From April to December 2009, Canada experienced an outbreak of influenza A (H1N1). The virus began in North America and spread to many other countries in a global pandemic. This new type of flu differed from the typical seasonal flu, and its effects were more severe. Worldwide, more than 18,000 people are confirmed to have died of H1N1, including 428 Canadians. Estimates based on statistical models have put global deaths much higher. Totals may have been in the hundreds of thousands. The H1N1 pandemic tested Canada’s improvements to its public health system after the SARS outbreak of 2003. On the whole, it revealed a more efficient, coordinated response.

Click here for definitions of key terms used in this article.

Image of the H1N1 influenza virus, taken in the CDC Influenza Laboratory.

Origins of Influenza A (H1N1)

The H1N1 flu virus was first reported in Mexico in March 2009. Initially referred to as the “swine flu,” the virus had never been seen before in either animals or humans. However, it was thought to be most closely related to influenza viruses found in pigs in North America and Eurasia. Later, scientists discovered that it did not only contain elements of North American and Eurasian swine flu. The virus also contained aspects of North American bird and human influenza. Antibodies people had developed in response to the seasonal flu did not protect them against H1N1.

Pre-Pandemic Period

On 26 April 2009, the Public Health Agency of Canada reported the country’s first cases of H1N1. Canadian laboratories carried out early testing of virus specimens from Mexico. By early May, Canadian scientists had completed the first full genetic sequencing of the H1N1 virus. This step was key to developing a vaccine.

The Pandemic in Canada

By 11 June 2009, 74 countries had laboratory-confirmed cases of H1N1. The World Health Organization announced a pandemic. It had been four decades since the previous flu pandemic in 1968.

Unlike the seasonal flu common during the winter, H1N1 struck many Canadians between the spring and fall. There were two waves of infections in Canada, peaking in mid-June and early November 2009. While 8,678 people were hospitalized with confirmed cases of H1N1, probable cases brought the total to about 15,000. Most cases needing hospital care occurred during the second wave. Young children, pregnant women, new mothers, people with underlying health conditions and the severely obese were most at risk.

The H1N1 virus impacted the population differently than typical seasonal influenza in several ways. For one, the infection rate was lower among the elderly. Hospitalization rates also revealed differences. The hospitalization rate for children under five far surpassed that of other age groups. This disparity was much greater than in a baseline flu year. Also, of the total number of people hospitalized, many more were between 20 and 64 years old. During the H1N1 pandemic, 47 per cent of patients were in this age group, compared to 26 per cent in a baseline flu year. Finally, patients with H1N1 were more likely to need ventilation and treatment on intensive care units (ICUs). During the pandemic, 1,473 H1N1 patients were admitted to ICUs.

Indigenous people were disproportionately affected by the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. While they made up around 4 per cent of the population, they represented at least 16 per cent of those hospitalized during the first wave of the pandemic and 6.1 per cent during the second. Remote and isolated communities suffered the worst impacts. Researchers have proposed various possible reasons for the disparity. Lack of access to health services, overcrowding, a younger population and lower socio-economic status may all have contributed to the severity of H1N1 in these communities. (See also Health of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Public Health Response

In Canada, all levels of government cooperated in their response to the H1N1 pandemic. At the federal level, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) led and regulated the nation’s efforts. Its influenza preparedness plan guided the response. This plan focused on surveillance, antiviral drugs, vaccines, public health measures, clinical care, research and communications.

Did you know?

The federal government formed the PHAC in 2004. In part, the agency was a response to Canada’s failings during the 2003 SARS outbreak.

The provinces and territories are responsible for delivering health services. During the pandemic, they oversaw front-line measures such as vaccination and patient care. During the second wave, some hospitals increased their capacity and limited certain types of ICU admissions to make room for H1N1 patients. Many hospitals bought more ventilators and trained more staff on their use.

Governments also funded public education to prevent the spread of the disease. Campaigns emphasized the importance of hand washing, coughing in one’s sleeve and staying home when sick.

Vaccination

In mid-October 2009, Health Canada approved a vaccine for H1N1. Then began the largest vaccination campaign in Canadian history. Between 40 and 45 per cent of the population (13.5 to 15 million people) received the vaccine. Vaccination may not have limited the second wave of infections. This is because it came just before the second wave. The vaccine took 10-14 days after injection to create immunity. Vaccination may nevertheless have prevented a third wave of H1N1 in Canada.

A busy H1N1 vaccination clinic in Sudbury, Ontario on 27 October 2009.

(“H1N1 flu shot clinic - Tuesday 9:42 am 10/27/09 Greater Sudbury,” by Doug eastick at flickr is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.)

Doctors also widely prescribed antiviral medication during the second wave. These drugs helped treat the flu in its early stage and limited its severity.

By January 2010, the PHAC had begun to scale back its response to the pandemic. The World Health Organization declared the end of the H1N1 pandemic on 10 August 2010.

Significance and Legacy

There were 428 deaths in Canada from H1N1. The country spent more than $2 billion on its response.

Health journalist André Picard applauded Canada’s response in a May 2010 column for the Globe and Mail. “Public health officials acquitted themselves pretty well given the scientific and political challenges posed by H1N1,” he wrote. “And when you compare the response to H1N1 to that of SARS, it was night and day.” Picard argued that Canada had learned from the SARS crisis. He cited the pandemic preparedness plan and praised its efficient implementation across the country. Picard did, however, point to failures in messaging from health officials. He observed that some of their communications about vaccination had created confusion. The Senate and PHAC would both issue reports on the pandemic response that echoed Picard’s view on this point.

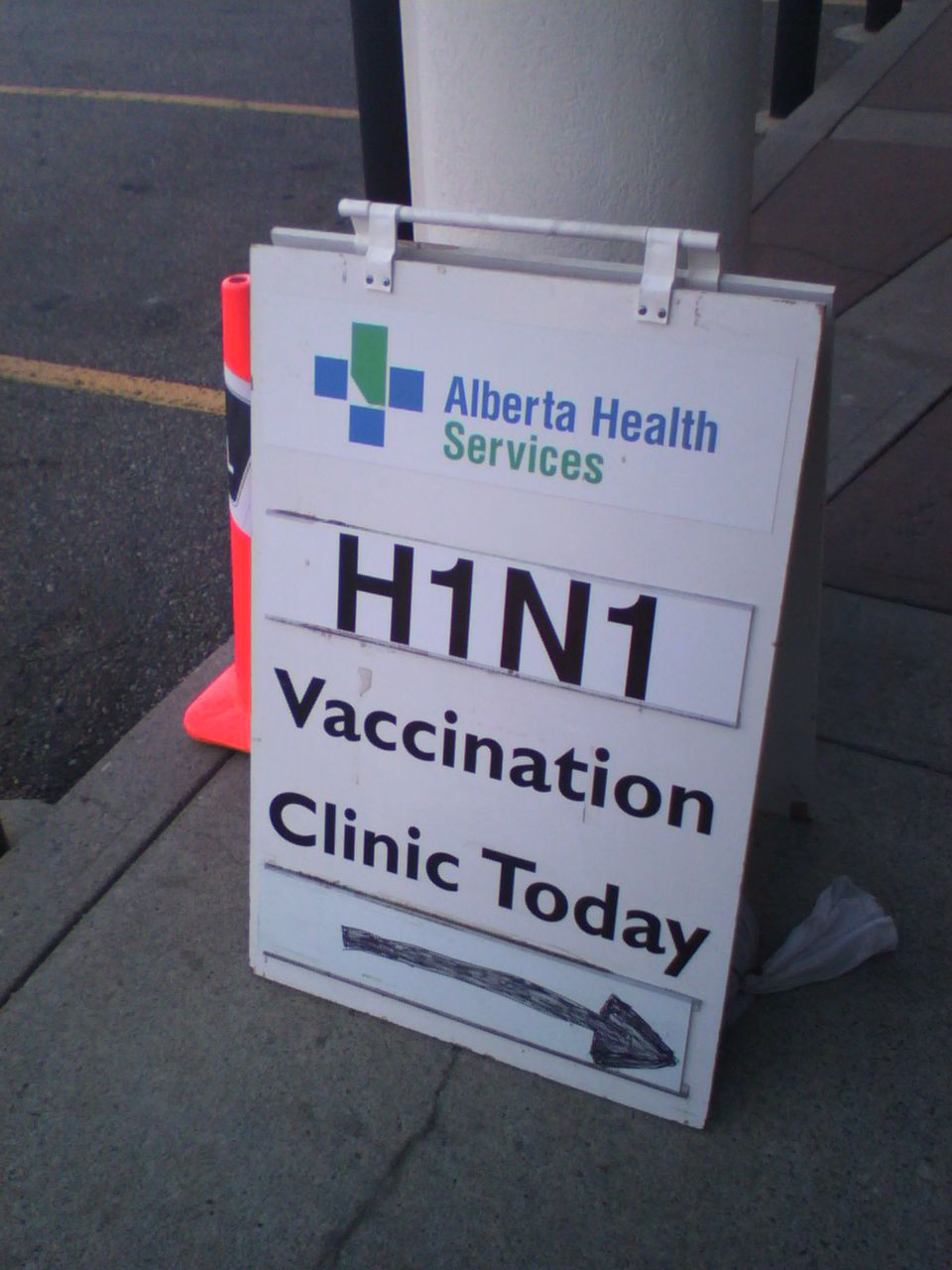

Sign outside a Calgary clinic offering the H1N1 vaccine.

(“Calgary H1N1 Vaccination - pix 1” by Kempton at flickr is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.)

Later in 2010, Ken Scott, director of the PHAC’s Pandemic Preparedness Division, reported on Canada’s response. He guessed that if the country had not applied the pandemic plan, thousands of healthy young Canadians would have died. However, he also identified “unfinished business” in areas where the plan could be improved. These included clearer roles, more effective information sharing, overall surveillance, timelier guidance for health workers and timelier vaccination.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom