Early Life and Education

Rita Joe was born to Joseph and Annie Bernard of the Mi’kmaq nation. She spent her early childhood on a reserve at Whycocomagh on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia. Rita’s mother died when she was only five; subsequently she was sent to live with foster families. At the age of nine, Rita returned to her reserve to live with her father and siblings, Annabel, Soln, Roddy and Matt. About a year later, Rita’s father died, once again forcing her into foster homes. At the age of 12, Rita entered the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School on mainland Nova Scotia (see Residential Schools). Like many Indigenous children, Rita was forbidden to speak her Mi’kmaq language in the school that she likened to the military. When she had completed school, Rita had to re-learn her native language by talking to Mi’kmaq speakers (see Indigenous Languages in Canada).

Rita worked various jobs in Nova Scotia before moving to Boston. It was there that she met Frank Joe, her future husband. Frank was originally from Eskasoni, a Mi’kmaq First Nation close to Rita’s home reserve. Rita later returned to Cape Breton to live on the Eskasoni reserve, where she and Frank raised 10 children, including two foster sons.

After Rita’s literary career took off in the 1970s, she went back to school to complete high school and take a course in business education. Her husband Frank also returned to school and received a bachelor of education as well as a degree in sociology.

Rita Joe’s Poetry

Rita Joe’s experiences as a Mi’kmaq person in Canada deeply influenced her works. In her writing, Joe sought to challenge the negative messages she encountered about her Indigenous identity at residential school and as an adult in the books her own children were reading. In the prologue to her memoir, Song of Rita Joe (1996), she states: “My greatest wish is that there will be more writing from my people, and that our children will read it. I have said again and again that our history would be different if it had been expressed by us.”

Although Joe began writing in the late 1960s, her first collection of poetry, Poems of Rita Joe, was published in 1978. Her second volume, Song of Eskasoni: More Poems of Rita Joe appeared in 1988 and contained one of her most well-known poems, “I Lost My Talk.” The poem speaks about how residential school altered her very identity: “I speak like you / I think like you / I create like you.” At the end of the poem, Joe speaks about the possibility for reconciliation and reclaiming lost identity: “So gently I offer my hand and ask, / Let me find my talk / So I can teach you about me.” Four lines of Joe’s famous poem were included in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report on residential schools in Canada: “I lost my talk / The talk you took away. / When I was a little girl / At Shubenacadie School.”

Her third book, Lnu and Indians We’re Called, was released in 1991. Rita Joe’s poetry is included in the 1994 anthology Kelusultiek: Original Women’s Voices of Atlantic Canada. Kelusultiek, which takes its title from a poem by Rita Joe and translates as “we speak,” also includes the lyrics and music to one of her best known songs, “Oka Song,” as well as another well-known work, “The Drumbeat Is the Heartbeat of the Nation.” The “Oka Song” was written in response to the 1990 land dispute and armed standoff at Oka (see Oka Crisis). Rita Joe read “The Drumbeat Is the Heartbeat of the Nation” to dignitaries on Treaty Day in October 1992.

Her memoir, Song of Rita Joe: Autobiography of a Mi’kmaq Poet, was published in 1996. She relates both the terrible difficulties and the amazing accomplishments of her life in unassuming but compelling prose. Her autobiography also includes poetry, music and photographs.

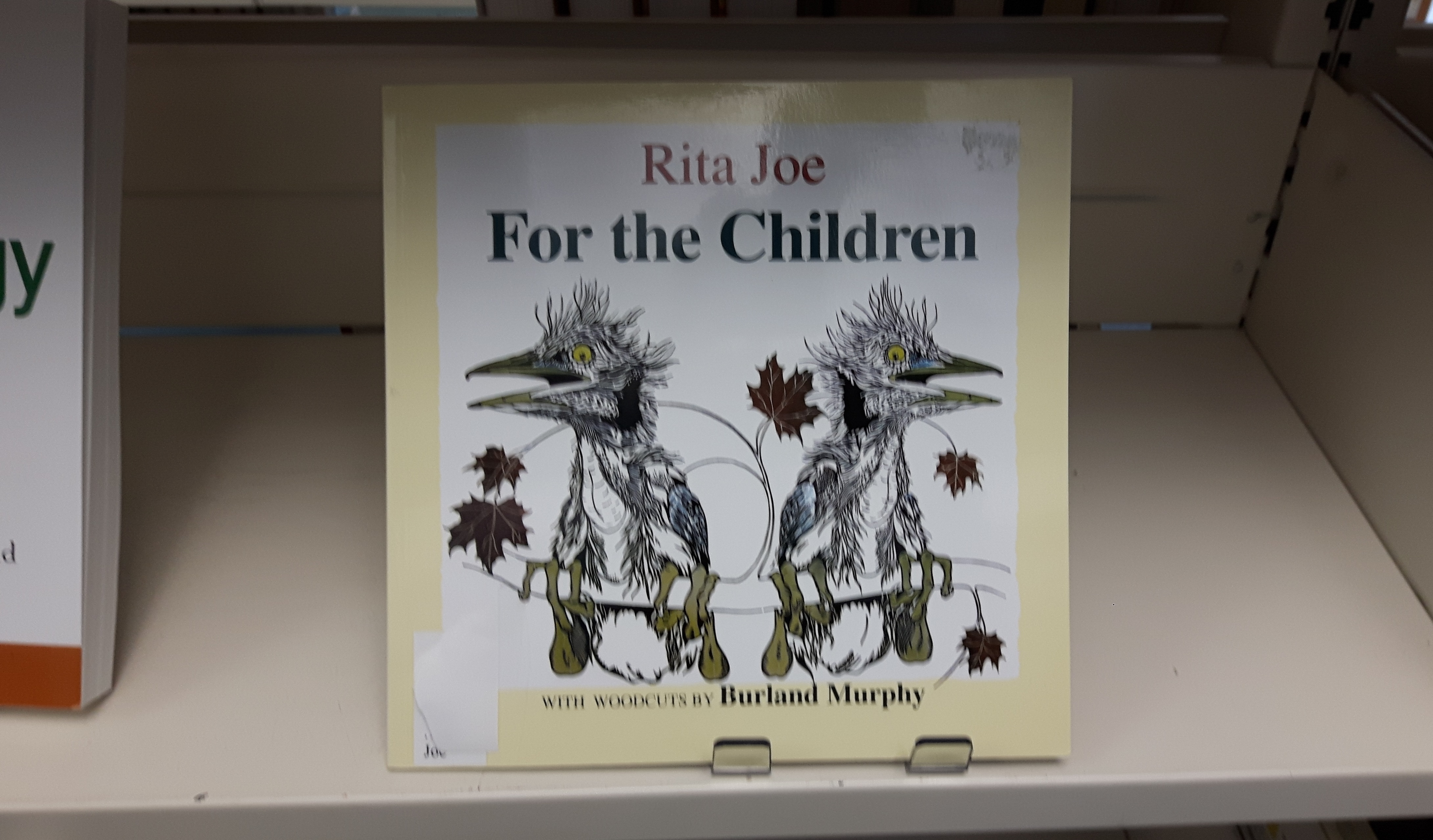

Rita Joe’s now out-of-print first collection can also be found in We are the Dreamers: Recent and Early Poetry (1999). Her poems cover a wide range of subjects, from the domestic to the spiritual. Her language is blunt but lyrical, and she captures both the sorrow and joy of life. Joe co-edited, with Lesley Choyce, and contributed to The Mi’kmaq Anthology (1997) — a collection of stories, poems and essays written by Mi’kmaq people.

Works Inspired by Rita Joe: Film, Music and the Arts

Rita Joe is the subject of a 1993 documentary titled Song of Eskasoni. Directed by Brian Guns and narrated by Rita Joe, the film celebrates Mi’kmaq culture as reflected in her poetry.

In January 2016, the National Arts Centre (NAC) in Ottawa premiered I Lost My Talk, a multimedia performance based on Joe’s poem of the same name. The NAC orchestra performed music composed by John Estacio. A film directed by Barbara Willis Sweete accompanied the music. Shown on screens surrounding the stage, the film featured Indigenous dancers interpreting the poem and music in Killbear Provincial Park, near Parry Sound. Actor Monique Mojica of Guna and Rappahannock ancestry played Rita Joe on stage as she recited the poem. Produced and directed by Donna Feore, the performance shone a light on the legacy of residential schools in Canada. Commissioned by the family of former prime minister Joe Clark, who was an honourary witness for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the performance also sought to encourage discussion about reconciliation.

“I Lost My Talk” also inspired the Rita Joe National Song Project (2016), a program of the NAC that encouraged students to create a song based on what Rita Joe’s poem means to them. Young artists from five selected communities across Canada sent in professional audio and visual recordings of their songs to the NAC to be showcased at the same time as the 2016 premiere of the performance based on Rita Joe’s poem. The performance also featured live entertainment by youth from Maniwaki’s Kitigan Zibi Kikinamadinan School in Maniwaki and ABMHS High School in Eskasoni, Cape Breton.

Publications

- Poems of Rita Joe (1978)

- Song of Eskasoni (1988)

- Lnu and Indians We’re Called (1991)

- Kelusultiek: Original Women’s Voices of Atlantic Canada (1994)

- Song of Rita Joe: Autobiography of a Mi’kmaq Poet (1996)

- The Mi’kmaq Anthology (1997) (co-edited with Lesley Choyce)

- We are the Dreamers (1999)

Awards and Honours

In addition to a number of honorary doctorates, Rita Joe has received the following awards and honours:

- Atlantic Writing Competition (1975)

- Member of the Order of Canada (1989)

- Member of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada (1992)

- National Aboriginal Achievement Award (1997) (now called the Indspire Award)

Significance

Upon her appointment to the Order of Canada, Rita Joe was described as a “true ambassador for her people, promoting [Indigenous] art and culture across Canada and in the United States.” More affectionately known by some as the “gentle warrior” or the “warrior poet,” Rita Joe is remembered for the way her poems expose truths about residential school and about growing up Indigenous in Canada, while also speaking about peace, reconciliation and healing.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom