Consider Mohawk chief John Norton’s role in the pivotal Battle of Queenston Heights during the War of 1812. Without the efforts of Norton and about 80 Grand River warriors in repelling more than 1,000 American soldiers, the battle might have been lost, and the tide of war turned.

Norton was, by any measure, unique. Born in Scotland around 1760 to a Scottish mother and Cherokee father taken from North America by British soldiers, Norton enlisted with the British army in 1784, was posted to North America in 1785, and deserted the army two years later while serving in Niagara (he was later pardoned and received an official discharge). He became involved with the Six Nations of Grand River, and learned the Mohawk language and culture under its chief, Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), who adopted Norton as his nephew. That gave Norton the status of chief, and the name Teyoninhokarawen, which in Mohawk means “open door.” Despite his desertion, he kept close contact with the British, remained a devout Anglican, and was considered an ally by the administration.

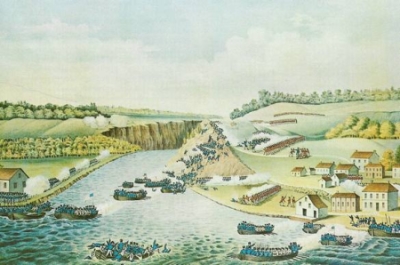

With the outbreak of war, Norton (then in his early 50s) was made a captain by the British, and began recruiting Grand River Mohawk and others to fight. They had a reputation as fierce warriors and soon had a chance to prove it. On 13 October 1812, more than 1,000 American troops crossed the Niagara, seeking to take control of Queenston Heights. Part of the American force reached the top, circled the British artillery position and forced the Redcoats from the Heights. General Isaac Brock, one of the most respected British military leaders of his day, was killed leading a counter-attack (see Isaac Brock: Fallen Hero).

With British troops in potential disarray, Norton, John Brant, and about 80 other Six Nations and Delaware warriors stepped in — and stepped up. Outnumbered more than 10 to 1, they held back the Americans for hours — long enough for reinforcements to arrive so that the British could retain the crucial outpost.

That effort by Norton and the Six Nations warriors was a remarkable contribution to the war effort, but it was far from their only one. In the following year, Norton and his warriors covered the British retreat to Burlington Heights after the Americans took Fort Niagara, provided scouts before a successful night attack at the Battle of Stoney Creek and contributed to the rout of the Americans at the Battle of Beaver Dams.

After the war, Norton was given the brevet rank of major. Overall, Indigenous people made up as much as 10 per cent of British forces in the war. In 2012, Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced the creation of the Canadian Forces War of 1812 Commemorative Banner and Medals to be given to successor First Nations and Métis communities. As the Prime Minister said, “Canada’s Aboriginal People were, in every sense, key to the victory that firmly established Canada as a distinct country in North America.” And so we also pay tribute to efforts that shaped not only our past, but also the nation that we are today.

(See also First Nations and Métis Peoples in the War of 1812.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom