Sylvia Estes Stark, pioneer (born 1839 in Clay County, Missouri, US; died 7 November 1944 in Fruitvale, Salt Spring Island, British Columbia). Born into enslavement, Sylvia Stark was one of more than 600 Black Americans who emigrated to British Columbia in 1858 at the invitation of Governor James Douglas. She was one of the original settlers on Salt Spring Island.

Sylvia Stark was one of more than 600 Black Americans who emigrated to British Columbia in 1858. She was one of the original settlers on Salt Spring Island. Photo taken at the home of Naidine Sims in 1890.

(courtesy Salt Spring Island

Archives/Estes-Stark

Collection/989024013)

Early Life

Sylvia Estes was born into enslavement in Clay County, Missouri. Her mother, Hannah, was a cook in a bakery owned by Charles Leopold, and her father, Howard, was a cowboy for Thomas Estes. Sylvia’s earliest memories were of forced labour. Although an 1847 ordinance forbade Black children from learning to read or write in the state of Missouri, Sylvia secretly learned to read by listening to the lessons received by the Leopold children.

In 1849, Sylvia’s father accompanied Thomas Estes’ two sons to California, where they planned to sell their herd of cattle. He was allowed to prospect for gold while there and used the money to purchase his family’s freedom. Howard paid $1,000 each for his freedom and that of his wife, Hannah, and their son, Jackson. He purchased Sylvia’s freedom for $900. The total of $3,900 was a large amount for the time. The annual stipend for an American congressman in the 1850s was $3,000.

Traveling West

Howard and Hannah Estes and their two children settled initially on a 40-acre farm in Clay County, Missouri. But as Sylvia’s daughter Marie Albertina later wrote, “their new-found freedom was disturbed by night riders called the Klu-Kluks [Klan]. They were going about beating and kidnapping ‘colored’ people, terrorizing them." The Estes family decided to move to California. Howard and Hannah found employment as a cowboy and cook in a wagon train traveling west in 1851. Twelve-year-old Sylvia found the journey fascinating and later shared her memories of buffalo stampedes, coyotes and prairie dogs with her children.

In California, the Estes family settled on a small fruit and vegetable farm in Placerville, near Sacramento. Howard worked as cowboy and miner and Hannah worked as a laundress.

Marriage and Children

In September 1855, at the age of 16, Sylvia married Louis Stark (1816–95), the owner of a dairy farm near Placerville. Louis was the son of a plantation owner father and an enslaved mother who fled to California. Sylvia and Louis Stark had seven children: Emily Arabella “Emma” (1857–1890), who became the first Black Canadian teacher on Vancouver Island; Willis Otis (1858–1943); John Edmond (1860–1930); Abraham Lincoln (1863–1908); Hannah Serena (1866–88); Marie Albertina (1867–1966), who wrote a family history; and Louisa (1878–1971).

Emigration to British Columbia

During the 1850s, the state of California passed a series of discriminatory laws. The United States Supreme Court ruled in the Dred Scott decision of 1857 that Black Americans, both free and enslaved, were not citizens under the American Constitution.

James Douglas, then governor of Vancouver Island (later governor of British Columbia), invited Black Americans to settle there, sending messages of welcome to community leaders in California. Douglas’s mother, Martha Ann Ritchie, had been born a “free woman of colour” in Barbados. He promised that Black American immigrants to Vancouver Island would receive British citizenship and the opportunity to purchase land. Douglas was alarmed by the influx of American miners (see Fraser River Gold Rush) and the threat of annexation to the United States. He thought that Black Americans would be more sympathetic to British rule. The Estes and Stark families were among the more than 600 Black Americans who emigrated to British Columbia from California in 1858–59.

Salt Spring Island

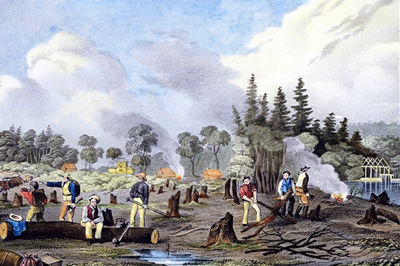

Sylvia Stark’s parents bought farmland in Saanich near Victoria. However, Sylvia and Louis Stark and their children thought that land prices on Vancouver Island were too expensive and decided to join the first group of settlers on Salt Spring Island in 1860. Of the 20 families who settled there in 1860, nine were Black American.

The Stark family settled at Vesuvius Bay. Their first home was a log cabin with a quilt over the door frame. Bears and cougars lived on the island. The presence of the settlers was resented by the Haida and Cowichan peoples, who often visited the island. In these difficult conditions, Sylvia Stark found solace in her Methodist faith. She later told her daughter Marie Albertina, “Now I can see the hand of God guiding me through all of troubles.”

By 1861, the Starks farm was prospering. A visiting Methodist minister, Ebenezer Robson, wrote that “Mr. Stark has about 30 head of cattle. He sowed one quart of wheat near his home last winter and reaped 180 quarts in the summer. His wife…filled my sacks with good things, 4 pounds fine fresh butter, 2-quart bottles new milk.” In 1868, the Starks moved their farm to Fruitvale on Salt Spring Island.

Sylvia Stark was one of more than 600 Black Americans who emigrated to British Columbia in 1858. She was one of the original settlers on Salt Spring Island. Photo taken at the home of Naidine Sims in the 1940s.

(courtesy Salt Spring Island

Archives/Estes-Stark

Collection/989024037)

Later Life

In 1874, the Starks and their four younger children moved to Cedar in Nanaimo’s Cranberry district on Vancouver Island. They left their eldest son, Willis, to manage the farm on Salt Spring Island. The move allowed Louis Stark to spend part of the year prospecting for gold and other minerals. However, Sylvia was unhappy in Cedar. In 1885, she separated from her husband and returned to Salt Spring Island with her children (except Louisa, who remained with her father).

Louis Stark died in mysterious circumstances in 1895. His family suspected that he had been murdered in a dispute over mineral rights to a coal seam on his Nanaimo farm. Sylvia spent the rest of her life on Salt Spring Island, running the farm in Fruitvale with her son Willis until his death in 1943. She died in 1944 at the age of 105.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

.jpg)