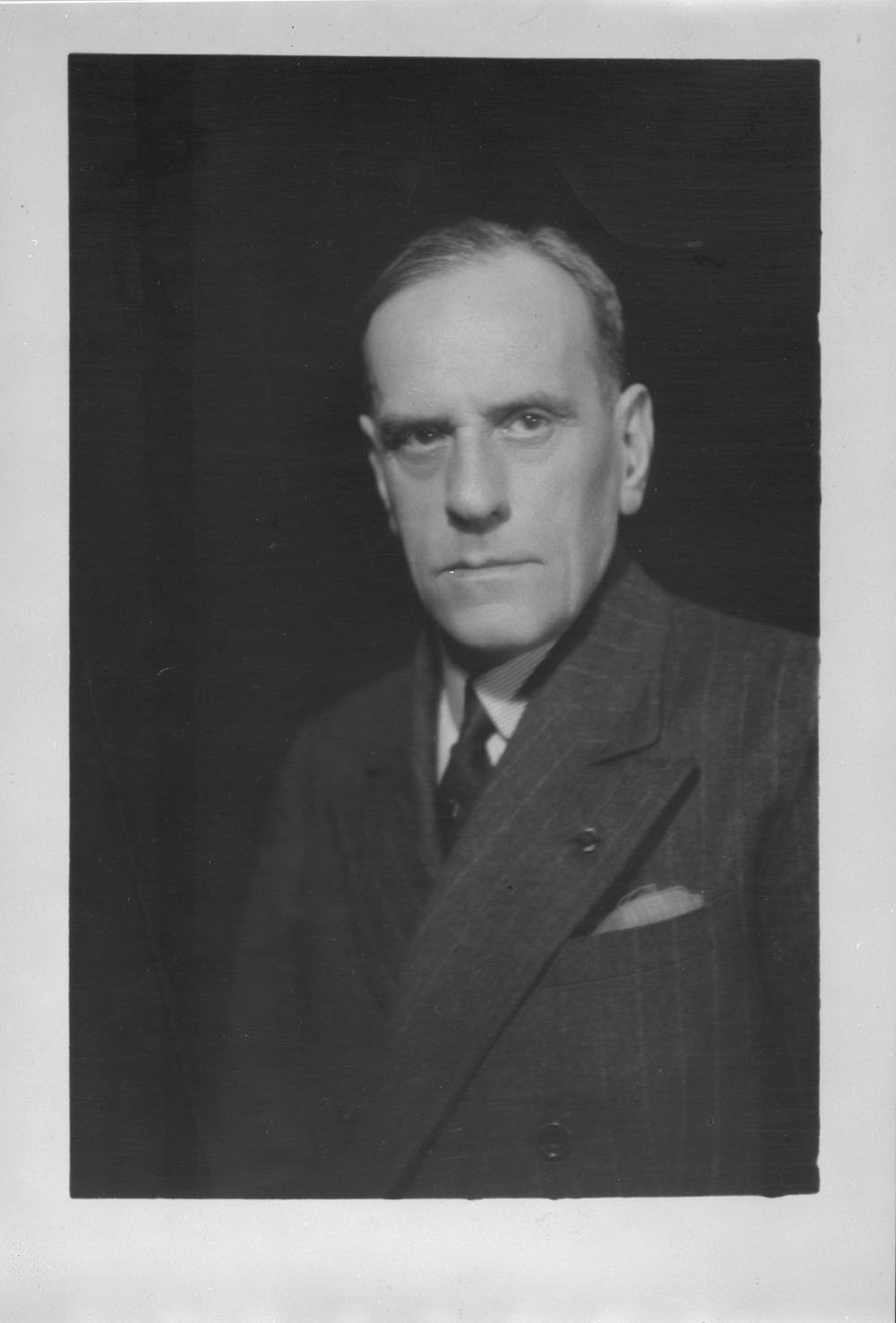

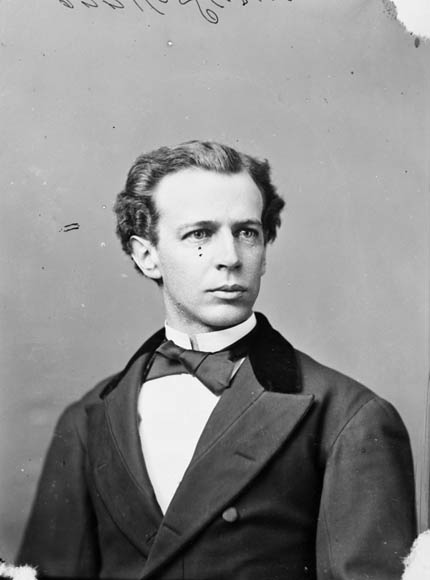

Family, Education and Early Career

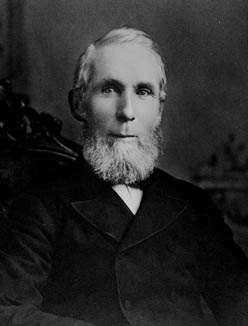

Laurent-Olivier David was the son of Stanislas David — a major in the militia and a farmer — and Élizabeth Tremblay. In 1869, he married Albina Chenet, who died in 1887. His second marriage, in 1892, was to Ludivine Garceau, who died in 1915. His first marriage produced a son (Athanase David, who later became a minister in the governments of Lomer Gouin and Louis-Alexandre Taschereau) and nine daughters. He was the grandfather of Senator Paul David and the great-grandfather of Liberal minister Hélène David, and of Françoise David, the former co-spokesperson for the political party Québec solidaire.

David attended collège classique (classical college) at the Petit Séminaire de Sainte-Thérèse. He then enrolled at the École de droit de François-Maximilien Bibaud (law school), established at the Collège Sainte-Marie de Montréal, and was admitted to the Lower Canada Bar in 1864. He practised as a lawyer until 1872, notably alongside Joseph-Alfred Mousseau, who was the premier of Québec from 1882 to 1884 under the banner of the Conservative Party of Québec.

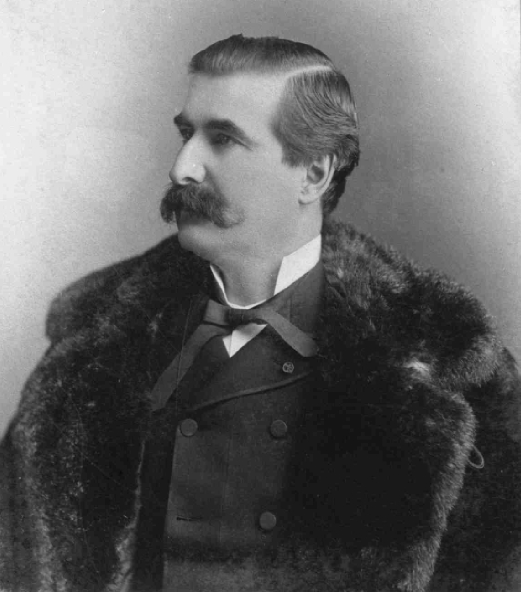

Journalism and Politics

From 1862 to 1884, journalism played an important role in David’s life. He was the co-owner of the newspaper Le Colonisateur (1862–63) and editor of the anti-federalist newspaper L’Union nationale (1864–67). He also started up two newspapers in collaboration with journalists and political figures of the day. In 1870, he founded L’Opinion publique, an illustrated weekly, with Joseph-Alfred Mousseau and printer George-Édouard Desbarats. David was the editor-in-chief of that newspaper until 1873. In 1874, he and Cléophas Beausoleil founded the newspaper Le Bien public, which became the official mouthpiece of the Parti national. David was co-owner and editor-in-chief until 1876. At that same time, he was a writer for and owner and editor of the daily Le Courrier de Montréal (1874–76). He then became owner of and writer for La Tribune (1880–84) and a contributor to the newspaper Le Temps.

Under the government of Alexander Mackenzie, David worked as translator and deputy clerk of elections and debates in the House of Commons (1876–78). He was the unsuccessful Liberal candidate in the riding of Hochelaga for the legislative assembly of the province of Québec in 1867 and 1875, as well as for the House of Commons in 1878. However, he won the riding of Montréal-Est in the provincial election of 1886 and entered the legislative assembly as a Liberal member. He did not stand for election in 1890 but instead ran in the federal election of 1891 in Montréal-Est, where he was defeated. He ran one last time, without success, in Napierville during the provincial election of 1892. From 1892 to 1918, David was clerk of the Montréal municipal council and, from June 1903, he performed this role as well as that of Senator for the Mille Isles Senate division, a position he occupied until his death in 1926. David was also offered the post of lieutenant-governor of the Northwest Territories, but he refused it.

Militancy

David was a member of various organizations, including the Club canadien, the Ligue antialcoolique (a temperance league) and the Société de protection des femmes et des enfants (society for the protection of women and children). He espoused temperance and believed that only wine and beer should be sold in Québec. As a member of the legislative assembly, he tried to have a law enacted to this effect, but he did not succeed because the committee charged with studying the bill never tabled its report. He also dedicated substantial energy to the working class debt (see Working Class History – Québec). At that time, workers could have all their furniture seized and up to three-quarters of their salary or wages forfeited for the payment of debts. As a result, David had several bills adopted to restrict such prohibitive practices by creditors.

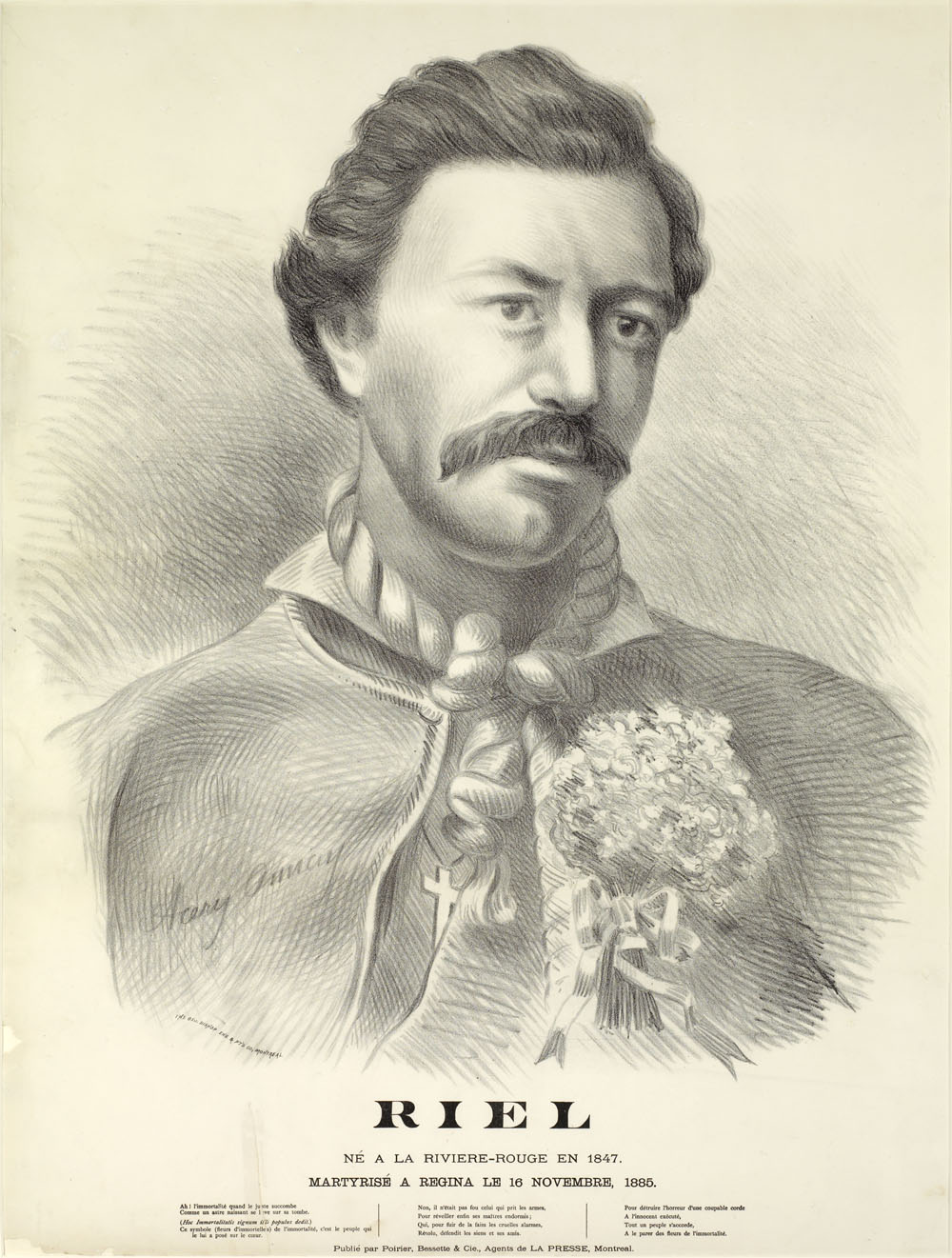

In terms of the economy, David favoured a protectionist approach. He campaigned in L’Opinion publique and at popular assemblies for the government to protect domestic industry and, in the end, his views prevailed. For four decades, David also defended colonization and, in particular, he fought to eradicate poverty among settlers. He believed that the government should provide grants to cover settlers’initial expenditures, such as those related to building houses and purchasing farm animals and implements. Following the Métis Red River Rebellion, David set up a committee of Louis Riel’s friends, which David co-chaired with Conservative George Duhamel. Organizing meetings and sending letters and petitions, the group made every effort to keep Louis Riel from being hanged.

Legacy

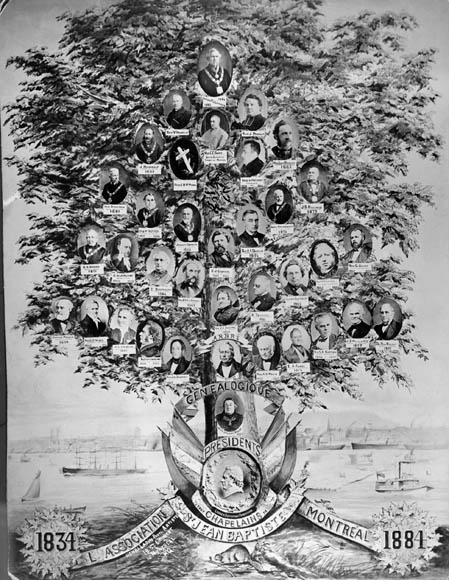

From 1887 to 1893, David was president of the Montréal Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. In 1888, he was a delegate to the Convention nationale des Canadiens-français des États-Unis, which took place in Nashua, New Hampshire. In 1874, 1880 and 1884, he was an active participant in organizing these major conventions that brought together representatives of French-Canadian, Acadian and Franco-American communities. In 1888, in order to give the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste practical ways to get involved in these social movements, David proposed an idea he had had in mind for years: building the Monument-National. Despite financial problems, the project finally came together in 1890, when David was the member of the legislative assembly for Montréal-Est and he had the support of the premier, Honoré Mercier. The Monument-National was completed in 1894 and served at different times as a school, an office, a theatre and a music hall. David had one of his plays — Le drapeau de Carillon (1902), a historical drama in three acts — performed there. His interest in promoting the French fact in North America was a constant in his life. In France, David organized erecting a monument dedicated to General Montcalm, and his rich and detailed writings on the Patriotes of 1837–38 presented them as national heroes and meritorious political figures who not only seized the opportunity to revolt but also understood the need to evolve, even toward political conservatism.

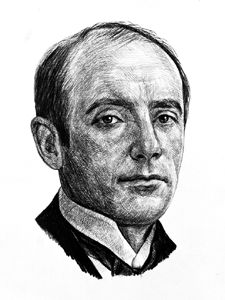

Conservative at the beginning of his public life, David was opposed to Canadian confederation, which he felt was detrimentalto Canada East. David became a moderate Liberal over time and developed a friendship with Wilfrid Laurier, whose policies David supported, particularly on the Manitoba schools question (see Le Soleil). Unofficial ideologist of Laurier’s Liberals, David did his best to unite, as harmoniously as possible, a genteel Catholicism and a progressive interest in public education and social doctrine. He believed that educational programs were no longer adapted to the needs of the country and that they favoured liberal professions and religious vocations too much. In his view, French Canadians needed to receive practical training that would give them, like the anglophone population, access to high-paying jobs in the world of business and industry. To this end, he encouraged learning the English language. In David’s work Le clergé canadien, sa mission, son œuvre (The Canadian Clergyman: His Mission and His Work) (1896), which caused him great tribulation, he denounced the Church’s viewpoint and particularly its interference in elections. He later became more subtle in promoting his ideas. Thus, to advocate for the social model he sought to advance, he resorted largely to biographical texts, publishing numerous biographies of historical Canadians, which were indeed nods to the elitist character he valued (see also Biography in French).

Throughout his life, David consistently wrote in newspapers on a wide array of subjects: politics, business, the economy, colonization, industrialization, Canada’s relationship with the United States, the constitutional status of the province of Québec within Canada, workers’ strikes and women’s suffrage. His body of writing was immense. Expressed in sober and elegant prose, his work reflected the socio-political views of the francophone elite of his time. In 1922, Athanase David created the Prix David (today one of the Prix du Québec) in honour of his father. This prize recognizes the work of writers and scientists in Québec. Rue L.-O.-David, in Montréal, was named in memory of Laurent-Olivier David.

Publications (Selected)

Biographies et portraits (1876)

Le héros de Châteauguay (1883)

Les patriotes de 1837-1838 (1884)

Mes contemporains (1894)

Les deux Papineau (1896)

Le clergé canadien, sa mission, son œuvre (1896)

L’union des deux Canadas, 1841-1867 (1898)

Le drapeau de Carillon (1902)

Laurier et son temps (1905)

Histoire du Canada depuis la Confédération (1909)

Souvenirs et biographies, 1870-1910 (1911)

Mélanges historiques et littéraires (1917)

Laurier, sa vie, ses œuvres (1919)

Gerbes canadiennes (1921)

Au soir de la vie (1924)

Honours and Awards

Member of the Royal Society of Canada (1890)

President of the French Section, Royal Society of Canada (1904 and 1905)

Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor), Republic of France (1911)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom