The Kinmel Park Riot (4–5 March 1919) was one of several demobilization riots at the end of the First World War. Five Canadian soldiers died during the riot, which happened at the Canadian Army camp at Kinmel Park near Rhyl in North Wales. It was the most serious of 13 riots or disturbances involving Canadian troops in the United Kingdom between November 1918 and June 1919.

Demobilization and Repatriation

After the Armistice of 11 November 1918 ended the fighting of the First World War, more than 250,000 Canadian troops awaited repatriation to Canada. Although some soldiers had been sent home by the end of the year, the majority were still in Europe in January 1919. By that time, the Canadian government had finalized plans for repatriation. Upon the recommendation of Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force in France were given two weeks’ leave in England to visit family and friends, after which they would reassemble for transport home. The rest would be housed in one of nine different camps in Britain, before travelling to Kinmel Park Camp in Wales, about 48 km from Liverpool. They would spend 7–10 days at Kinmel before boarding a ship at Liverpool for the journey home.

The Canadians experienced significant delays, however, due to competition for shipping among the Allied powers. Labour disruption also played a role. British dockworkers, seamen, miners and police struck for higher pay, contributing to further delay and to shortages of food and coal during an unusually cold winter in Britain. Conditions were miserable. Soldiers and civilians were also affected by the “Spanish flu” pandemic, which killed between 20 and 100 million people worldwide in 1918–19. Riots and disturbances broke out among frustrated and homesick Canadian troops — as they did among British soldiers.

Did you know?

John Babcock, who died on 18 February 2010 at age 109, was Canada’s last surviving soldier of the First World War. He enrolled when he was 15 and eventually made it to England. When his age was discovered, he was transferred to Kinmel Park Camp along with other underage soldiers. Although Babcock was not involved in the March 1919 riot, he and his friends did cause some trouble while at Kinmel. Shortly after the armistice was signed in November 1918, they were prevented from entering a dance by a bunch of British officer cadets. Babcock and his friends charged the hall, armed with an assortment of bricks and sticks. After a bit of property damage and a few non-lethal injuries, their officers convinced them to return to quarters.

Conditions at Kinmel Park

At Kinmel Park in Wales, thousands of Canadian soldiers waited to return home. The camp, which at one point housed more than 17,000 soldiers, covered a large area and was subdivided into 20 cantonments. These were organized in eleven wings, one for each of the military districts in Canada. Each wing had its own barracks, mess halls and training facilities. The camp also had a large military hospital. The soldiers were grouped according to the military districts in Canada from which they had come, rather than in the regimental units in which they had served and formed bonds of friendship. They did not know their officers in the camp, resulting in feelings of alienation.

Although the men received an adequate diet, it was monotonous. In theory, soldiers could supplement their diet by purchasing goods at the local “Tin Town,” a shanty-like collection of shops, canteens and pubs on the outskirts of camp. Unfortunately, many soldiers didn’t have money to spend in Tin Town; they were only entitled to one pay before repatriation, and most of them had spent it during their extended stay. They also believed that shop operators were dishonest and charged inflated prices to Canadian soldiers.

Soldiers were forced to perform exercises and route marches daily, which they considered pointless. It was a cold, wet winter and after a period of continuous rain in February, the camp was a sea of mud. To add to the men’s misery, the “Spanish flu” pandemic of 1918–19 swept through the camp, causing about 80 deaths. The soldiers complained, but little was done. Canadian Minister of Overseas Military Forces, Sir Edward Kemp commented, “You cannot blame the soldiers for kicking and complaining … You are living in paradise in Canada as compared to this place.”

Voyage Home Postponed

The soldiers at Kinmel believed they would return to Canada on the basis of “first over, first back.” They were anxious to return, not only to see loved ones but also to increase their chances of finding employment. But their hopes were soon frustrated. At the end of February, news reached Kinmel Park that ships allocated for Canadians had been reassigned to the Americans, who had not been in Europe as long. Then, about the beginning of March, the men learned that General Currie had decided to give the Canadian 3rd Division priority (the 1st and 2nd Divisions were part of the occupation force in Germany). This angered some of the troops in Kinmel who had been overseas longer.

Finally, the SS Haveford, which was supposed to take soldiers from Kinmel on 5 March, was rejected by inspectors because of substandard conditions. After the camp commander complained, additional ships were promised for the men at Kinmel. The soldiers, however, were not aware of this — only that the Harveford sailing had been cancelled. By that point, some of the soldiers had been at Kinmel Camp for six weeks — much longer than originally promised.

Kinmel Park Riot

On the evening of 4 March, crowds of angry soldiers raided and looted canteens, quartermaster’s stores and officers’ and sergeants’ messes. Uniquely, The Salvation Army canteen was not attacked, as soldiers knew it was the one place where they could get a coffee and a snack even when penniless. The disturbances spread to Tin Town, where fires broke out and looters carried off thousands of dollars worth of beer and liquor, cigarettes, clothing and equipment. A few staff officers tried to intervene, but to little effect as they were largely inexperienced.

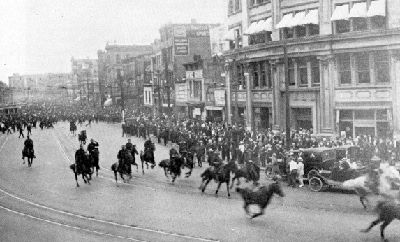

On the morning of 5 March, Camp Commandant Colonel Malcolm A. Colquhoun ordered all ammunition to be collected and placed under guard. He also directed each man be paid £2. Since there were no military police in the camp, he ordered the Canadian Reserve Cavalry Regiment to establish a mobile reserve of 25 mounted troopers. A defensive perimeter was established, and ammunition was issued to 40 officers and soldiers considered trustworthy. The rioters had only a few firearms, but many had armed themselves with makeshift weapons — stones, broom handles and sticks with straight razors attached.

The camp defenders clashed with the rioters and seized 20 men. An attempt to liberate the prisoners was thwarted. The violence continued — shots were fired, and the two sides engaged in hand-to-hand fighting that included the use of bayonets. The rioters finally surrendered after three of their number were killed or mortally wounded. Two guards also died during the riot. Twenty-three men were wounded.

Aftermath and Significance

In total, 78 soldiers were arrested, of whom 59 faced court martial under the British Army Act. Twenty-five were convicted and sentenced to terms ranging from 90 days in detention to ten years in prison for one soldier. Some of the more severe penalties were later reduced. No one was charged for the deaths, as inquiries were inconclusive. Most of the men in Kinmel Park Camp were sent home by the end of March 1919.

Historians have suggested a combination of reasons for the Kinmel Park Riot, echoing the military investigation at the time. Delays and cancellations were key reasons, but poor communication also played an important role. So too, did the lack of unit cohesion and identification. Soldiers had been separated from their regimental officers and compatriots; they didn’t know or respect the camp’s officers, who as a group provided poor leadership and discipline. Other factors included boredom, poor accommodation and recreation facilities, monotonous food, lack of pay, and inclement weather.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom