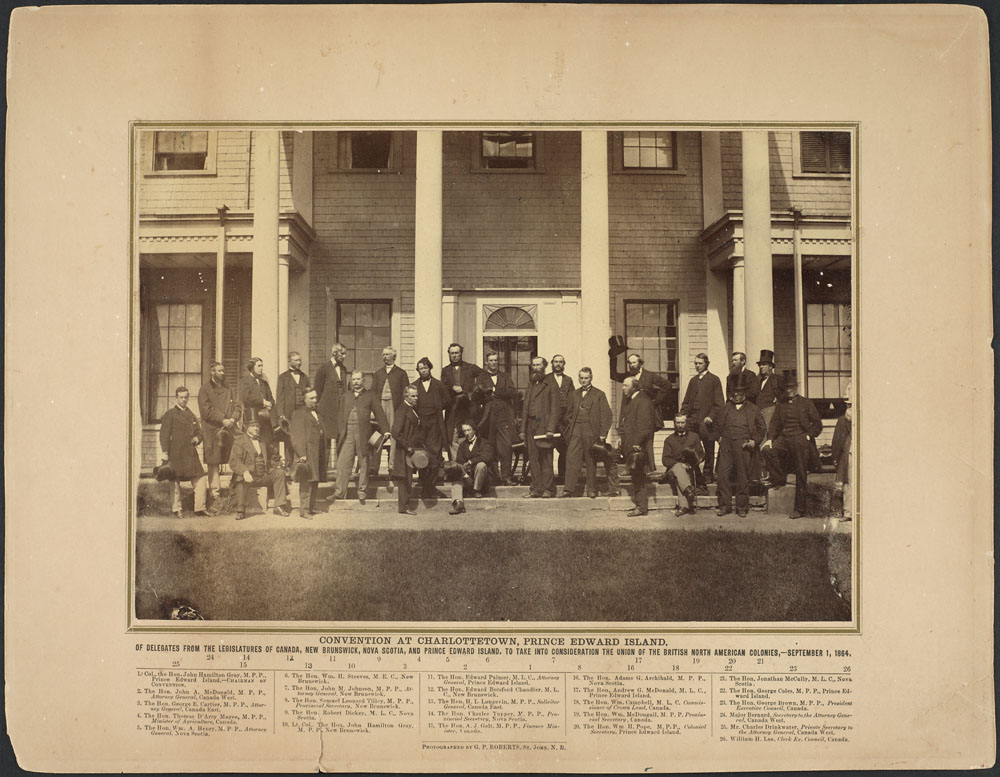

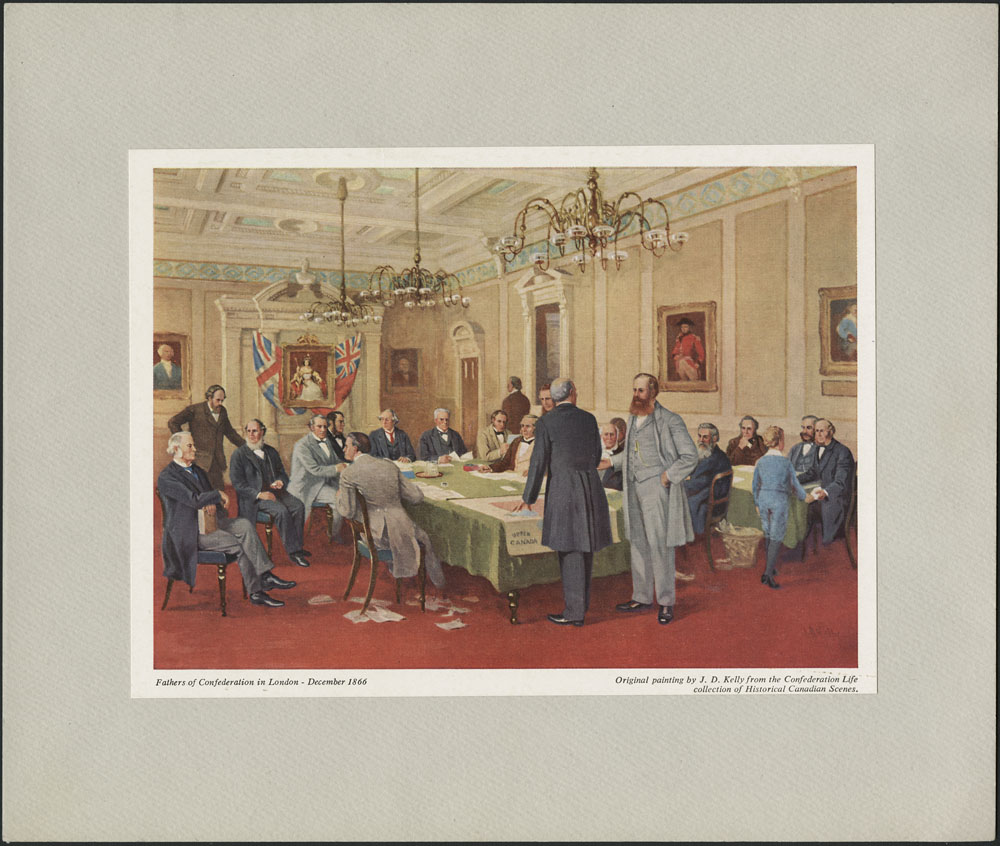

The London Conference took place in London, England, from 4 December 1866 to March 1867. Politicians from British North America met with members of the British government. This was the last of three conferences that were held to work out the legal details of Confederation. The first two were the Charlottetown Conference and Quebec Conference. They were both held in 1864. The Quebec Resolutions were agreed upon in Quebec City. They were reviewed and updated in London. They formed the basis of the British North America Act (now the Constitution Act, 1867). It is the foundation of Canada’s Constitution. It was passed by the British Parliament. It received Queen Victoria’s Royal Assent on 29 March 1867.

This article is a plain-language summary of the London Conference. If you would like to read about this topic in more depth, please see our full-length entry: London Conference.

Background

By the summer of 1866, the governments of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada had agreed to Confederation. (Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland took part in the Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences. But they did not join Confederation until later.)

The consent of the British Parliament was now needed. A draft for a British North America bill was finished in London in July. Delegates from the colonies had to go to England to agree to the details. The bill could then be sent to the British Parliament to be passed into law.

The bill was already on shaky ground. Prime Minister John Russell had approved of Confederation. But he was defeated in the House of Commons. He was replaced by Edward Smith Stanley (Lord Derby). He made Henry Herbert (Lord Carnarvon) the new colonial secretary. He took over the Confederation file. Carnarvon supported the British North America bill. But the new Derby government was weak. A crisis in Parliament could halt the bill’s progress and give its critics the chance to reject it.

Delays and Opponents

Plans were made for the BNA delegates to meet in London at the end of July 1866. The ones from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick arrived on time. But the Province of Canada’s team did not. It was led by John A. Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier.

Macdonald blamed Fenian troubles in Canada for the delay. (See also Fenian Raids.) In truth, he was worried about some technicalities. For one, the Province of Canada was set to be split into two provinces: Ontario and Quebec. But their constitutions had not yet been approved. Also, Charles Tupper warned Macdonald that an election would be held in Nova Scotia before May 1867. It would largely be fought on the issue of Confederation. And its outcome was uncertain. “We must obtain action during the present session of the Imperial Parliament, or all may be lost,” Tupper wrote.

The Maritime delegates couldn’t do anything in London without the Province of Canada delegates. And they couldn’t return home without achieving their goal. Meanwhile, an anti-Confederation group led by Nova Scotian Joseph Howe was also in London. (See Confederation’s Opponents.) They tried to turn British politicians against Confederation. Sir Charles Stanley Monck was governor general of the Province of Canada. He told Macdonald that “the Union scheme” must be brought before the British Parliament without delay.

Macdonald’s Leadership

The Province of Canada delegates finally went to London in November 1866. The conference was held at the Westminster Palace Hotel. The meetings began on 4 December. They were chaired by Macdonald. Sir Frederic Rogers of the British Colonial Office later called him “the ruling genius” of the group.

At Macdonald’s urging, everyone agreed to keep the meetings confidential. There would be no recorded minutes. This left Howe in the dark. He was not a delegate. Macdonald and Carnarvon also agreed to avoid publicity. They didn’t want there to be “premature discussion on imperfect information.”

Howe tried to discredit Macdonald as a drunkard. But Macdonald built a strong relationship with Carnarvon. Macdonald’s drinking habits did anger Carnarvon at times. But he still thought Macdonald was “the ablest politician in Upper Canada.”

Debate over Resolutions

Macdonald now urged the delegates to work fast. He knew that the election in Nova Scotia might lead to an anti-Confederation government. (See Nova Scotia and Confederation; “The Anti-Confederation Song.”) He also needed to act while the Derby government was still in power in Britain. Each change in the plan could lead to further demands and delays. So Macdonald wanted few changes to the Quebec Resolutions. They had been agreed upon at the Quebec Conference in 1864.

However, many delegates thought they should try and improve the 72 Resolutions. For example, Roman Catholic bishops in the Maritimes wanted separate schools for Roman Catholics to be guaranteed. Alexander Galt wanted to protect the rights of the English minority in Quebec. And Samuel L. Tilley and Charles Tupper wanted more federal funding for the Maritimes.

Delegates could not agree on just how binding the Resolutions should be. Some wanted to secure improvements before they would sign off on Confederation. Others disagreed. Macdonald allowed delegates to review all the Resolutions and make changes. By late December, they had the newly named London Resolutions. They submitted these to the Colonial Office and to Parliament.

British North America Act

Macdonald wanted to call the new country the Kingdom of Canada. But the word kingdom was viewed with suspicion in the United States. And the British did not want to provoke the Americans. So it was changed to “Dominion.” This was Tilley’s idea. It was inspired by a line from the Bible that refers to God’s dominion. It reads, “He shall have dominion also from sea to sea, and from the river unto the ends of the earth.”

A final draft of the bill that made Canada’s confederation official was given to Queen Victoria on 11 February 1867. It was read in the House of Lords the next day. It passed through three readings in that house by the end of the month. It then passed through three readings in the House of Commons in two weeks. There was very little debate. The most notable event during this time was the marriage of John A. Macdonald to his second wife, Agnes Bernard. Their wedding was on 16 February.

The British North America Act (now called the Constitution Act, 1867) passed through the British House of Commons and House of Lords. It received Queen Victoria’s Royal Assent on 29 March 1867. The delegates then returned home. On 1 July 1867, the former colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada (now Ontario and Quebec) officially became the Dominion of Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom