Innu, which means “people” in the Innu language, is the predominant term used to describe all Innu. Some groups maintain the use of one of two older terms: Montagnais (French for “mountain people”), usually applied to groups in forested, more southern communities, and Naskapi, which refers to far northern groups who inhabit the barren lands of the subarctic. In the 2021 census, 18,620 people identified as having Innu ancestry, with 17,970 people claiming Innu/Montagnais ancestry and 735 people claiming Naskapi ancestry.

Population and Territory

Innu traditional territory includes the vast boreal territory on the Labrador Peninsula known as Nitassinan. They are distinct from but closely related to Eastern Cree groups that inhabit the western portion of the Labrador Peninsula.

Though Innu were traditionally nomadic, contemporary communities are largely sedentary, the product of government policies to integrate Indigenous peoples into the global economy through forced relocation. Groups are widely dispersed across a huge area of land. Many communities are remote, but relatively accessible. For example, Uashat and Mani-utenam are in and around Sept-Îles, Quebec, along the north shore of the St. Lawrence. Others are far more remote, like the communities of Matimekush-Lac-John and Kawawachikamach around Schefferville, Québec, north of Labrador.

Innu communities in Quebec include Pessamit, Kawawachikamach, Unamen Shipu, Essipit, Uashat mak Mani-utenam (the collective name for the two Sept-Îles communities), Mashteuiatsh, Ekuanitshit, Nutashkuan, Pakua Shipu, and Matimekush-Lac-John (Schefferville). The two largest Innu communities in Labrador are the Mushuau Innu in Natuashish and the Sheshatshiu Innu in Tshishe-shastshit.

Pre-colonial Life

Innu traditionally hunted and fished across the vast boreal territory known as Nitassinan on the Labrador Peninsula. Innu hunted game animals like caribou in the eastern and northern areas, moose in the west, as well as beaver, bear, lake fish and salmon. In addition to hunting game, Innu fished for eels and fish, hunted seals, and gathered roots, berries and maple sap. They developed trade networks with other Indigenous groups such as the Huron-Wendat.

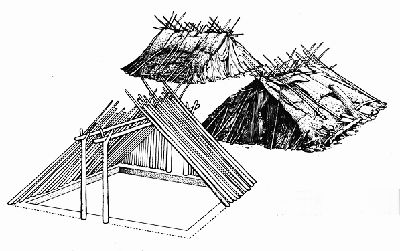

The Innu travelled in much the same way as their Algonquian relatives, using the canoe in summer, and snowshoes and toboggans in winter. In addition, Innu lived in wigwams made of birchbark in the south and caribou hide in the north. Social groups revolved around the seasons. Several families would come together into winter hunting camps, while larger gatherings occurred in the summer, providing an opportunity for festivities and socializing.

Traditional hunting techniques used every part of the caribou; craft makers decorated skins with painted or quill designs to make clothing of many kinds, or made drums for celebrations and sacred singing. The cracks and fissures in a burnt caribou shoulder blade were believed to foretell the location of game. Belief in animal spirits played a major role in the hunt. People gained status mainly through the ability to make gifts of meat to others. After the hunt, communities would hold a ceremonial feast ( makushan) of caribou fat and bone marrow. The feast included drumming and songs sung to the animal spirits. Much of the ancestral religion is recorded in legends and songs.

Culture

The Innu have a rich culture that includes traditional art, music, dance and sacred ceremonies. While Innu culture (and Indigenous cultures, more broadly) has been threatened by the forces of colonization, several programs today support the survival of Innu cultural life. Nametau Innu, for example, is a project that aims to pass skills and traditional knowledge from Elders to youth. The books of Innu author, An Antane Kapesh, and the Innu-aimun (Innu language) recordings by pop music duo Kashtin, show that Innu culture continues to adapt and thrive. Since 1985, Uashat mak Mani-utenam has hosted a yearly summer festival of Indigenous music, Innu Nikamu. Each year, more than 10,000 festival-goers celebrate and connect with traditional music and artists. (See also Indigenous Art in Canada.)

Religion

Pre-colonial Innu religion was a personal endeavour and encouraged the cultivation of respect for animals. The caribou was the most revered animal as it provided practically all the necessities of life. Shamans performed Shaking Tent rites, and hunters appeased animal spirits by placing offerings of bones and skulls in trees or on raised platforms.

The arrival of European missionaries drastically altered ways of life for the Innu. Early in the relationship, Christian texts were translated into the Innu language and missionaries became actively involved in Innu spiritual and cultural life. In the 18th century, missionaries in association with community members helped to develop a standard orthography for Innu-aimun, in addition to their efforts to convert the population to Christianity. While many contemporary Innu communities retain these religious affiliations, traditional beliefs persist in some communities.

Language

Innu-aimun (the Innu language) is part of the Algonquian language family. It is spoken by people traditionally known as Montagnais, while Iyuw Iyimuun is a dialect spoken by the Naskapi. The language is widely spoken among communities and is supported by projects like the Innu Language Project, which promotes Innu-aimun and Innu culture through learning resources. The two languages are similar, but variances in dialects and orthography (spelling) exist. For instance, some communities may use syllabics, while others may use Latin script. Contemporary Innu communities are also largely fluent in either French or English. In the 2021 census, 9,405 people reported Innu (Montagnais) as their mother tongue, while an additional 735 people reported Naskapi. In that same census, 10,595 people claimed knowledge of Innu (Montagnais) and 1,010 people reported knowledge of Naskapi. (See also Indigenous Languages in Canada.)

Colonial History

Although the Innu briefly fought the Inuit, the Haudenosaunee, the Mi’kmaq and the Abenaki, they were not a warlike group, and at least some hostility was a side effect of European contact. In the Tadoussac region, the Innu were military allies of the French in their wars with the British and their Indigenous allies. (See also Iroquois Wars.) Champlain formed an alliance with an Innu group in 1603, laying a foundation for French-Indigenous relations to come.

Before the 19th century, most contact between the northern Innu and Europeans was indirect, generally by trade through neighbouring Cree and southern Innu intermediaries. Life depended on the movements of the barren-ground caribou. Starting in 1830, the Hudson's Bay Company opened posts in this northern region, supplied first from Fort Chimo and later from North West River, Labrador. For two centuries the fur trade was the focus of Innu-European relations. Trade at posts in the Gulf of St. Lawrence were monopolies first of France and later Britain and were leased to private traders. By the mid-19th century, most areas were over-hunted, and the southern Innu needed assistance from missionaries and the government to survive. Soon, commercial forestry increased their difficulties, and they were excluded from salmon rivers, which were leased by clubs and individuals. The fur trade had disastrous results for the Innu because the trapping lifestyle did not allow the flexibility needed to follow nomadic caribou herds.

As with many Indigenous peoples during their early contact with Europeans, the Innu population was devastated by smallpox, the Spanish flu, tuberculosis, syphilis, scarlet fever, whooping cough, measles and other diseases. Large numbers of people also died of starvation. The shift away from traditional ways of living meant a reliance on the wage economy and government intervention. For some, this meant forced relocation to communities where social problems only worsened.

Though Innu were forcibly settled into communities, they were not party to any treaty negotiations, and they were not recognized as having Aboriginal title to their lands. Though strong pressures were placed on the Innu to abandon nomadic life, hunting and fishing remain important within their communities. In response to forced settlement, many Innu communities developed organizations to advocate for their Indigenous rights. Beginning in the middle of the 20th century, the federal government forced Innu and Inuit to relocate to permanent settlements, which resulted in social and economic hardships. (See also Inuit High Arctic Relocations in Canada.)

Political Organization

Two tribal councils represent Innu groups in Québec: Le Conseil Tribal Mamuitun (incorporated in 1991) represents Mashteuiatsh, Essipit, Pessamit, Uashat, Mani-utenam and Matimekush; while Mamit Innuat (founded in 1982, incorporated in 1988) represents Ekuanitshit, Nutashkuan, Pakua Shipu and Unamen Shipu. The Innu Nation represents the two Labrador communities. The groups continue to press for settlement of their land claims and protection from the impact of forestry, hydroelectric dams, roads, and low-level military flights and mines, such as those in Voisey’s Bay, Labrador.

Treaties and Self-government

Originally excluded from the Agreement in Principle leading to the James Bay Agreement in 1975, the Innu Nation negotiated a separate agreement in 1978, known as the Northeastern Québec Agreement, which provided the Naskapi of Kawawachikamach (Schefferville) with some self-government concessions and $9 million over 20 years in exchange for development rights.

Contemporary Life

Isolated communities have suffered from high rates of alcoholism, substance abuse and suicide. In 1993, the Innu of Davis Inlet (Utshimassits) attracted the attention of the world’s press over a gas-sniffing epidemic. (See also Gas Sniffing in Labrador.) The children involved recovered but the incident was seen as representative of poor conditions in Indigenous communities in Canada. In 2001, the Government of Canada, the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Labrador Innu developed the Labrador Innu Comprehensive Healing Strategy to address some of the problems within the Innu communities. In 2002, approximately 680 people from Davis Inlet relocated to Natuashish, west of the original community. In 2008, Natuashish residents voted to ban alcohol on their reserve.

In 2002, the Innu Nation successfully lobbied the federal government to be recognized as Status Indians, giving them access to various federal programs and services under the Indian Act. The communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu, both located in Newfoundland and Labrador, were established as reserves in 2003 and 2006 respectively.

Since 2005, Tshiuetin Rail Transportation Inc., owned and operated by the following communities — Innu Takuaikan Uashat Mak Mani-Utenam, Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach, and Nation Innu Matimekush — has provided a passenger rail link between Emeril (Labrador) and Schefferville (Quebec).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom