Quillwork refers to the Indigenous art of using coloured porcupine quills to decorate various items such as clothing, bags, medicine bundles and regalia. Quillwork pieces have been preserved in museums and cultural centres across North America. Now considered a rare artform, elders and specialized artists use quillwork to promote cultural traditions.

What is Quillwork?

Quillwork is the art of using dyed porcupine quills, which are often wrapped, woven and sewn through birch paper, to decorate items such as buckskin clothing, birchbark boxes, calumets, knife sheaths, medicine bundles, parfleches, drums, tipi covers and moccasins.

Quillwork was sacred in some Indigenous communities. Among the Blackfoot, only a specialized group of women performed quillwork, and when they did, they had to also recite prayers or wear certain ornaments or body paint, depending on the nation. In Mi’kmaq culture, quillwork was also traditionally performed by women, and was believed to confer spiritual power. (See also Religion and Spirituality of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Around the mid-1800s, quills were replaced in popularity by glass beads, which were easier to find and use, and were also available in a variety of colours.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Mi’kmaq were well-known for their quillwork pieces, and as a result, some Europeans called them the “porcupine people.”

Making Quillwork

The first step in making quillwork was to acquire quills, whether from porcupines directly or from trading with Indigenous communities that had greater access to the animal. The next step was to clean the quills and dye them using natural colourants from flower petals, roots and vegetables, fruits, and the like. The process of harvesting and preparing the quills could take several days.

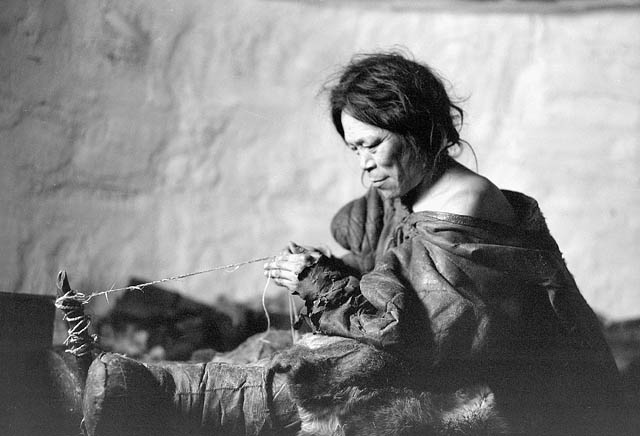

Before sewing or weaving, women often moistened and flattened the quills by drawing them between the teeth or over the thumbnail, making them more pliable. Sewing and weaving patterns depended on the nation; among the Mi’kmaq, for example, quillwork almost always took on a geometric design.

For quillwork on birchbark (see also Birch), women punctured holes in the bark with an awl (a narrow tool with a pointed end) and then inserted the quills inside. This method was used to decorate boxes, mats and headpieces.

Cultural Significance

Quillwork is more than just a fine example of Indigenous artisanry, it holds cultural significance as part of traditional knowledge systems. These traditions have

been threatened over time by the processes of colonization. Quillwork is now a rare artform, but some Indigenous elders and artists are trying to preserve it

through community-led education about quilling. Mi’kmaq artist Beverly Julian actively educates community members about this traditional art. Similarly, Dene artist Lucy Yakeleya offers workshops to those who want to learn more about quillwork. Through efforts such as these, Indigenous peoples aim to preserve and promote this culturally

significant craft.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom