Most adult Canadians earn their living in the form of wages and salaries and are therefore associated with the definition of "working class." Less than a third of employed Canadians typically belong to unions. Unionized or not, the struggles and triumphs of Canadian workers are an essential part of the country's development.

19th Century

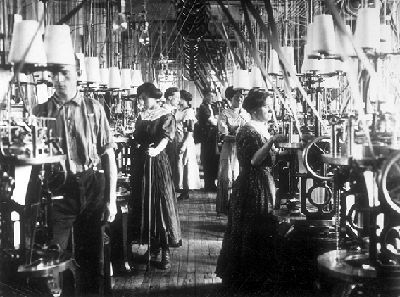

The working class emerged during the 19th century in English Canada as a result of the spread of industrial capitalism in British North America. At the time, it was common for many Canadians to support themselves as independent farmers, fishermen and craftsmen. Entire families contributed to the production of goods (see History of Childhood). However, the growing differentiation between rich and poor in the countryside, the expansion of resource industries (see resource use), the construction of canals and railways, the growth of cities and the rise of manufacturing all helped create a new kind of workforce in which the relationship between employer and employee was governed by a capitalist labour market and where women and children no longer participated to as great an extent.

Company towns, based on the production of a single resource such as coal, emerged during the colonial period and provided a reserve of skilled labour for the company and a certain degree of stability for the workers. When violence erupted, the companies' responses varied from closing the company-owned store to calling in the militia. Domestic service (servants, housekeepers, etc.) emerged as the primary paid employment for women.

Meanwhile, child labour reached its peak in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, supplemented by immigrant children brought from Britain by various children's aid societies. The workers were often cruelly exploited. For any worker, job security and assistance in the event of illness, injury or death were almost non-existent.

For most of the 19th century, unions were usually small, local organizations. Often they were illegal. In 1816 the Nova Scotia government prohibited workers from bargaining for better hours or wages and issued prison terms as a penalty. Nevertheless, workers protested their conditions, with or without unions, and sometimes violently. Huge, violent strikes took place on the Welland and Lachine canals in the 1840s. Despite an atmosphere of hostility, by the end of the 1850s local unions had become established in many Canadian centers — representing workers of all linguistic backgrounds, including francophone minorities in English Canada — particularly skilled workers such as printers, shoemakers, moulders, tailors, coopers, bakers and other tradesmen.

Rise of Unions

The labour movement gained cohesiveness when unions created local assemblies and forged ties with British and American unions in their trade. In 1872 workers in Ontario industrial towns and in Montréal rallied behind the Nine-Hour Movement, which sought to reduce the working day from up to 12 hours to nine hours. Hamilton's James Ryan, Toronto's John Hewitt and Montréal's James Black led the workers. Toronto printers struck against employer George Brown; in Hamilton on 15 May 1872, 1,500 workers paraded through the streets.

The ambitiously titled Canadian Labor Union, formed in 1873, spoke for unions mainly in southern Ontario. It was succeeded in 1883 by the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada (TLC), which became a lasting forum for Canadian labour. In Nova Scotia the Provincial Workmen's Association (1879) emerged as the voice of the coal miners and later spoke for other Maritime workers.

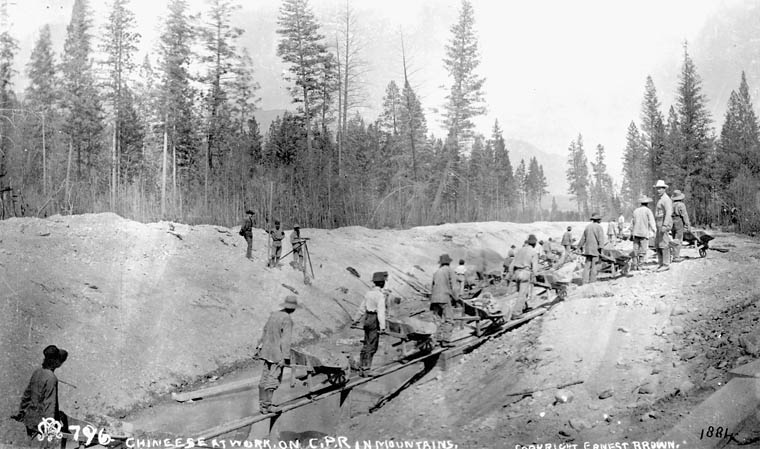

The most important organization of this era was the Knights of Labor, which organized more than 450 assemblies with more than 20,000 members across the country. The Knights were an Industrial Union, which brought together workers regardless of craft, race (excepting Chinese) or sex. Strongest in Ontario, Québec and British Columbia, the Knights were firm believers in economic and social democracy, and were often critical of the developing industrial, capitalist society. Key Knights included A.W. Wright, Thomas Phillips Thompson and Daniel J. O'Donoghue.

By the late 19th century the "labour question" had gained recognition. The Toronto printers' strike of 1872 led Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald to introduce the Trade Unions Act, which stated that unions were not to be regarded as illegal conspiracies. The Royal Commission on the Relations of Labour and Capital, which reported in 1889, documented the sweeping impact of industrialization in Canada, and the commissioners strongly defended unions as a suitable form of organization for workers. Another sign of recognition came in 1894 when the federal government officially adopted Labour Day as a national holiday falling on the first Monday in September.

Working Class Grows

The consolidation of Canadian capitalism in the early 20th century accelerated the growth of the working class. From the countryside, and from Britain and Europe, hundreds of thousands of people moved to Canada's booming cities and tramped through Canada's industrial frontiers (see bunkhouse men). Most workers remained poor, their lives dominated by a struggle for the economic security of food, clothing and shelter. By the 1920s most workers were in no better financial position than their counterparts had been a generation earlier.

Not surprisingly, most strikes of this time concerned wages, but workers also went on strike to protest working conditions, unpopular supervisors and new rules, and to defend workers who were being fired. Skilled workers were particularly alarmed that new machinery and new ideas of management were depriving them of some traditional forms of workplace authority.

Union Divisions

Despite growing membership, divisions appeared between unions, and this limited their effectiveness. The most aggressive organizers were the craft unions, whose membership was generally restricted to the more skilled workers. Industrial unions were less common, though some, such as the United Mine Workers, were important. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) unified American craft unions and, under Canadian organizer John Flett, chartered more than 700 locals in Canada between 1898 and 1902; most were affiliated with the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada (TLC). At the TLC meetings in 1902 the AFL craft unions voted to expel any Canadian unions, including the Knights of Labor, in jurisdictional conflict with the American unions, a step that deepened union divisions in Canada.

Department of Labour

The attitudes of government were also a source of weakness. Though unions were legal, they had few rights under the law. Employers could fire union members at will, and there was no law requiring employers to recognize a union chosen by their workers. In strikes employers could ask governments to call out the troops and militia in the name of law and order, as happened on more than 30 occasions before 1914 (see Fort William Freight Handlers Strike).

With the creation of the Department of Labour in 1900, the federal government became increasingly involved in dispute settlement. The Industrial Disputes Investigation Act (1907), the brainchild of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King,required that some important groups of workers, including miners, must go through a period of conciliation before they could engage in "legal" strikes. Since employers were still free to ignore the unions, dismiss employees, bring in strikebreakers and call for military aid, unions came to oppose this legislation.

Activism

One of the most important developments in the pre-war labour movement was the rise of Revolutionary Industrial Unionism, an international movement that favoured the unification of all workers into one labour body to overthrow the capitalist system and place workers in control of political and economic life. The Industrial Workers of the World,founded in Chicago in 1905, rapidly gained support among workers in western Canada such as fishermen, loggers and railway workers. The group, also known as "Wobblies", attracted nationwide attention in 1912 when 7,000 ill-treated immigrant railway workers in the Fraser Canyon struck against the Canadian Northern Railway. A number of factors, including government suppression, hastened its demise during the war.

The First World War had an important influence on the labour movement. While workers bore the weight of the war effort at home and paid a bloody price on the battlefield, many employers prospered. Labour was excluded from wartime planning and protested against conscription and other wartime measures. Many workers joined unions for the first time and union membership grew rapidly, reaching 378,000 in 1919. At the end of the war, strike activity increased across the country. There were more than 400 strikes in 1919, most of them in Ontario and Québec.

Three general strikes also took place that year, in Amherst, Toronto and Winnipeg. In Winnipeg the arrest of the strike leaders and the violent defeat of the strike demonstrated that in a labour conflict of this magnitude the government would not remain neutral (see Winnipeg General Strike). In 1919 as well, the radical One Big Union (OBU) was founded in Calgary. It soon claimed 50,000 members in the forestry, mining, transportation and construction industries.

Despite the formation of the OBU and the Communist Party of Canada, the 1920s remained a period of retreat for organized labour. The exception was the coal miners and steelworkers of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, who led by J.B. McLachlan, rebelled repeatedly against one of the country's largest corporations (see Cape Breton Strikes, 1920s’s).

Great Depression

The 1930s marked an important turning point for workers. The biggest problem of the decade was unemployment. In the depths of the Great Depression more than one million Canadians were out of work. Emergency relief was inadequate and was often provided under humiliating conditions (see Unemployment Relief Camps). Unemployed workers'associations fought evictions and gathered support for Employment Insurance, a reform finally achieved in 1940.

One dramatic protest was the On To Ottawa Trek of 1935, led by former Wobbly Arthur "Slim" Evans,an organizer for the National Unemployed Workers' Association. The Depression demonstrated the need for workers' organizations, and by 1949 union membership exceeded one million workers. Much of the growth in union organization came in the new mass-production industries: rubber, electrical, steel, auto and packing house workers.

The communist-supported Workers Unity League (1929-36) had pioneered industrial unionism in many of these industries. The Oshawa Strike (8-23 August 1937), when 40,000 workers struck against General Motors, was among the most significant in establishing the new industrial unionism in Canada. Linked to the Congress of Industrial Organizations in the US, many of the new unions were expelled by the TLC and formed the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) in1940.

Second World War

Early in the Second World War the federal government attempted to limit the power of unions through wage controls and restrictions on the right to strike (see Wartime Prices and Trade Board; National War Labour Board), but many workers refused to wait until the war was over to win better wages and union recognition. Strikes such as that of the Kirkland Lake gold miners in 1941 persuaded the government to change its policies. In January 1944 an emergency order-in-council protected the workers' right to join a union and required employers to recognize unions chosen by their employees. This long-awaited reform became the cornerstone of Canadian industrial relations after the war, in the Industrial Relations and Disputes Investigation Act (1948) and in provincial legislation.

At the end of the war a wave of strikes swept across the country. Workers achieved major improvements in wages and hours, and many contracts incorporated grievance procedures and innovations such as vacation pay. Some industry-wide strikes attempted to challenge regional disparities in wages. The Ford strike in Windsor, between 12 September and 29 December 1945, began when 17,000 workers walked off the job. The lengthy, bitter strike resulted in the landmark decision by Justice Ivan C. Rand,which granted a compulsory check-off of union dues (see Rand Formula; Windsor Strike). The check-off helped give unions financial security, though some critics worried unions might become more bureaucratic as a result.

By the end of the war Canadian workers had become more active politically. The labour movement had become involved in politics after 1872 when the first working man (Hamilton's Henry Buckingham Witton) was elected to Parliament as a Conservative candidate, as was A.T. Lépine, a Montréal leader of the Knights of Labor in 1888. In 1874, Ottawa printer D.J. O'Donoghue was elected to the Ontario legislature as an independent labour candidate. Labour candidates and workers' parties were often backed by local unions. In 1900 A.W. Puttee, a Labour Party founder, and Ralph Smith,the TLC president, were elected to Parliament. The Socialist Party of Canada appealed to the radical element and elected members in Alberta and BC.

The new rights of labour and the rise of the Welfare State were the decisive achievements of the 1930s and 1940s, promising to protect Canadian working people against major economic misfortunes. The position of labour in Canadian society was strengthened by the formation of the Canadian Labour Congress (1956), which united the AFL and the Canadian Congress of Labour,and absorbed the OBU. The CLC was active in the founding of the New Democratic Party. Despite the emergence of rival union centrals such as the Confederation of Canadian Unions (1975) and the Canadian Federation of Labour (1982), as of 2012 the CLC continued to represent 31 per cent of all Canadian employees.

Public Sector

Steady growth in government employment during this period meant by the 1970s one in five workers was a public employee. With the exception of Saskatchewan, which gave provincial employees union rights in 1944, it was not until the mid-1960s, following an illegal national strike by postal workers (see postal strikes), that public employees gained collective bargaining rights similar to those of other workers. In 1996, three of the six largest unions in Canada were public-service unions, whose growth has increased the prominence of Canadian over American-based unions in Canada. Several major industrial unions, including the Canadian Auto Workers, reinforced this trend by separating from their American parent unions.

Another significant change has been the rise in the number of female workers. By 2012, females 15 years and older made up more than 62 per cent of the labour force, while more than 32 per cent worked in unionized jobs. The change was reflected in the growing prominence of women union leaders and in concern over issues such as maternity leave, child care, sexual harassment and equal pay to women workers for work of equal value.

Despite the achievements of organized labour, the sources of conflict between employers and employees have persisted. Determined employers have been able to resist unions by using strikebreakers and by refusing to reach agreement on first contracts. Workers have continued to exert little direct influence over the investment decisions that govern the distribution of economic activity across the country. In collective agreements, issues such as health, safety and technological change have received greater attention. But the employer's right to manage property has predominated over the workers' right to control the conditions and purposes of their work.

Government Intervention

Governments have often acted to restrict union rights. On occasion, as in the 1959 Newfoundland Loggers' Strike, individual unions have been outlawed. Since the 1960s and 1970s, governments have turned with increasing frequency to the use of legislated settlements, especially in disputes with their own employees. In 2013, Canada’s public service unions were in heated debate with the Conservative government regarding federal legislation that proposed sweeping changes to labour laws and collective bargaining. If passed, Bill C-4 would put public sector employees on similar footing, in terms of rights and protections, as private sector workers. It would also give government the exclusive right to determine essential services and would limit the use of arbitration in settling disputes.

Despite the existence of the welfare state, many workers have continued to suffer economic insecurity and poverty. The labour market has also failed to provide full employment for Canadian workers. Since the 1980s more than one million Canadians are regularly reported unemployed. Today, most working people feel threatened by pressures arising from the globalization of the economy and new employer strategies to reduce labour costs. The global recession, which began to affect Canada in 2008, has also lead to changes in job security, employment opportunities and the administration of employment insurance benefits.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom