Historical Context

The discovery of gold in present-day British Columbia’s Fraser River valley in 1857 initiated the beginning of significant Chinese immigration to the region, which increased when thousands of Chinese workers arrived in the early 1880s to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. By the time the railway was completed in 1885, fervent anti-Chinese racism in British Columbia impelled the introduction of the federal Chinese Head Tax that year. (See also Anti-Asian Racism.) Originally set at $50, this entry tax for Chinese immigrants was eventually increased to $500, and remained in effect until the introduction of the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which barred most new Chinese settlement in Canada. While 39,000 people of Chinese origin lived in Canada in 1921, Chinese exclusion halted population growth to approximately 32,000 by the time the Act was repealed in 1947.

Japanese immigration began in 1877 and increased significantly in the early 20th century, when thousands arrived in British Columbia. The province’s resident population believed that Japanese economic competitiveness and Japan’s rising global status made them a greater threat to Canadian society than the Chinese. After aggressive anti-Japanese lobbying by the province, in 1908 Canada negotiated the Hayashi-Lemieux “Gentleman’s Agreement,” in which Japan’s government agreed to limit the emigration of its male citizens to Canada to 400 per annum. This number was later decreased to 150, and the policy remained in effect until the Second World War brought the end of Japanese immigration entirely. By this time, approximately 23,000 Japanese lived in Canada, most residing in British Columbia.

South Asians, mainly Sikhs from India’s Punjab region, began arriving in significant numbers in 1906, and within two years a total of 5,000 had arrived in British Columbia (see Sikhism in Canada). Responding to anti-Indian racism and populist concerns that South Asians were taking jobs from white workers, in 1908 Canada’s government introduced an order in council prohibiting immigrants who had not arrived by continuous journey from their land of origin. Since this method of transportation was impossible from India, the act effectively ended South Asian immigration until 1947, when less than 2,500 South Asians remained in the province.

While Asian newcomers to Canada initially settled on the Pacific coast, by the late 19th century many had crossed the country by rail to Ontario and Quebec, where they faced similar, if less sustained, opposition to their settlement. For example, Ontario was the first province to prohibit Chinese males from employing “any female white person” in a laundry, restaurant or factory, a law which was only revoked in 1947.

Many Canadians may not have heard of Madhu Verma but her almost fifty years of social activism has greatly shaped the current landscape of Fredericton, N.B. and Canada's East Coast.

Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Work

The thousands of male Chinese workers who had built the Canadian Pacific Railway had few job options after its completion in 1885. Some found work in construction or agriculture, but British Columbia’s labour unions like the Knights of Labor and Trades and Labour Congress excluded them from their ranks, which limited Chinese opportunities for gainful employment in these sectors. While many Chinese had mined during the Fraser River Gold Rush, British Columbia’s 1897 Inspection of Metalliferous Mines Act barred Chinese and Japanese workers from the metal mining industry. In 1898, Asians were excluded from public works projects, and a series of subsequent laws prohibited their hiring by the province’s smaller railway companies. While many South Asians found work in the lumber industry after their arrival in 1906, a law passed shortly thereafter barred all Asians from holding logging licenses.

Despite the numerous legislative barriers to their employment in British Columbia, many Asian workers chose to remain in the province, where they found work in domestic service or other fields traditionally dominated by white women, or secured jobs as launderers, cooks, waiters and store clerks. After Ontario barred Chinese males from hiring white females in 1914 – a provision which was expanded in 1929 to prohibit Chinese males from managing or supervising white women – Saskatchewan passed a similar law which forbade “any white woman or girl” from working in “any restaurant, laundry or other place of business” owned “by any Japanese, Chinaman or other Oriental person.” In 1919, British Columbia’s legislature followed suit to “protect” white female workers from exploitation by Asian men. This law, which was not repealed until 1968, effectively instituted Asian segregation by separating white female and Asian male workers.

With so many doors closed to them in British Columbia, some Asians returned to their home countries, but most Chinese found themselves stranded in Canada after CPR contractor Andrew Onderdonk reneged on a promise to ship them back to their home country after the railway’s completion. To find new opportunities and escape systemic discrimination on the Pacific coast, many ex-railway workers headed east across the Rocky Mountains. In 1877, Jos Song Long opened Montreal’s first Chinese-owned business, a laundry establishment on Craig Street, which along with Rue De La Gauchetière eventually became the heart of the Montreal Chinatown neighbourhood. Over the following decade, Chinese immigrants, who were mainly from China’s Canton region, began to settle in the district, where they later opened restaurants, laundries and other service-oriented businesses. However, when shop owners were unable to pay Montreal’s prohibitive licensing fees, which they argued were discriminatory, many were fined or imprisoned, while others were forced to close their businesses permanently.

Toronto’s Chinatown district grew much more slowly than Montreal’s, but after its establishment on Elisabeth Street after 1915, journalists, politicians and others began to criticize the living and working conditions of the city’s 1,000 Chinese residents. For example, Saturday Night magazine and the Globe newspaper editorialized about the dangers of Chinese labour in Ontario’s capital city, where Chinese merchants and service people operated in overcrowded and unsanitary buildings. Other impoverished newcomers, such as Jewish and Italian immigrants, conducted businesses in similar conditions, but their establishments were not seen as the same threat to the city’s industry or social structure as the “Asiatic Peril” was. Arlene Chan points out that this negative attention had the opposite effect than journalists and other Toronto observers intended: instead of closing their businesses and moving away to escape discrimination, shop owners and residents of Chinatown chose to stay and build a strong, supportive expat community within the neighbourhood’s boundaries.

Housing and Health Care

From its beginning in the 1880s, Vancouver’s Chinatown became an important cultural centre for Chinese men and families, but it also became a magnet for anti-Chinese sentiment. Frequent police raids and health inspections of Chinatown living quarters drove many residents to look for housing elsewhere in the city. When they did, they found few property owners willing to rent to them or to the city’s Japanese and South Asian residents. The lack of statutory protections against rental discrimination meant that Asians became increasingly spatially separated from whites, living in ethnic neighbourhoods wherever they settled in the province.

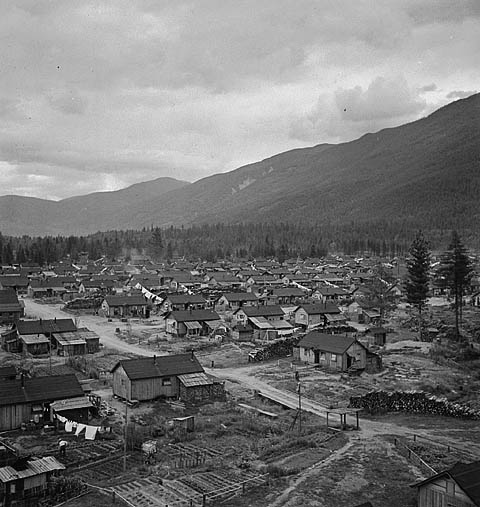

Asians who could afford to buy homes or farms became popular targets of anti-Asian activists, who aggressively lobbied for the province to adopt its own version of California’s “Alien Land Law” of 1913. While this law – which targeted Japanese people by banning “aliens ineligible to citizenship” from owning agricultural land in that state – was never implemented in British Columbia, private land titles often include clauses which forbid land sales to Asians. For example, West Vancouver’s “British Properties” homes, which were developed by the heirs to the Guinness beer fortune, explicitly forbade deed transfers to anyone of “Asiatic descent.” However, the most obvious example of Asian segregation in housing occurred during Japanese Internment in the Second World War, when the Canadian government forcibly removed more than 22,000 Japanese Canadians from their homes and imprisoned them in internment camps in British Columbia. Here they lived apart from other ethnic groups until they were permitted to return to the Pacific coast in 1949.

The creation and growth of Asian communities in Canada in the 19th and early 20th centuries also had significant consequences for medical inspection and health care. During a 1907 outbreak of bubonic plague in San Francisco, California, the BC legislature ordered that “all sick Chinese, Japanese, Sikhs or other Orientals” inform local health authorities of their condition, and Vancouver’s medical inspectors uniquely targeted Asian neighbourhoods in their search for plague victims. In Montreal during the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918, civic officials frequently excluded Chinese patients from the city’s “white” hospitals, leading to the Chinese Benevolent Association’s establishment of a Chinese hospital. In both epidemics, Euro-Canadian associations between Asians and infectious disease were predicated on racist stereotypes of unhygienic “Orientals.” Journalists, politicians and others often portrayed these people as dirty, unsanitary and a threat to public health. (See also Anti-Asian Racism.)

Education

Most first-wave Asian immigrants were male economic migrants who sought temporary work in British Columbia’s natural resource industries. However, many of those who chose to settle permanently in Canada eventually sent for their families to join them. While expatriate community organizations offered English classes to young pupils, many Chinese, Japanese and South Asian children attended public schools, especially in Vancouver and Victoria. These cities partially segregated Chinese students, who were the majority of Asian students at the schools, by putting them into Chinese-only classes at the primary levels and holding back older students who could not speak English at the level of white students. Despite these measures, many parents of white children and other community members lobbied their school boards to address what they saw as the growing problem of “race mixing” between Chinese and white students on the playground. Since provincial law banned Asians from becoming or voting for school board trustees, the Chinese community had no voice in debates over segregation or other aspects of their children’s education. (See also Anti-Asian Racism.)

In July 1922, Victoria’s public school board voted to implement the full segregation of Chinese students by ordering that they attend one of two Chinese-only schools in the city’s North Ward district. To bar teenaged children recently arrived from China, whose English skills placed them in lower grades than their white peers, all primary students over the age of 12 were excluded from school, as were students over the age of 17. Despite anti-segregation protests by Chinese parents and others – and the concerns of residents living near the two schools selected for the program, who wanted them to be in Chinatown instead – the board ordered that segregation commence in September. However, the Chinese Canadian Club and Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association organized a student’s strike, which began on the first day of classes and continued until the board finally agreed to reintegrate the students at their regular schools the following fall.

Politics and Citizenship

In 1872, shortly after the arrival of first wave Chinese immigrants in British Columbia, the province banned Chinese people from voting in provincial elections, and later excluded them from running for election to the province’s legislature. Japanese were added to the non-voter’s list in 1895, as were South Asians in 1908. While an 1885 federal law barred Chinese voters from voting in federal elections, the 1920 Dominion Elections Act effectively extended the ban to Japanese, South Asians and other Asians by denying the federal franchise to any group prohibited from voting in provincial elections. Despite extensive campaigning by multiple Asian groups in the province, and the high-profile 1922 visit of Indian politician V.S. Srinivasa Sastri, who asked federal and provincial officials to reverse these laws and permit South Asians to vote in Canada, Asians continued to be excluded from the ballot box until after the Second World War. Finally, in 1947, Chinese and South Asians were granted the right to vote in all elections, and Japanese Canadians were the last Asian group to receive the franchise in 1949.

Today, persons of Asian descent form a key part of Canada’s society, participating in all levels of politics and governance and playing important social, economic, and religious roles across the country. They also represent a significant proportion of our nation’s visible minorities, with the 2016 census indicating that 1,924,635 individuals self-identify as South Asian Canadians, 1,577,060 identify as Chinese Canadians, and many others as Korean, Japanese, or other Canadians of Asian origin. While discriminatory barriers to Asian settlement, labour, political engagement and social participation have been removed, many Asian newcomers to Canada live in poverty and are concentrated in ethnic enclaves in low-income and unsafe neighbourhoods in the nation’s urban centres (see Residential Segregation). The nation’s federal, provincial and municipal governments and private/charitable organizations have taken important steps to provide second language training, adult education and job training for Asian people and other newcomers, but many Asian Canadians still face considerable financial and other barriers to their successful integration into our nation’s economy and society.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom