The Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS) was established on 31 July 1942 during the Second World War. It was the naval counterpart to the Canadian Women’s Army Corps and the Royal Canadian Air Force Women’s Division, which had preceded it in 1941. The WRCNS was established as a separate service from the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN). It was disbanded on 31 August 1946. Today, women are fully integrated into the navy. As of December 2024, more than 20 per cent of Canadian naval personnel were women.

Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service: Key Facts

| Founded on 31 July 1942 |

| Disbanded on 31 August 1946 |

| 6,783 women served in the WRCNS |

| 11 died on active service (from sickness or accidents) |

| Personnel served in Canada, Newfoundland (then a separate Dominion), the United States and Great Britain |

| “Wrens” served in 39 trades, including administrative and clerical work, signalling, coding, and wireless telegraphy |

Origins

When Canada entered the Second World War in September 1939, thousands of Canadian men volunteered for service. However, recruitment failed to keep pace with increasing demands. In April 1941, representatives from the Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Navy and RCAF met in Ottawa to discuss the possibility of women entering the service in non-combat and non-medical roles. Although they initially decided against this idea, the air force soon changed its mind. In July, the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (CWAAF) was established; it was later renamed the RCAF Women’s Division. The Canadian Women’s Army Corps was created in August.

The navy was the last service to create a women’s auxiliary. The Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS) was founded in July 1942. It was patterned on the British Women’s Royal Navy Service (WRNS). The term “Wrens,” by which WRCNS members were known, was the logical slurring of the British WRNS. Indeed, with no existing Canadian naval model, the WRCNS closely followed the British example, with initial senior leadership positions filled by British Wrens on loan. Three WRNS members arrived in Canada in May 1942 to develop the nucleus of the new organization. WRNS Chief Officer Dorothy Isherwood was the first director of the WRCNS, serving in that position until September 1943.

Training

In September, an initial cadre of 67 Canadian women underwent a probationary course at Kingsmill House, Ottawa. Soon after, the basic training centre HMCS Conestoga was established at Galt, Ontario, in — to the reported amusement of the women — a vacant girls’ reformatory school, with the first class starting in October 1942. Unlike male sailors, who were recruited into the Royal Canadian Navy as either officers or (non-commissioned) ratings, all but a very few Wrens began their service in the non-commissioned ranks, and as such passed through Conestoga. Some women were selected to become officers and underwent further training at Hardy House, in Ottawa. The first of an eventual 21 classes was held in February 1943.

Leadership

In June 1943, Lieutenant-Commander Isabel Macneill, one of the graduates of the first course, was appointed commanding officer of Conestoga. She was the first female to command an HMC “Ship.” (In naval terms, a commissioned shore establishment with the HMCS designation is referred to as a “stone frigate.”)

On 18 September 1943, Commander (later Captain) Adelaide Sinclair became the first Canadian director of the WRCNS, an appointment she held until the service was disbanded. Formerly a lecturer in political science at the University of Toronto, Sinclair went on after the war to prominent positions in public service. From 1957 until retirement in 1967 she was deputy executive director of the United Nations Children's Fund (Unicef).

Operations

The navy had lagged in the creation of a women’s division due in part to a certain narrow-mindedness. Another important factor was that the navy grew at a slower rate than the other services because of long lead times for shipbuilding. Demands for manpower were therefore slower in the navy than the army and air force. Full mobilization of the WRCNS in turn was delayed by initial problems of recruiting. This was resolved after December 1942 by integrating the recruitment of women with that of males and by building suitable new accommodation in major naval population centres.

By 31 August 1945, 6,783 women had enlisted overall in the WRCNS. At its peak, the organization had 5,893 members, more than 1,000 of whom served outside Canada. None were killed in action, but 11 died on duty, due to illness or accidents.

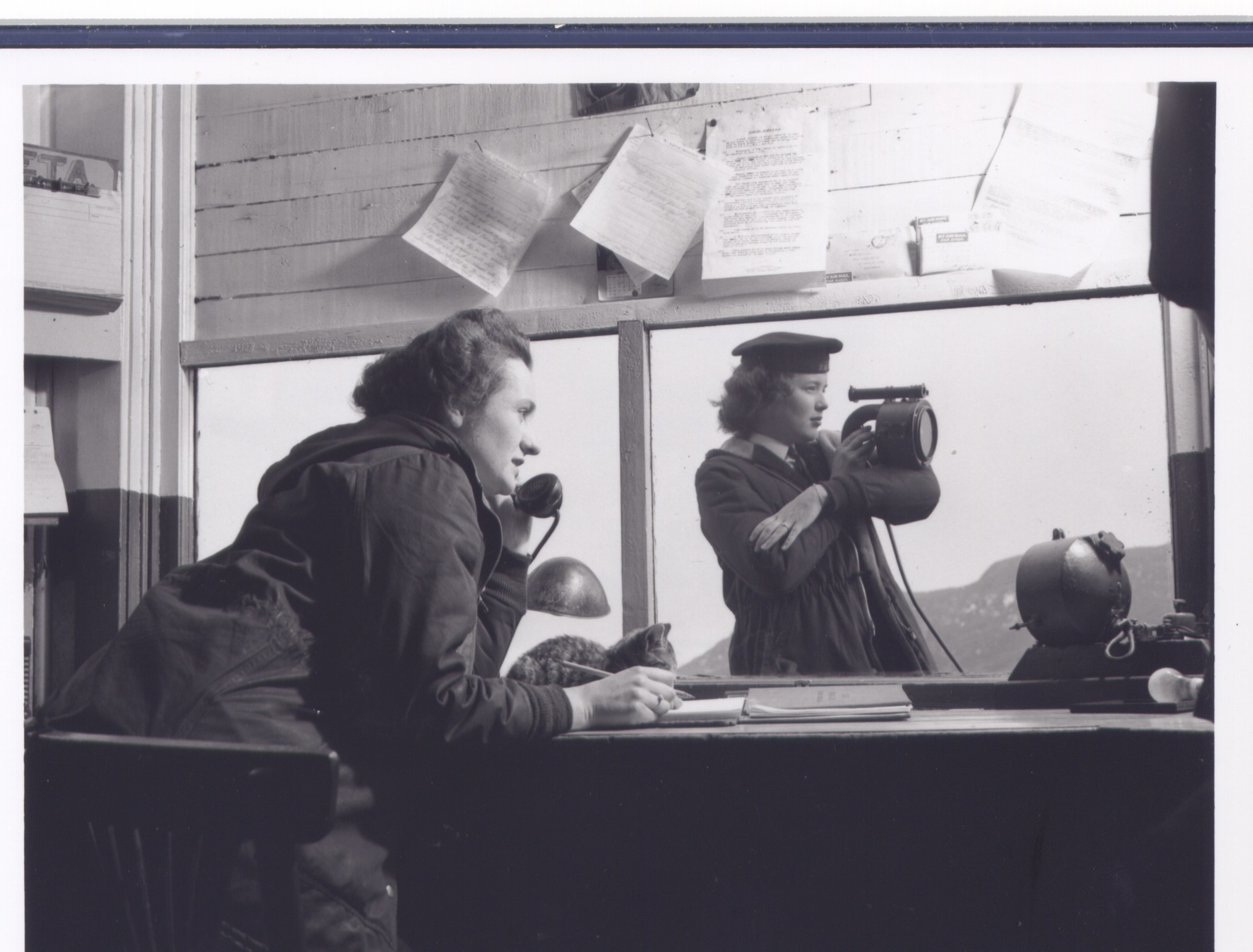

The women filled some 39 different trades. Wrens in Canada served primarily in administrative positions at the naval bases in Halifax and Esquimalt and associated naval training establishments, and at Naval Service Headquarters in Ottawa. They are probably remembered best for staffing the operational map plots in command headquarters, and for taking on the bulk of duties at the various naval signals intelligence sites on both coasts.

More than 500 Wrens were stationed at the Canadian naval base HMCS Avalon in St. John’s, Newfoundland (then a separate Dominion). Another 500 were stationed at the shore establishment HMCS Niobe in Great Britain (mostly in London, Plymouth and Londonderry), and some 50 at naval offices in Washington DC, and New York City.

Did you know?

Beatrice Worsley, the first female computer scientist in Canada, was one of thousands of Wrens who served in the Second World War. After earning her undergraduate degree in mathematics and physics, Worsley joined the WRCNS as a probationary sub-lieutenant at HMCS Conestoga. She was soon commissioned and transferred to the Naval Research Establishment (NRE) at HMCS Stadacona in Halifax, where she worked as a harbour defense researcher. This included data analysis related to degaussing ships, a process that reduced the ships’ magnetic signature to make them safer around German magnetic mines. Worsley remained at the NRE until 1946, when she began a master’s degree in mathematics and physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Primary Sources: Interviews from The Memory Project Archive

In 2009, The Historica-Dominion Institute (now Historica Canada) began sending interviewers across Canada to record Second World War testimonials and artefacts. The Memory Project Archive, now part of The Canadian Encyclopedia, includes many interviews with veterans of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service: Dorothy Butler, Margaret O’Connor, Carol Elizabeth Duffus, Ruth Werbin, Margarita “Madge” Trull (née Janes), Mary Kearney, Eileen Cole, Catharine “Kay” Stevens, Margaret Haliburton, Ruth McMillan, Wilma Fern Stanley, Una May Miklos, Rae Grey, Beatrice Mary Geary (née Shreiber), Sheila Elizabeth Whitton, Olive Henderson, Ella Thomson, Joan Thompson Voller, Donna Pauline Robertson, Jean Ida MacDonald, Janet Hester Watt, Jean Adams, Enid Anne Liddell, Lydia Rose Daikens, Norma Graham McArthur, Marie Duchesnay, Ruby Somers, Mary Owen, and Vicki La Prairie. The archive also includes interviews with veterans of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (UK) who later moved to Canada.

Legacy

A women’s division was re-constituted in 1951 during the Korean War as part of a re-organized Royal Canadian Navy (Reserve). In 1955, a women’s component of the regular navy was authorized, but no longer as a separate service. The name Wrens remained popular with female sailors, however, and continued in use after disbandment of the Royal Canadian Navy with unification of the armed forces in 1968. The name was particularly popular in the naval reserve, which maintained a higher proportion of serving women than the regular force.

Today, women are fully integrated into the navy, including in combat roles, and the term Wrens has fallen into disuse other than for sentimental, nostalgic associations. As of December 2024, more than 20 per cent of Canadian naval personnel were women — 22 per cent of officers and 20 per cent of non-commissioned members (NCMs). In total, women comprise approximately 16.6 per cent of the Canadian Armed Forces (regular force and primary reserve): 19.9 per cent of officers and 15.5 per cent of NCMs. (See also Canadian Women in the Cold War Navy; Women in the Canadian Armed Forces; Women and War.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom