Anything involving animals that creates public interest and publicity, no matter how briefly it maintains that interest, may be considered an animal issue. The close relationship between humans and animals has persisted since prehistoric times but only since the late 1800s have societies for the protection of animals have been in existence in the Western world.

During the Victorian era, the antivivisection movement developed to oppose science's use of animals in biomedical research. The battle between vivisectionists and antivivisectionists resulted in the UK's Cruelty to Animals Act (1876). This legislation heralded a clear victory for the antivivisection movement and imposed upon Britain's medical scientists a system of licensing, inspection and bureaucratic practices. The need for the act has been debated ever since and in 1986 was strengthened and replaced by the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act.

After World War II biomedical research escalated tremendously. New drugs, treatments and techniques were discovered at a pace that permitted the health sciences to prevent and treat conditions previously thought to be incurable, to prolong life and relieve suffering. In Canada since 1968, surveillance of the ethical use of the 2 million experimental animals used annually in biomedical research has been the responsibility of the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC). CCAC pioneered the requirement of local institutional animal-care committees, a concept later adopted worldwide. Local animal-care committees ensure that CCAC guidelines and directives are adhered to.

The number of animals used in research has decreased because of the high cost in acquiring and housing animals. Also, with the development of transgenic animals - those that have had their genes altered to produce human disease states more closely - fewer are needed. Additionally, fewer animals are needed because of the development of alternative techniques, such as tissue culture and computer simulation. Although animal experiments have resulted in medical and surgical advances for humans and for animals themselves, criticism of the use of animals remains.

In 1975 clinical psychologist Richard Ryder coined the term "speciesism," which means a bias favouring one's own species. This bias has been criticized by philosophers who opposed the Judeo-Christian concept of mankind's "dominion" over animals and held that animals had rights similar to those of humans (such as living without suffering and use inflicted by the human animal).

The latter view is shared by the vegetarian and the vegan (those who avoid eating or using all animal products) movements. While the 2 movements have publicized their philosophies for many years, the number of adherents remained reasonably steady until heart and stroke societies embraced the decrease of animal fats in the diet as a possible preventive measure to decrease the acceleration of heart disease and stroke. Support for their philosophies has increased, but interestingly the decrease in meat in the diet is not related to a greater interest in the humane treatment and use of animals, but rather to an interest in a healthier lifestyle.

In the 1980s, Dr Peter Singer and James Mason in the US, and others, extended the discussion of animal liberation to include a "new ethics" for the treatment of animals. They widened their fields of concern to domesticated animals raised under new, intensive livestock-management practices; those in entertainment such as rodeos, circuses and zoos; and those hunted for sport or for their skins.

Now public interest and support for advocacy by animal-rights proponents seem to be waning. For example, the wearing of fur is not deplored but is generally accepted as an individual choice and right. The paint spraying of those wearing fur in public no longer occurs and sales of fur have increased in most countries. Public attitudes may be related to disagreement with the activism of the anti-fur movement or possibly to the significant changes made by trappers and the fur industry in the promotion of humane traps, codes of practice and trapper education. Canada, particularly the federally supported Fur Institute of Canada, championed the development and acceptance of international standards for humane traps, resulting in the establishment of such standards by the International Standards Organization. Part of the change in attitude may also be the acceptance of furs raised for the purpose under acceptable housing and husbandry practices and that those trapped in the wild represent a renewable natural resource.

Contemporary Issues

A number of animal issues continue to arouse ongoing public interest and concern.

Livestock-Management Practices

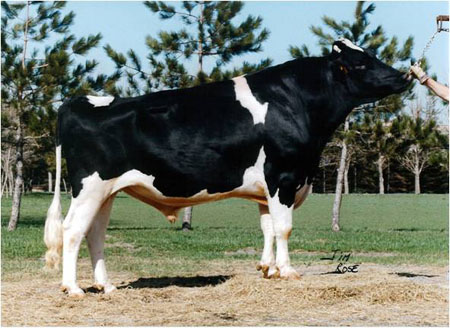

The livestock industry, in developing modern methods to produce a profit for the farmer and an economical product for the consumer, has developed some intensive livestock-management practices that are being questioned by those concerned about animal welfare (see Animal Agriculture). In order to tell their side of the story, there have been several livestock-producing groups whose primary purpose is to inform the public of their efforts to ensure that livestock and poultry are treated humanely on Canadian farms.

Agriculture Canada has published Codes of Practice for most species of animals and poultry raised on farms in Canada. These publications resulted from a consensus of animal scientists, veterinarians, farmers, regulators and animal-welfare representatives.

Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) are diseases that affect the central nervous system. They are always fatal. The animal issue that came to the forefront in 1996 - and has done more to raise the profile of animals in the food chain than any animal rights activity - was the occurrence of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) or mad cow disease. While the link between BSE and a similar human disease, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), has not been proven scientifically, suspicion that BSE might be capable of crossing into other species - specifically human beings - surfaced because of a disproportionate incidence of vCJD in Britain compared to other countries.

BSE was first reported in the UK in the mid-1980s. There have been few reported cases in Canada. Canada has banned the importation of live animals, frozen embryos and semen from any country reporting BSE.

It was first thought that the UK cattle became infected by eating feed supplements of sheep offal or sheep meat meal that were infected with scrapie, another TSE found in sheep and goats. Cross-species transfer (from sheep to cattle) of a TSE has been dismissed. Evidence suggests that the UK cattle became infected by eating cattle-based feed supplements. Cases of scrapie are reported in Canadian sheep each year. All the diseased sheep are killed and burned. Canada also has strict import regulations in the importation of live sheep. A disease in elk and deer in western Canada, known as chronic wasting disease, is also a TSE.

Foot and Mouth Disease

Canada is cognizant of the ease with which foot and mouth disease can spread. In 1952 Saskatchewan experienced an outbreak of foot and mouth disease, along with the resulting financial cost in loss of livestock export markets. Thus, every effort is being made to ensure the disease does not reoccur in Canada. During the outbreak of foot and mouth disease in the UK in 2001, Canada sent a team of veterinarians to England to gain a better understanding of the disease and its control. Canada strengthened its import regulations and began a successful public information program, including footbaths for all air passengers returning to Canada from countries where the disease existed.

We now realize that the rapid spread of the disease in England was related to the widespread ease with which livestock were transported within England and the continent. The British animal transport industry recognized its role and codes of practice were developed including the disinfecting of all transport vehicles and equipment. Canada has similar codes of practice.

Animal Transportation

Animal transportation is another recent animal issue. With at least 75 000 dogs and cats travelling by air annually in North America and one million day-old chicks in the air every day of the year, it is easy to see the tremendous interest in the safety and well-being of these animals. Unfortunately, it is not possible to obtain accurate figures on the numbers of animals transported by road or by sea.

Initiatives to address this issue have begun at various levels. Some airlines have produced videotapes to inform the public of their responsibility in preparing their pets for air travel as well as for training their ground personnel. Agriculture Canada has a committee made up of representatives of all groups of shareholders with interests in animal transportation. Its responsibility is to provide a working plan to ensure the enforcement of the Health and Animals Act regulations regarding the humane treatment and well-being of all animals being transported in Canada. Recommendations have been made and local pilot studies undertaken to involve local veterinary groups, regional animal-welfare groups, the livestock industry in regional areas, provincial regulators and federal government employees.

There are 2 international animal transportation associations. The Animal Transportation Association has a multidisciplinary membership involving airlines, animal transporters, insurance agents, forwarding brokers, animal-welfare groups, veterinarians and government agencies. The International Air Transportation Association (IATA) is made up of representatives from the airline industry with numerous consultative appointees and observers. IATA produces an operational manual on animal enclosures, for the preparation of animals for travel and for listing international regulations and advisory agencies.

Pet Animals

Many symposia have sought to define the problems associated with pet animals. Discussions have focused on disease, dog bites, the fouling of parks, lawns and gardens, animal control and euthanasia of surplus animals. Despite symposia, books, spay-neuter clinics and public education on responsible pet ownership, pounds and humane societies are still obliged to kill excessive numbers of surplus dogs and cats. In Canada, approximately 500 000 unwanted companion animals are destroyed annually.

Animal Suffering

The dilemma associated with our relationship to animals is discussed in a book by Oxford biologist Marion Stamp Dawkins, Animal Suffering: The Science of Animal Welfare (1980). It provides an outline of the biological approach to animal welfare. Unfortunately, we lack much knowledge about what constitutes pain or distress and about how to recognize latent or masked suffering. To understand the suffering of animals it is necessary to understand better their ethological or behavioural needs, awareness and perception.

Behavioural Needs

The social and behavioural needs of animals have become a science in itself in the late 20th century, although animal behaviourists were active earlier. Science has now proved that animals do have behavioural needs, and some of them can be measured. Furthermore, it is established that the performance of normal behavioural patterns may be crucial for animal welfare. Thus new legislation and new guidelines require that the issue of social and behavioural needs be met. This has been addressed by providing environmental enrichments such as improved enclosures and companionship - either by humans or other conspecific animals - and something the animal can interact with, thus lessening the risk of vices such as pacing, racing, biting or other bizarre behavioural problems.

The study of canine and feline behaviour or companion animal behaviour has become a burgeoning discipline. This should not come as a surprise when one realizes that over 45% of those dogs and cats that are destroyed each year at the owner's request have behavioural or discipline problems that the owner can no longer deal with.

Animal-Human Bond

The closer examination of our relationship to and use of animals has resulted in the development of scientific recognition for the human-companion animal bond. A prominent international organization, the Delta Society, was established in 1981 to promote animal-human interaction. The society provides education and training for the therapeutic interaction of pets with the sick, disabled, elderly and schoolchildren as well as on responsible pet ownership.

In Canada, the Human Animal Bond Association of Canada (HABAC), with origins similar to that of the Delta Society, was established in 1987. HABAC has sought to work with the Delta Society in their programs; to co-operate with the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association and the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies; and to be an umbrella organization to all organizations having similar goals such as animal-assisted therapy, service animals and responsible pet ownership.

In Canada, 3 Pet as Society symposia, the first in 1976, were held well before any in other countries addressed human-animal relationships and responsible pet ownership. In 1992, HABAC was responsible for holding an international congress in Montréal on the theme "Animals and Us," where over a thousand delegates attended from around the world. At this congress the International Association of Human-Animal Interactive Organizations was formed and held its first meeting.

All organizations interested in the bonds between humans and companion animals - including those in the research community studying them - have suggested that humans benefit from reduced stress, lower blood pressure and enhanced socialization. The use of dogs to assist the handicapped (eg, blind and hearing impaired) is already familiar. New knowledge acquired through biomedical research, or through our understanding of and responsibility toward animals themselves, can only lead to an improvement in the health and well-being of both humans and animals.

Animal-Welfare Groups

Many Canadian universities have student organizations concerned with the ethical treatment of animals. In general, such groups do not represent the position of the main student body but they do make their presence on campus known through demonstrations and protests. Rarely do they vandalize animal facilities or personal property, or harass scientists or animal care staff. In this way, they differ from their counterparts in other countries. In the UK, a campaign against Huntingdon Life Sciences was so aggressive - including fire bombings of cars and protests at the private residents of laboratory staff and at financial institutions connected with the laboratories - that the Criminal Justice and British Police Act was strengthened, making it an offence to harass, vandalize and threaten the public.

Humane Societies and other less militant animal-welfare groups have been willing to discuss differences in a rational, nonpolarized manner. Unfortunately, the proliferation of special-interest groups (eg, "Save Our Seals") has diluted the overall objectives of the animal-welfare community. This splintering effect has sometimes frustrated those who take a moderate stand in their attempts to protect animals and eliminate cruel practices. Some consider the efforts of the activists "misdirected humaneness." No one as yet has defined "humaneness," but the question has been addressed by philosophy professor Bernard E. Rollin in his book Animal Rights and Human Morality (1981).

Of the 30 or so organizations devoted to animal welfare in Canada, the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies (CFHS) has the largest membership (200 000, including affiliates). The humane movement is represented by provincial, territorial and municipal humane societies, some of which operate independently. These organizations operate animal shelters and offer humane education programs. Some are involved in animal control.

Many internationally based animal-welfare agencies (Humane Society of Canada, World Society for the Protection of Animals and International Fund for Animal Welfare) have opened secretariats in Canada. For the most part these agencies were initially supported financially with funds and organizational methodology by the parent organization located outside of Canada. Therefore, some of their activities are counter to those favoured by Canadian opinion.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom