Founding and Growth

When first founded in 1936, the organization was known as Jeunesses Saint-Eusèbe, after the name of the Montréal parish where it had its roots. Pursuing its goal of uniting young French-Canadian nationalists, the movement grew rapidly, establishing chapters in other parishes in Québec and even in Ontario. In 1940, it adopted the name Jeunesses Laurentiennes, in honour of the St. Lawrence River. Three years later, it opened its doors to young women and established women’s chapters. At the height of its success, Jeunesses Laurentiennes had nearly 5,000 members in some 200 chapters. The organization remained active until it ceased operation in 1950.

Ideology and Activities

Jeunesses Laurentiennes subscribed to a traditionalist French-Canadian nationalism, with a doctrine of two founding peoples and the need for a decentralized federal authority. Thus the organization saw Canada as being composed of two peoples living in a single State. Jeunesses Laurentiennes defended French-Canadians’ identification with Catholicism and criticized the rise of materialism and individualism, which they perceived as the Americanization of French-Canadian society. They also denounced the inferior economic status of French Canadians and their near absence as managers in large companies and heads of financial institutions. Jeunesses Laurentiennes did not support any political party, and its by-laws prohibited its members holding important positions to get involved in politics. But the organization did support the ideas of the nationalist priest Lionel Groulx, whose writings were among the youth movement’s recommended readings and were studied at its meetings. Father Groulx attended most Jeunesses Laurentiennes general meetings and even became the organization’s chaplain in 1947.

Not content simply to state their ideas, the Jeunes Laurentiens actively defended and disseminated them. To do so, they developed a program, gave lectures, founded credit unions and organized celebrations, notably for the Fête de Dollard (see Dollard des Ormeaux) and Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day. Jeunesses Laurentiennes also published a magazine and even occasionally acted as a pressure group, opposing Sunday labour and the acceptance of non-Catholic, non-francophone immigrants. The organization also lobbied the government of Canada to open an embassy in the Vatican and the government of Québec to adopt a fleur de lys design as Québec’s national flag.

During the Second World War, Jeunesses Laurentiennes opposed conscription. In 1942, after having promised not to resort to conscription, Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King held a plebiscite to try to get out of his promise. At this time, Jeunesses Laurentiennes supported the efforts of the Ligue pour la défense du Canada to urge French-Canadians to vote against conscription in the plebiscite. Members of Jeunesses Laurentiennes made speeches on the subject on the radio and at rallies, held public meetings and participated in public meetings of the Ligueas well. Similarly, many members of Jeunesses Laurentiennes also became involved in the Bloc populaire canadien.

Role in the Francophone Nationalist Movement

As part of the broader francophone nationalist movement of its time, Jeunesses Laurentiennes maintained ties with many other organizations that endorsed similar beliefs. On many occasions it cooperated with Catholic lay organizations and clergy to rally French-Canadian youth in support of a traditionalist ideology. Some members of Jeunesses Laurentiennesattended the study days organized by these Catholic lay organizations, while members of these organizations participated in activities organized by Jeunesses Laurentiennes.

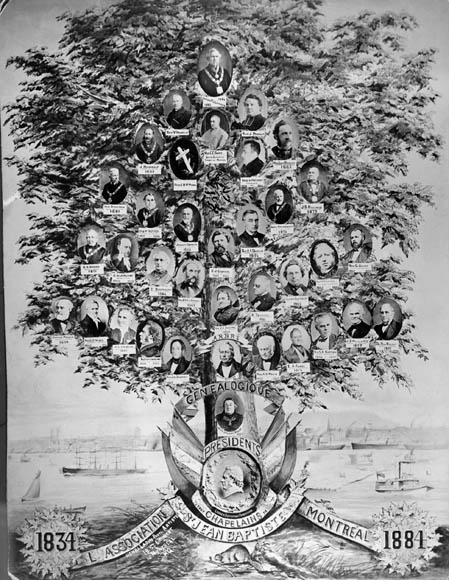

Jeunesses Laurentiennes also maintained excellent relations with nationalist groups composed of older activists. In particular it received both financial and moral support from various branches of the Sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste (SSJB) as well as assistance from the Ordre de Jacques-Cartier (OJC). In order to support Jeunesses Laurentiennes officially, the OJC asked its members to come to the organization’s assistance. But after having provided Jeunesses Laurentiennes with financial support, the OJC backed off, because of the financial difficulties that the youth organization was experiencing, difficulties that eventually became one of the reasons for its disbanding.

Impact of the Jeunesses Laurentiennes Movement

Although some of the ideas advocated by Jeunesses Laurentiennes were gradually set aside with the end of the Second World War, and even more so with the Quiet Revolution, this organization’s lasting impact on francophone nationalist movements in Canada was appreciable nonetheless. Many individuals who would one day play important roles in the development of French-Canadian nationalism, and subsequently of Québec nationalism, got their start as activists in the Jeunesses Laurentiennes movement.

One good example is Rosaire Morin, who became general secretary of Jeunesses Laurentiennes in 1943 and served as its president from 1945 to 1950. Subsequently, he became involved in the Ordre de Jacques-Cartier and later the Ordre de Jean-Talon and was one of the main organizers of the Estates General of French Canada. He also served as president of the Conseil d’expansion économique (council for economic expansion) and editor in chief of L’Action nationale. While a member of Jeunesses Laurentiennes, Morin argued for French-Canadian nationalism, but in the 1960s, he became an advocate of Québec nationalism instead. He was not unique in this respect; many other former Jeunesses Laurentiennes activists followed this same pattern. Examples include Paul-Émile Robert, who became president of the Société Saint-Jean Baptiste of Montréal when it endorsed Québec independence in 1964, and Gérard Turcotte, who became active in the Fédération des Sociétés Saint-Jean Baptiste, the Mouvement Québec français and the Parti Québécois.

In short, the impact of Jeunesses Laurentiennes continued to be felt long after the organization had ceased to exist. For its members, it was a veritable training academy in nationalist activism. Many of them remained active in the nationalist movement. As Québec society changed, their ideas evolved along with it, so that they eventually became Québec nationalists.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom