Elzéar Bédard, lawyer, judge, politician, mayor, Patriote (born 24 July 1799 in Québec, Lower Canada; died 11 August 1849 in Montréal, Canada East). The son of a famous French Canadian political figure, Pierre-Stanislas, Elzéar Bédard had a distinguished career. Trained as a lawyer, Bédard joined politics in the 1830s and was one of the Parti patriote’s most moderate elements. He also helped resuscitate his father’s former newspaper, Le Canadien, and was the very first mayor of Québec City. In 1836, Bédard was appointed a judge of the Court of King’s Bench for the District of Québec, where he was embroiled in a controversy that cost him his post.

Early Life and Career

Born on 24 July 1799 in Québec City, Elzéar Bédard was the second-eldest son of Pierre-Stanislas, the former leader of the first political party in Canadian history, the Parti canadien. Bédard often followed in his father’s footstep: he attended the Petit Séminaire de Québec, studied law after graduation, and got involved in provincial politics, joining the party his father had led, the Parti patriote (known as the Parti canadien until 1826). However, his first foray into politics was unsuccessful; he was defeated in the 1830 general election in the riding of Kamouraska.

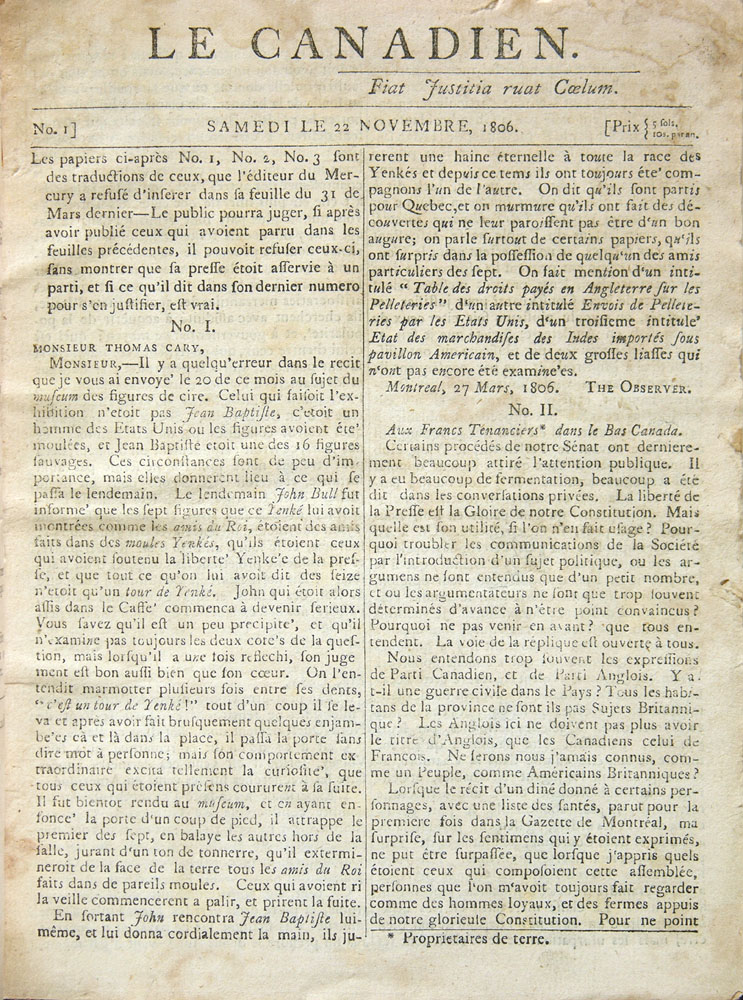

In 1831, Elzéar and four other individuals, including Étienne Parent, resuscitated his father’s newspaper, Le Canadien. The newspaper was first shut down in 1810 after his father and several staff members were arrested and their offices seized by government officials. Now under the editorial guidance of Parent, the newspaper continued where it left off: it educated French Canadians on their constitutional rights, fought for the preservation of their language, institutions, and laws, and promoted the aims of the French Canadian majority in the Assembly (see French Canadian Nationalism)

Parti Patriote and Municipal Politics

In 1832, Elzéar Bédard finally gained a seat in the Legislative Assembly when he replaced Philippe Panet (see Panet Family), by acclamation, as the representative for Montmorency. He retained his seat in the 1832 general election that soon followed. Though Bédard sided with the Parti patriote, historians have argued that he was generally against the party’s radicalism. For instance, though he was present when Louis-Joseph Papineau, Augustin-Norbert Morin and Louis Bourdages produced the 92 Resolutions — they were written at Bédard’s home — some historians and contemporaries have questioned Bédard’s enthusiasm for the resolutions. According to Michel Bibaud, the first French Canadian credited with writing a history of French Canada, Bédard barely had anything positive to say about the resolutions.

Bédard was one of the more moderate members of the party, and according to historian Claude Vachon, Bédard was the leader of a moderate wing called the Québec Party. This faction heavily criticized the party’s growing radicalism and sought a less hostile relationship with Governor Lord Gosford.

Bédard was also involved in municipal politics. In April 1833, he was elected, by acclamation, to the first city council for Québec as the councillor for the ward of Saint-Louis. A few days later, he was appointed as the first mayor of Québec City by his fellow councilmen, a position he kept until March 1834. Bédard held both offices — municipal and legislative — simultaneously. During this period, it was not uncommon for politicians to hold both. He left municipal politics in April 1835.

Habeas Corpus Controversy

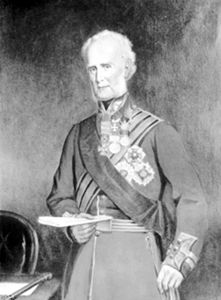

In February 1836, Elzéar Bédard left the Parti patriote when he accepted an appointment as judge of the Court of King’s Bench for the District of Québec. To many of his adversaries — radical members of the Parti patriote — taking the position meant that he had sold out and accepted a bribe from the Governor General, Lord Gosford.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Habeas Corpus Act was passed in England in 1679 and continues to apply in most of the countries ruled by common law. The writ of habeas corpus, short for the Latin phrase “habeas corpus ad subjiciendum” (which means “you shall produce the body [of the person concerned] to undergo [what the court may award]”) affirms the fundamental right of a person under arrest to be brought in front of a judge. In Canada, this principle is reaffirmed in Section 10 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982).

Bédard soon found himself at the center of a controversy. Following the 1837 rebellion in Lower Canada, the British government put in place a Special Council to govern the colony. In 1838, it passed one of its most controversial measures, an ordinance that suspended habeas corpusin the colony. Issuing writs of habeas corpusis an English legal practice. The writ requires that a person under arrest be brought in front of a judge, who must either formally charge the prisoner or release him or her. The purpose is to prevent individuals from being imprisoned without trial and unlawfully.The ordinance became a source of contention when two French Canadian judges, Philippe Panet and Bédard, issued a writ of habeas corpuson behalf of John Teed. A tailor from Québec City, Teed had been imprisoned under suspicion of high treason. Convinced that he was imprisoned without proper evidence, and consequently illegally, the two judges asked that a writ of habeas corpus be issued. In doing so, both judges disregarded the council’s authority. Following their demand to issue Teed a writ of habeas corpus, both were called before the Solicitor General to explain their decision.

To Bédard, the ordinance was unconstitutional: the Special Council did not have the authority to pass ordinances that modified the laws and constitution of the colony. Only the Imperial Parliament had the right to restrict or suspend the practice. He added that imperial laws, such as habeas corpus, emanated from a “sovereign authority” and had to be followed to the letter, not only by the colony’s judges, but by all local councils and assemblies, including the Special Council. If he obeyed the will of the council, he would disobey the laws of the empire itself. The governor general in power at the time, John Colborne, did not agree with their reasoning. He declared the ordinance legal and removed both judges from their positions on 10 December 1838.

The ordinance and the dismissal of two French Canadian judges caused quite a controversy in the colony, with newspaper editors, including Étienne Parent and Napoléon Aubin, and key political figures, such as Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine and Charles Mondelet, heavily condemning it and the Governor’s actions.

Later Life

Following his dismissal, Elzéar Bédard travelled to England to further explain his position. In 1840, he was reappointed to his post as judge, following the nomination of Charles Edward Poulett Thomson, who was sent to British North America to replace John Colborne as governor. Bédard remained in office until he died in August 1849 at the hands of, according to Vachon, “the last cholera epidemic in Lower Canada.”

Though Bédard may not remembered by many, he remains an important figure in Canadian history: he was the very first mayor of Québec, the leader of the moderate wing of the Parti patriote, and played an active role in the resuscitation of colony’s most important French-language newspaper. The 92 Resolutions were even produced at his home. More importantly, at a time when French Canadians lost all political representation and were at the mercy of the Special Council, he provided a voice of opposition when it threatened one of their most basic rights.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom