Background and Administration

A committee of business leaders, chaired by C.M. Drury, was originally instrumental in convincing John Diefenbaker, then prime minister, that Canada's 100th anniversary should be a memorable occasion. Planning for the country’s centennial celebrations officially began with the formation of the Centennial Commission in January 1963. One of the country's best-known publicists, John Fisher (who was dubbed “Mr. Canada”), was appointed Centennial commissioner. Fisher’s tenure continued under Prime Minister Lester Pearson, and he was assisted by associate commissioners Georges E. Gauthier and Gilles Bergeron.

Overview

A wide variety of events and activities were held during the year, with a special focus on 1 July. Celebrations were held throughout the country, ranging across all fields of endeavour and mobilizing all facets of Canadian society to an unprecedented degree, from the creative and performing arts to sports, businesses, cultural organizations and schools. In a lighter vein, there were bathtub races, parades and period costume parties. The town of St. Paul, Alberta, even built a landing pad for UFOs.

The year’s commemorations fell into two categories: monuments and activities. In a desire to leave behind a literally concrete memory of the year, the federal and provincial governments financed a wide variety of building projects. The federal Centennial Commission set aside $25 million, roughly $1 for every person in Canada. Each dollar that was spent on a centennial event by a municipality was matched by $1 from the federal government and $1 from the respective provincial government.

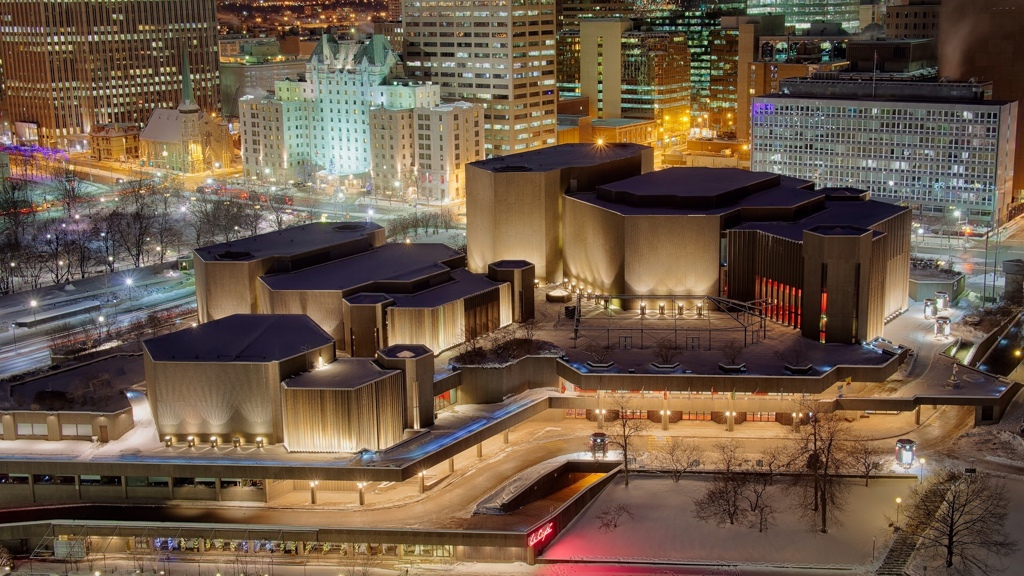

Such largesse encouraged the construction of facilities such as libraries, art galleries, theatres and sports complexes. Each province acquired a centennial memorial building. The most lavish concrete monument was the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, paid for entirely by the federal government. The largest and most renowned, expensive and all-encompassing special event was Expo 67 and its companion World Festival, both in Montréal.

Opening Celebrations

The festivities were launched at midnight on 31 December 1966, when Prime Minister Lester Pearson, Secretary of State Judy LaMarsh (the minister responsible for the Centennial Commission), Opposition Leader John Diefenbaker and thousands of others participated in a ceremony on Parliament Hill that culminated in the lighting of the gas-powered Centennial Flame. Cities and towns across the country also held fireworks, parades, bell-ringing and lighting ceremonies. In Toronto, a torchlight parade and fireworks at Queen’s Park drew a crowd of about 40,000.

Centennial Logo

Centennial publications and events were all branded with the Centennial logo, designed by Stuart Ash. It consisted of a stylized maple leaf composed of 11 equilateral triangles representing Canada’s 10 provinces and the Northwest Territories (Canada’s accepted geography at the time).

Centennial Medal

A special Centennial Medal was instituted on 1 July 1967 to recognize individuals who had made a valuable contribution to the country. Designed by Bruce W. Beatty, the Centennial Medal is a circular silver medal hung from a red-and-white-striped ribbon. One side of the medal bears the Royal Cipher and Crown superimposed over a maple leaf, with the words CONFEDERATION CANADA CONFÉDÉRATION inscribed along the circumference. The reverse side features Canada’s coat of arms with the dates 1867–1967 inscribed underneath.

Members of the Canadian Armed Forces received about 30 per cent of the 29,500 medals that were issued. Nominations were submitted by federal, provincial and municipal governments, as well as cultural, professional and educational organizations, veterans’ groups, sports associations and charitable organizations.

Centennial Coins

In 1967, a special coinage was issued commemorating the centenary of Confederation. The Minister of Finance held a competition for the design of a motif on one side of each denomination, each of which bore the bust of the Queen on the opposite side. The winning entrant for all denominations was artist Alexander Colville. The penny featured a dove in flight; the five-cent piece a rabbit; the 10-cent piece a mackerel; the 25-cent piece a bobcat; the 50-cent piece a howling wolf; and the dollar a Canada goose in flight.

Confederation Train

Of special note was the Confederation Train, a diesel locomotive and specially designed coach cars loaned by the Canadian National Railway, which were filled with exhibits showcasing Canadian history and culture. Emblazoned with the Centennial logo on the nose of the engine and graphic lettering spelling out CANADA 1867 1967 in purple and white along the cars, the Centennial Train began its journey in Victoria, British Columbia, on 9 January 1967. It awed 2.5 million visitors in 63 cities across the country, its horn sounding out the first four notes of “O Canada” whenever it arrived and departed. It arrived in Nova Scotia in October and made its final stop in Montréal on 5 December.

Centennial Caravan tractor-trailers, carrying similar exhibits, reached 6.5 million people in 655 smaller communities that the train did not reach. The train and caravans were both very popular attractions.

Canadian Armed Forces Tattoo

Canada’s armed forces contributed to Centennial celebrations with the travelling Canadian Armed Forces Tattoo 1967. The largest peacetime event in Canadian military history to that time, it comprised 1,700 military personnel from all three branches of the armed forces re-enacting more than 300 years of Canada’s military history in popular shows across the country.

RCAF and RCMP Events

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) restored two Avro 504K planes, Canada’s first military aircraft, and flew them at air shows across the country along with an acrobatic flying team called the Golden Centennaires, the predecessors of the Snowbirds. June 1967 saw National Veterans Week activities as well. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Musical Ride and RCMP Band also toured the country, including the band’s first visit to the Canadian Arctic.

Centennial Babies

Babies born on 1 July 1967 were declared “Centennial Babies.” Various communities also declared the first baby born there after the Centennial to be the Centennial Baby of that region. Kara ffolliott (née Kara Marie Ott) was the first child born in Canada on 1 July 1967 (at 12:18 a.m. in Regina, Saskatchewan) and was officially declared Canada’s Centennial Baby. Other Centennial Babies include model and television star Pamela Anderson (born at 4:08 a.m. in Ladysmith, British Columbia).

Cartier Typeface

Influential designer and typographer Carl Dair spent 10 years creating Canada’s first typeface for Roman letters. Named after explorer Jacques Cartier and dedicated to the Canadian people, it was commissioned by the federal government and released in January 1967. The typeface was used for the printing of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982. It was later adapted into the more popular Raleigh font, and in the late 1990s was redesigned as the digital font Cartier Book.

Performing Arts

The arts were a particular focus of the Centennial Commission. Under the Festival Canada umbrella, national tours were organized for Anne of Green Gables, Les Feux-Follets, Don Messer and His Islanders, the Montréal Symphony Orchestra, the National Ballet of Canada, the National Youth Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Gordon Lightfoot, and Ian and Sylvia Tyson.

A year-long festival was held in Ottawa, featuring performances by the above artists, the Canadian Opera Company and the Canadian Centennial Choir, which was formed specifically for the festivities. Performing arts groups across Canada received financial assistance for productions and commissions; the Canadian Music Centre alone received a grant of $60,000, which it used to commission some 45 works to be performed in Canada during 1967.

The Canadian Folk Arts Council (Conseil canadien des arts populaires) presented 100 folk festivals across Canada over the course of the year. Many music and dance groups were among the 35,000 participating in provincial and regional festivals that demonstrated Canada’s varied cultural heritage.

Music

Music performances were a major part of the Centennial celebrations (see Music at Expo 67). Across the country, professional and amateur entertainments were organized through grants to local groups. Countless choral groups, opera companies, orchestras, chamber ensembles, and popular and folk musicians gave special performances.

For classical music, the special funding enabled presentations of major works such as Britten's War Requiem by the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, Verdi's Requiem by the Victoria Symphony Orchestra, Orff's Carmina Burana by the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, Messiaen's Turangalîla-Symphonie by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, and Verdi's Otello and Gounod's Faust by the Montréal Symphony Orchestra. Operas premiered or presented included Harry Somers'Louis Riel and Raymond Pannell's The Luck of Ginger Coffey (the Canadian Opera Company), Rigoletto (Vancouver Opera) and Faust (Edmonton Opera Association).

Centennial Commission grants funded music competitions under the Federation of Canadian Music Festivals and Jeunesses Musicales Canada. Numerous Canadian composers received commissions from various organizations to compose music for the year’s celebrations, including: Louis Applebaum, Violet Archer, John Beckwith, Alexander Brott, Robert Fleming, Ann Southam and R. Murray Schafer, among others.

Of the numerous compositions written for Centennial Year, the one that achieved the greatest popularity and longevity was Gordon Lightfoot’s iconic “Canadian Railroad Trilogy,” commissioned by the CBC. Another very popular national song heard everywhere in Centennial Year was Bobby Gimby’s “Ca-na-da.” Dolores Claman’s and Richard Morris’s catchy “A Place to Stand (Ontari-ari-ari-o),” featured in the Academy Award-winning film of the same name, was also immensely popular in Ontario.

There was also an official “Centennial Hymn”/“Hymne de centenaire,” composed by Rex LeLacheur to English lyrics by Rev Kenneth Moyer and French lyrics by Ronald Duprès. Healey Willan's “Anthem for the Centennial of Canadian Confederation”/“Hymne à l'occasion du Centenaire de la Confédération canadienne,” known also as the “Centennial Anthem,” was set to lyrics by Robert Choquette (adapted into English by John Glassco). Another national song composed for Centennial Year was Raymond Gould and Frederick Sheffield's “My Canada.”

As a joint centennial project, RCA Victor and the CBC released the 17-album series Music and Musicians of Canada/Musique et musiciens du Canada, containing 42 compositions by 32 Canadians, performed by Canadian musicians; and the nine-album series Canadian Folk Songs: A Centennial Collection/Chansons folkloriques du Canada: Collection du Centenaire, containing 120 tracks.

Literature

To encourage Canadian literature, the Centennial Commission awarded grants to Canadian authors to write books on Canadian topics (see Centennial Literature). The federal government also presented 451 libraries with a total of 23,000 books to promote Canadian culture.

Film and Broadcasting

The National Film Board created its Challenge for Change (Societé Nouvelle) program to address social issues of the day through the medium of film and video. It also created the innovative film Helicopter Canada (1966), an hour-long aerial portrait of the country, and the multi-screen installation film Labyrinth (1967), which proved to be one of the most popular attractions at Expo 67. Presented in a five-storey concrete edifice, the project served as an early template for the IMAX projection system.

A Place to Stand (1967), commissioned by the Ontario government for the Ontario pavilion at Expo 67, also served as a precursor to the IMAX process. An 18-minute film comprised of about 90 minutes of footage edited across as many as 15 different panels simultaneously, the $500,000 film used its innovative “multi-dynamic image technique” to paint a promotional picture of the province’s people, places and industries. It went on to win the Canadian Film Award for Film of the Year and the Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film.

Visual Arts

The Bank of Montreal got involved by sponsoring an artist to sketch contemporary Canadian scenes from coast to coast. The National Gallery of Canada undertook a display of 350 works of Canadian art covering 300 years, the largest exhibition of Canadian art to that time.

Sports

Sport celebrations in 1967 equalled those of the arts across the country. The first Canada Winter Games were held in Québec City that year, and the Canadian Paralympic Games took place in June. More than 100 national and international sports competitions were held in Canada in 1967, ranging from mainstream events like the Pan-Am Games in Winnipeg, to snowshoeing contests and lacrosse tournaments.

School children were not forgotten. The 1967 Centennial Athletic Awards Program tested children’s fitness. Students were awarded cloth badges at gold, silver, bronze and participation (red) levels.

Canoeing, that stereotypically Canadian activity, was also a highlight of the year. Events ranged from individuals traversing the waterways to the Centennial Voyageur Canoe Pageant, a race that involved 100 paddlers canoeing in teams from the Rocky Mountains to Montréal.

Community Festivals and Programs

Other sizable and significant events included the inaugural Caribana in Toronto (now the Toronto Caribbean Carnival), established by the Caribbean community to mark the contributions of Canadians of West Indian origin, as well as a Centennial Folk Festival and Highland Games in Halifax in August.

A nationally funded youth travel program encouraged unity and cultural exchanges by enabling 12,000 high-school students to visit areas of Canada far away from their homes.

Closing Celebrations

The year ended, as it had begun, on Parliament Hill. The Centennial Flame was originally to have been extinguished; instead, it was left alight by popular consent. It was to become a symbol for a year that was not merely significant in and of itself, but one that marked the emergence of Canada as a mature and self-confident nation.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom