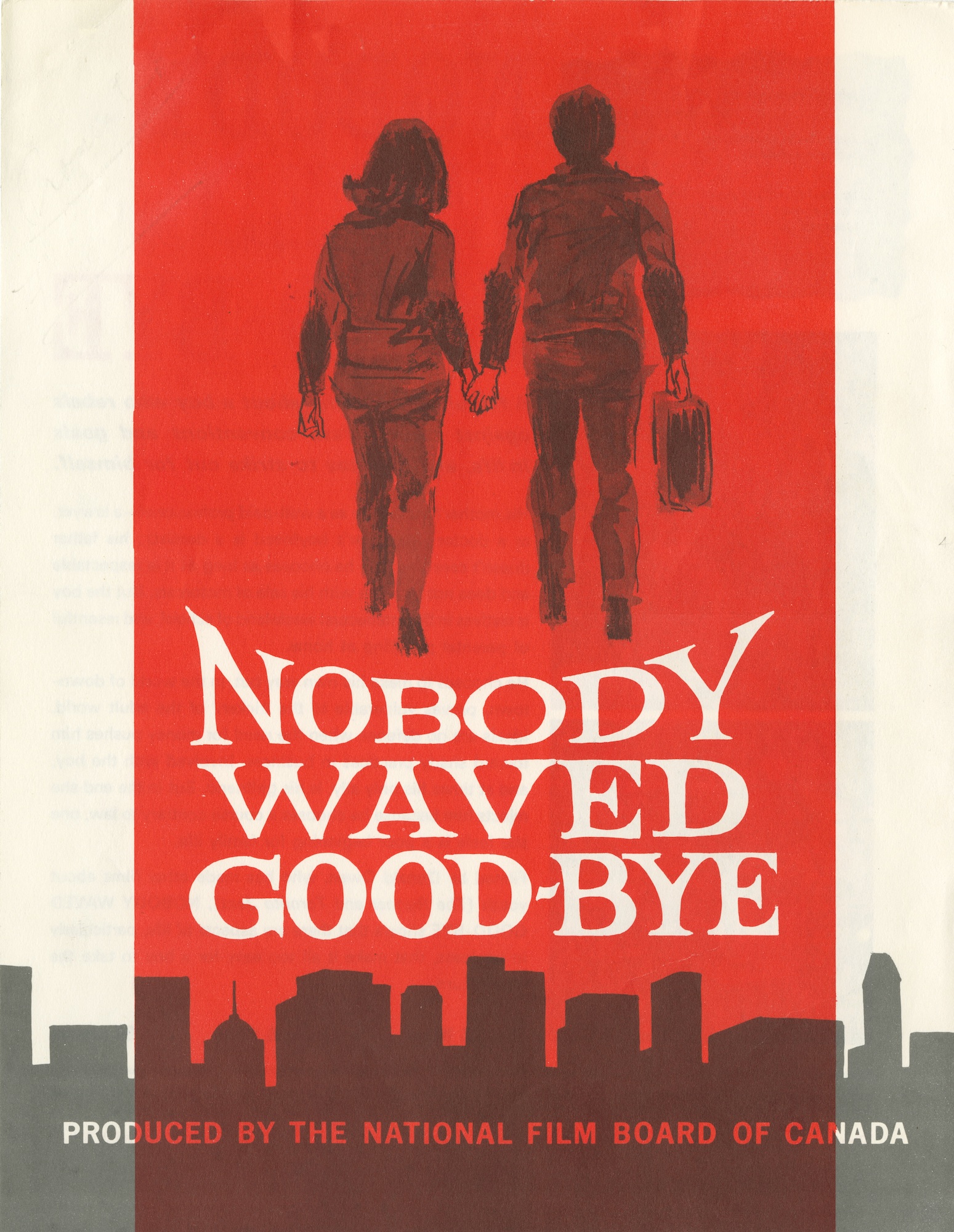

The NFB still primarily focused on documentary films, short subjects and animation. However, it also produced two English-language features in the early 1960s that were a harbinger of things to come. Drylanders (1963) turned to history for its subject matter. Nobody Waved Goodbye (1964), directed by Don Owen, explored the ennui of two suburban teenagers. Shot in the suburbs and streets of downtown Toronto, the film was financed by the NFB as a short docudrama but was clandestinely expanded into an improvised feature. Panned by Canadian critics upon its initial release, it gained new life when it became a critical darling at the New York Film Festival.

The late 1950s and early 1960s also saw the rise of cinema in Quebec. Emboldened by the creation of a French production branch at the NFB and the relocation of the Board from Ottawa to Montreal, the boom in television production in Quebec and technological innovations being made to production equipment, filmmakers such as Pierre Perrault, Gilles Carle, Claude Jutra, Michel Brault, Gilles Groulx, and Denys Arcand produced works of tremendous importance to the Quiet Revolution and the development of direct cinema. Feature films also began to emerge — namely Groulx’s Le Chat dans le sac (1964) and Carle’s La Vie heureuse de Léopold Z. (1965) — that were heralded as the first fiction films to truly speak to the Québécois experience. (See also: Quebec Film History: 1896 to 1969.)

Production throughout Canada also began to flourish in other ways. The aesthetic advances made by the French “New Wave” led to a more “personalist” cinema. The development of cheap, mobile 16mm cameras allowed more access to a medium that had previously been the preserve of a few. A number of low-budget features were produced across the country, mainly on university campuses. The Bitter Ash (1963), the first film made by Larry Kent while he was studying theatre at the University of British Columbia, created the most controversy. The sex scenes in the film turned it into an overnight sensation. Kent went on to direct two more features on the West Coast before moving to Montreal.

Many other student features were made, some by directors who continued to work in the industry, such as David Secter (Winter Kept Us Warm, 1965), John Hosfess (The Columbus of Sex, 1969) and Jack Darcus (Great Coups of History, 1968). An important figure during this period was David Cronenberg. Inspired by his classmate Secter, Cronenberg made two experimental, futuristic short films — Transfer (1966) and From the Drain (1967) — as a student at the University of Toronto in the late 1960s. He also helped found the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre before turning his talents to commercial production.

The Canadian Film Development Corporation, 1967

By 1967, a viable, emerging industry was beginning to produce critically acclaimed films. English and French filmmakers looked to government to protect their fledgling interests. The federal government took a significant step towards investing in a domestic industry by creating the Canadian Film Development Corporation (CFDC, now Telefilm Canada). It was initially funded with $10 million. However, the CFDC only concerned itself with production. It did not attempt to break the stranglehold American interests had over Canadian commercial distribution or exhibition.

At first, the CFDC gave money to some of the student filmmakers. Many of the subsequent films were artistic and commercial failures. A few attempts to imitate American models of filmmaking were supported, but with a similar lack of success. However, three films indicated more successful future directions. Television director Paul Almond, without CFDC money, directed Isabel (1968), a story set in the Gaspé starring his then-wife Geneviève Bujold. After several well-received documentaries, Toronto filmmaker Don Shebib directed the landmark docudrama Goin’ Down the Road (1970). It was an artistic and commercial success. It received national and international distribution and attracted large audiences. (It is still widely considered one of the Top 10 Canadian films of all time.) After honing his craft on numerous NFB documentaries and the groundbreaking À tout prendre, Claude Jutra directed the acclaimed Mon oncle Antoine (1971). It is still regarded by many as one of the greatest Canadian films ever made.

These films were unmistakably Canadian, using regional landscapes and characters with sensitivity and insight. They were followed by a number of richly observed films, such as Almond’s Act of the Heart (1970), Clarke Mackay’s The Only Thing You Know (1971), William Fruet’s Wedding in White (1972), Peter Carter’s The Rowdyman (1972), Peter Pearson’s Paperback Hero (1973), Paul Lynch’s The Hard Part Begins (1973) and Frank Vitale’s Montreal Main (1973). The first fiction feature made by a woman, Sylvia Spring’s Madeleine Is ... (1971), was made on the West Coast during this vibrant period.

All of these films were made on modest budgets. Only a few enjoyed modest commercial success. The CFDC was pressured to raise the visibility of the films it was funding, either by legislating the marketplace to guarantee the distribution and exhibition of Canadian films, or by employing foreign talent alongside Canadians. The Ontario Ministry of Industry and Tourism appointed broadcasting executive John Bassett to head a task force to study the Canadian film industry. The conclusion of the Bassett Report was that “a basic film industry exists. It’s the audiences that need to be nurtured through theatrical exposure. The optimum method of accomplishing this is to establish a quota system for theatres.”

In 1973, a group calling itself the Council of Canadian Filmmakers petitioned the Ontario government, urging it to follow the recommendation of the Bassett Report. Instead, in 1975, Secretary of State Hugh Faulkner negotiated a voluntary quota agreement with both Famous Players and Odeon Theatres. The chains were to guarantee a minimum of four weeks per theatre per year to Canadian films, and invest a minimum of $1.7 million in their production. Compliance with the quota was lukewarm at best. Within two years any semblance of it had evaporated.

This article is one of four that surveys the history of the film industry in Canada. The entire series includes: Canadian Film History: 1896 to 1938; Canadian Film History: 1939 to 1973; Canadian Film History: 1974 to Present; Canadian Film History: Regional Cinema and Auteurs, 1980 to Present.

See also: Quebec Film History: 1896 to 1969; Quebec Film History: 1970 to 1989; Quebec Film History: 1990 to Present; 30 Key Events in Canadian Film History; Exhibit Eh: Canadian Film History in 10 Easy Steps; Documentary Film; Canadian Film Animation; Experimental Film; Film Distribution; Top 10 Canadian Films of All Time; English Canadian Films: Why No One Sees Them; National Film Board of Canada; Telefilm Canada; Canadian Feature Films; Film Education; Film Festivals; Film Censorship; Film Cooperatives; Cinémathèque Québécoise; The Craft of Motion Picture Making.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom