Located in the southern United States, the state of Louisiana has a population of 4,533,372 according to the 2010 census. Louisiana’s history is closely tied to Canada’s. In the 17th century, Louisiana was colonized by French Canadians in the name of the King of France. In the years that followed, additional waves of settlers came from French Canada to Louisiana, notably the Acadians, after their deportation by British troops in 1755. Today, Louisiana maintains a special cultural relationship with Canada and Quebec in particular.

Colonial Louisiana

In 1682, after completing a voyage from New France to the Mississippi River delta, French explorer René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle took possession of the entire territory drained by the great rivers and its tributaries, in the name of the King of France. France hoped to compete with the colonial powers of Britain and Spain by using the river for military and commercial purposes and in occupying its drainage basin. This immense territory, which the French named Louisiana, stretched from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and from the Allegheny mountain range (which are part of the Appalachian mountains) to the Rockies. It was then occupied by numerous Indigenous nations; in the Mississippi delta alone, they included the Bayougoula, Mugulasha, Chitimacha, Houma, Tangipahoa, Quinapi, Tunica, Opelousa, Biloxi, Pascagoula, Choctaw, Chapitoula, Atakapa, Acolapissa, Washa and Chawasha.

Starting in 1699, the French established colonies mainly along the Illinois River in the north and the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico in the south. The French-speaking settlers came first from France and its colonies (New France and the French Caribbean) and later from other European countries. Slavery became established practice. The first enslaved people were members of Indigenous nations, who often served as guides on voyages of exploration. Starting in 1719, traders began bringing enslaved Africans to Louisiana.

During the French colonial period in Louisiana, nepotism and corruption were widespread among both the Canadians and the French. King Louis XIV refused to make Louisiana an administrative part of New France, but nevertheless, it was mostly Canadian officers of the French army and navy who exercised authority in Louisiana in the name of the King. In 1718, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, a Canadian who was then commandant general for the French crown in Louisiana, founded the city of New Orleans.

Despite its immense size and its location, Louisiana was never a profitable colony for France and was therefore largely neglected. Very few French colonists came willingly. Most were forced to settle in Louisiana, largely because they were criminals or poor. In contrast, many French Canadian colonists came to Louisiana voluntarily. The colony’s successive governors preferred them, because they were used to harsh physical conditions and to relations with Indigenous people. During the first decades of French colonization, Canadians formed a majority of the settlers in areas such as Bayou Saint-Jean, Bayou Gentilly, and the banks of the Mississippi, but their relative importance diminished as new colonists arrived from elsewhere. Meanwhile, the Indigenous people fell victim to epidemics, attempts at assimilation by marriage or conversion to Christianity, as well as by armed violence. In 1729, the Natchez people rebelled against the intrusion of colonists onto their farmlands. The Natchez rebellion was suppressed by French governor Étienne Périer, who massacred some of the rebels, dispersed others, and sold others into slavery in Saint-Domingue.

Politically speaking, the French period in Louisiana lasted less than a century. France lost its Canadian territories to Great Britain in the Seven Year’s War. The French withdrawal from North America continued in 1762, when Louis XV abandoned New Orleans and the lands west of the Mississippi to his ally and relative, Charles III, King of Spain. Charles waited until 1766 to send troops to this part of Louisiana, and established his authority there in 1769. French-speaking settlers resisted Spanish authority. France ceded the territory east of the Mississippi to Great Britain by the Treaty of Paris (1763).

In 1766, when Spain occupied the Louisiana colony, it had scarcely 7,500 inhabitants. Most of them were French-speakers, including “free people of colour”, meaning freed slaves as well as those descended from relations between enslaved Africans and colonists.

The Acadian Deportation and Louisiana

French-speakers still constituted a large proportion of the immigrants to Louisiana during the Spanish period. At least 780 Acadians deported to the British colonies of Maryland and Pennsylvania later migrated to Louisiana between 1766 and 1770. In 1785, they were joined by nearly 1,600 more Acadians who, after being deported to England, had managed to reach the French mainland (see also Deportation from Canada). The episode of their deportation from Acadia, most of which was in present-day Nova Scotia and where they formed a fairly homogeneous and isolated community, is known as the Great Upheaval. The scattering of the Acadians is the subject of the poem Evangeline (1847), by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose heroine has become the symbol of the history of the Acadians, despite the historical errors that the poem contains.

Americanization of Louisiana and Louisiana Francophones

Louisiana was returned to France by the treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800. But Napoleon Bonapart knew that he could not defend such a large territory against the English, so he sold Louisiana to the United States for $15 million in 1803. At that time, Louisiana had a population of 50,000. In 1809, during the war between France and Spain, nearly 10,000 francophones who had taken refuge in Cuba after the Haitian Revolution in Saint-Domingue (1791 - 1804) left Cuba for Louisiana. New Orleans saw its population double with this massive influx of refugees, including both whites and free and enslaved Blacks.

In the mid-19th century, New Orleans became a major economic power thanks to its port from which the cotton and sugar produced by enslaved Blacks on Louisiana plantations were exported. Louisiana’s dynamic economy attracted immigrants from Europe (including francophones from France, Belgium and Switzerland) as well as from the Caribbean, along with Americans and enslaved Africans from other states (over 20,000 in the 1830s alone).

The process of Americanization then ensued and led to the gradual assimilation of the groups of French-speakers already present in Louisiana: white Creoles (descendants of the French and Spanish colonists), Creoles of colour (descendants of the “free people of colour”), enslaved Blacks and Acadians. By the 1830s, French-speakers had become a minority and lost political control, first in New Orleans, and then in the rest of the Louisiana. But some cultural institutions remained. The Théâtre de l’Opéra français (French Opera House) continued to present works in French. Authors such as Victor Séjour continued to write literature in French. French-language newspapers continued to be published, including L’Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans, La Sentinelle de Thibodaux, Le Meschacébé and Le Messager and some published by Creoles of colour, such as La Tribune de la Nouvelle-Orléans. But starting in the 1860s, French was no longer taught except in certain Catholic private schools. In public primary schools, the teaching of French was even prohibited. Americanization had led to the near disappearance of French life in Louisiana, and the process of assimilation accelerated after the Second World War. The use of French at school was prohibited and subject to punishment.

Today, fewer than 100,000 Louisianans age 5 and older (about 2% of the population) speak Louisiana or Cajun French. The diverse origins of these French-speakers include an Indigenous people, the Houma, who live in the flood plains along Louisiana’s Gulf coast. Cajuns constitute the greatest concentration of French-speakers in 22 parishes in the southern part of the state, an area that the Louisiana legislature has designated “Acadiana” (in English) and “Acadiane” (in French) since 1971.

French Culture in Louisiana

Despite this decline, French is still spoken in some Creole and Cajun communities of Louisiana that have an important oral tradition. The 1970s saw a renewal of Cajun culture and a rehabilitation of Cajun identity: Revon Reed published Lâche pas la patate, a portrait of the Acadians of Louisiana (1976).

In 1980, Jean Arseneaux published Cris sur le bayou, the first anthology of Cajun poetry, featuring many male and female poets.

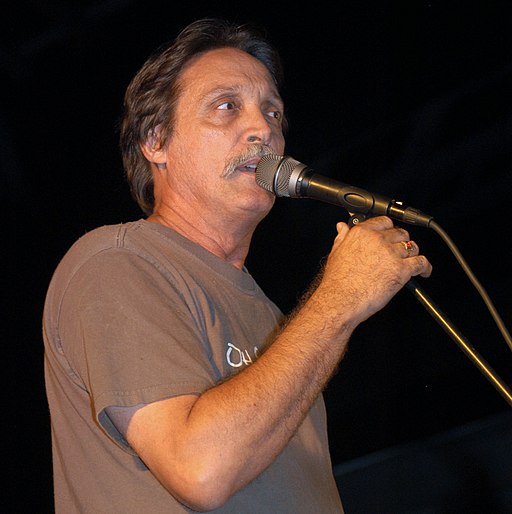

In the 1990s, Cajun artists in various disciplines achieved international success, including Debbie Clifton, David Cheramie and Jean Arseneaux with collections of their French-language poetry published by Les Éditions Perce-Neige, of Moncton, New Brunswick, and singer-songwriter Zachary Richard with Cap Enragé (1996), his international hit album of songs entirely in French. Cajun music stepped into the spotlight when artists such as the Lost Bayou Ramblers and accordionist Bruce Daigrepont began performing at festivals such as the Louisiana Cajun-Zydeco Festival in New Orleans and the Festival international de Louisiane in Lafayette.

In 1996, Zachary Richard and other champions of Cajun culture founded the association Action Cadienne to defend, in the words of its manifesto, “the French language as it has been handed down to us from generation to generation… the profound source of our identity.” A dictionary of Louisiana French was published in 2009. But as scholar André Thibault has noted, Louisiana French is in no sense the direct descendant of the French spoken by the Acadian deportees, because it has also been influenced by the various other groups of French-speakers who have come to Louisiana since its colonization began. In 1994, the University of Southwestern Louisiana (now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette) established the first doctoral program in Francophone Studies in the United States. In 1998, Louisiana State University in Bâton Rouge created a Cajun French studies program. In 1999, the University of Louisiana at Lafayette offered its first course in Louisiana Creole.

Relations between Louisiana and the Canadian Francophonie

The Quiet Revolution in Quebec revived bilateral relations between Canada and Louisiana, which had lain dormant for nearly two centuries. Quebec, though it had no official ties with the U.S. government, developed quasi-diplomatic relations with many communities, notably those in Louisiana, and in particular its francophones. This new era of collaboration was inaugurated by Quebec premier Jean Lesage when he visited Louisiana in 1963. Quebec and Louisiana signed a cultural cooperation agreement in 1969, and the Bureau du Québec opened an office in Lafayette in 1969 (see Relations internationales du Québec).

In 1968, with support from Quebec and a number of French-speaking countries, the Louisiana state government established the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL), which works to restore pride in Cajun identity. In 1968, Louisiana passed a set of laws designed to preserve the French language and revive the teaching of French in the state. Quebec, France and Belgium all sent teachers to Louisiana in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s (starting in 1981, for immersion programs), particularly in the Cajun communities of southwestern Louisiana (Ivory Coast and Haiti contributed as well).

In the 1980s, relations between Quebec and Louisiana declined. In 1990, Quebec downgraded its Government Office in Lafayette to a “representation”, with a mainly economic focus, and closed it in April 1992. Bilateral relations continued in the areas of culture, tourism and business, but with less intensity. In 2015, the legislatures of Quebec and Louisiana signed a cooperation agreement. Since the 1990s, Louisiana has established cultural ties with the Maritime Provinces (Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick), with the promotion of Acadian and Cajun identity as their common focus. Since 1994, the Acadian World Congress has been held every five years, alternating between Canada and the United States. Louisiana continues to arouse curiosity and interest in Canada, as witness the Canadian films about Louisiana that have been produced in recent years (Marron, la piste créole en Amérique, by André Gladu, in 2005 and Zachary Richard, toujours batailleur, by Phil Comeau, in 2016).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom