“Peace, order and good government” is a phrase that is used in section 91 of the British North America Act of 1867 (now called the Constitution Act, 1867). It offers a vague and broad definition of the Canadian Parliament’s lawmaking authority over provincial matters. Since Confederation, it has caused tensions between federal and provincial governments over the distribution of powers. The phrase has also taken on a value of its own with Canadians beyond its constitutional purpose. It has come to be seen as the Canadian counterpart to the American “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and the French “liberty, equality, fraternity.”

Background

The phrase “peace, order and good government” was used in a British colonial context to give local governments the power to make laws. The New Zealand Constitution Act of 1852, the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act of 1900, the South Africa Act of 1909 and the Government of Ireland Act of 1920 all use the phrase. In Canada, variants such as “peace, welfare and good government” appear in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the Quebec Act of 1774, the Constitutional Act, 1791, and the Act of Union in 1840–41. “Peace, order and good government” first appeared in Canada with the Proclamation of British Columbia in 1858.

Confederation

Following years of consultation and deliberation, the Constitution Act, 1867 was approved by the British Parliament in 1867. The Act merged the Province of Canada (present-day Ontario and Quebec), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia into a federal Dominion within the British Commonwealth. The new country was to be run by the Government of Canada with limited interference from British authorities. It would have its own House of Commons, Senate and judicial system.

The power to create laws was divided between the federal and provincial governments. Due to the regionalism that destabilized pre-Confederation politics, the Canadian government adopted a federal structure. This was intended to preserve a degree of local autonomy in the provinces. (See also: Distribution of Powers; Federal-Provincial Relations.)

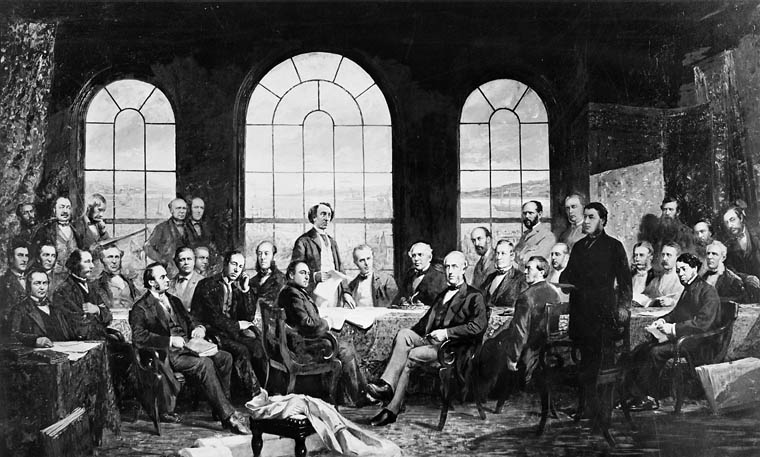

La Conférence de Québec en 1864, tenue pour établir les bases d'une union des provinces de l'Amérique du Nord britannique.

Distribution of Powers

Sections 91 through 95 make up Part VI of the Constitution Act, 1867. Part VI details the distribution of powers between the federal government and the provinces. The Fathers of Confederation intended to create a system in which jurisdiction over national affairs fell to the federal government. Local affairs would be the responsibility of provincial governments. Section 91 defines the jurisdiction of the federal government, giving it the power “to make laws for the peace, order and good government of Canada” in all matters not exclusively the jurisdiction of the provinces.

Section 92 defines the areas of provincial powers. These include provincial taxation, property, most contracts and torts, local works, prisons, charitable institutions, and hospitals. If a need arises for legislation whose jurisdiction is not defined by sections 91 or 92, then the principle of “peace, order and good government” gives responsibility to the federal government.

Interpretation

The broad scope of the phrase “peace, order and good government” can be interpreted to mean that the federal government should have authority over any matters not immediately pertaining to the provinces. In practice, federal authority has been interpreted by the courts as related to four areas: residual; emergency; national concern; and federal paramountcy.

Residual Branch

The residual branch pertains to any matter not described in sections 91 and 92. This branch is rarely used. Matters not in existence at the time of Confederation were not typically the jurisdiction of the federal government. However, the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed the federal government’s authority over aeronautics in 1952, in Johannesson v. West St Paul (Rural Municipality of). That case set the precedence for modern interpretations of “peace, order and good government.”

Emergency Branch

In exceptional circumstances, the federal government may invoke a state of emergency. (See also Emergency Preparedness.) This grants Parliament special powers. These powers allow the federal government to infringe on provincial jurisdiction when the country is facing an existential crisis. Such emergency powers are only to last as long as the emergency itself.

During the First World War, the federal government passed the War Measures Act. It gave the federal Cabinet sweeping powers over almost any matter and allowed it to violate civil liberties. (See also: Internment in Canada; Ukrainian Internment in Canada; Internment of Japanese Canadians.) In 1988, the War Measures Act was repealed and replaced by the Emergencies Act. It authorizes “the taking of special temporary measures to ensure safety and security during national emergencies and to amend other Acts in consequence thereof.”

The Emergencies Act created more limited and specific powers for the federal government to deal with security emergencies of five different types: national emergencies; public welfare emergencies; public order emergencies; international emergencies; and war emergencies. Under the Act, Cabinet orders and regulations must be reviewed by Parliament. This means the Cabinet cannot act on its own, unlike under the War Measures Act. The Emergencies Act also notes that government actions are subject to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Canadian Bill of Rights.

National Concern Branch

Under the national concern branch, the federal government can pass legislation on matters described in section 92 when those matters affect the principle of “peace, order and good government.” In 1896 and 1946, two cases related to the prohibition of alcohol provided examples of local matters concerning the federal government. In 1988, the Supreme Court ruled that this doctrine applies to matters that did not exist in 1867 (such as matters related to polluting the ocean), and to provincial matters that are of national concern but are not yet emergencies.

Federal Paramountcy Branch

If there are overlapping federal and provincial laws, the legislation passed by the federal Parliament takes precedence. Historically, this has meant that in the case of conflict or overlap, federal laws were used. However, in November 2015, the Supreme Court held that federal paramountcy should only apply if federal and provincial legislation directly contradict one another.

Significance

The phrase “peace, order and good government” has become key to mediating the distribution of powers between federal and provincial governments. Canada was initially intended to have a strong, centralized government. (See Federalism.) Over the course of the 20th century, legal interpretations of “peace, order and good government” more clearly defined the limits of federal authority over the provinces.

The idea of national identity expressed by “peace, order and good government” is part of a set of beliefs that makes up the myth of Canada as the Peaceable Kingdom. The phrase “peace, order and good government” has taken on a value of its own with Canadians beyond its constitutional purpose. It has come to be seen as the Canadian counterpart to the American “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and the French “liberty, equality, fraternity.”

See also: Constitutional History; Constitutional Law; Constitutional Monarchy; Constitution Act, 1867; Constitution Act, 1867 Document; Statute of Westminster; Statute of Westminster, 1931 Document; Patriation Reference; Patriation of the Constitution; Constitution Act, 1982; Constitution Act, 1982 Document.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom