Dane-zaa (also known as Dunne-za) are Dene-speaking people from the Peace River area of British Columbia and Alberta. Early explorers called them the Beaver people (named after a local group, the tsa-dunne), however the people call themselves Dane-zaa (meaning “real people” in their language). In the 2021 census, 1,310 people identified as having Beaver (Dunne-za) ancestry, while 220 reported the Dane-zaa language as their mother tongue.

Population and Territory

The Dane-zaa are from what is now the Peace River area of British Columbia and Alberta. They are neighboured by the Sekani to the west, the Slavey to the north, and the Dene Tha (variously called Beaver and Slavey) to the east. The Cree also occupied the eastern part of their territory in historic times. (See also Indigenous Territory.) In the 2021 census, 1,310 people identified as having Beaver (Dunne-za) ancestry.

Pre-contact Life

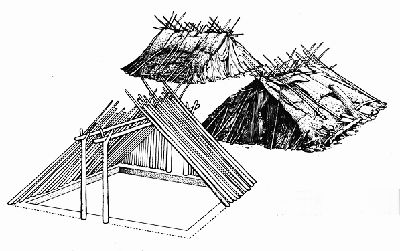

The Dane-zaa traditionally lived in small nomadic hunting groups of 25 to 30 people. Most food came from hunting large game animals: bison in the prairie country near the Peace River, moose in the muskeg and forests, caribou near the mountains, and bears. Before they obtained firearms from fur traders, hunting was often done by groups of people who surrounded animals. (See also Fur Trade.) The introduction of rifles made individual hunters more efficient. Within 25 years of first contact, hunting to supply furs to the traders led to a decline in game populations, particularly bison, which became extinct in the area by 1900.

Colonial History

Alexander Mackenzie passed through Dane-zaa territory in 1793. By 1794, the Northwest Company established a fur-trading post near the present town of Fort St. John. Dane-zaa oral history gives a vivid account of early fur trade history.

As Europeans increasingly encroached on Dane-zaa territories, the Dane-zaa were forced onto smaller parcels of land. (See also Reserves.) As a means of assimilating Indigenous populations, the Canadian government sent Dane-zaa children to residential schools, where they and other Indigenous children were forbidden from speaking their languages and practicing their cultures. Officially launched in 2008, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada sought to guide Canadians through the difficult discovery of the facts behind the residential school system and to lay the foundation for lasting reconciliation across Canada.

Culture

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Dane-zaa came together into larger groups along the Peace River for summer ceremonies at which they sang, danced and played the hand game, a guessing competition between teams of men. Dene games and cultural ceremonies are still practiced in many Dane-zaa communities. The Dane-zaa (particularly children) also participated in vision quests to gain supernatural power from animals. Many Indigenous peoples still participate in vision quests as a means of reconnecting with their culture.

Language

The Dane-zaa call their language Dane-zaa Záágéʔ, though it still appears in many sources as the Beaver language. Dane-zaa Záágéʔ is an Athabaskan (or Dene) language and is therefore closely related to the languages of other Athabaskan-speaking First Nations, including the Sekani, Kaska, Dene Dháh (Alberta Slavey), Tsuut'ina (Sarcee) and Dene Sųłiné (Chipewyan).

Dane-zaa Záágéʔ is spoken in the areas of Doig River, Halfway River and Prophet River in British Columbia, as well as on the Blueberry River First Nations. It is also spoken in Alberta on the Boyer River (Rocky Lane) and Child Lake (Eleske) reserves.

The language is endangered; in the 2021 census, only 45 people in Alberta reported the Dane-zaa language as their mother tongue. That figure is higher in British Columbia (165), but still reflects significant language loss. The Dane-zaa are actively involved in efforts at revitalizing their language. (See also Indigenous Languages in Canada.)

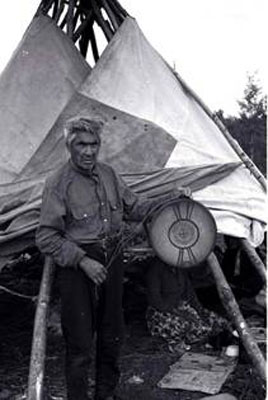

Religion and Spirituality

Before the arrival of Europeans, Dane-zaa practiced their own religious and spiritual belief systems. Religious leaders or prophets were known as the “Dreamers,” and they were active in various social and cultural affairs of the community, such as leading the communal hunts. With the imposition of Christianity, the Dreamers adopted their own version of the religion that blended traditional prophecy and Roman Catholic teachings. The first Roman Catholic missionary, Henri Faraud, visited the Dane-zaa in 1858. The Dreamers tried to help their people understand and anticipate the changes brought about by White people. Although most Dane-zaa had converted to Roman Catholicism since the early 1800s many have since accepted evangelical Protestantism. Many Dane-zaa also combine organized religions with traditional beliefs.

Treaties

The Dane-zaa of Fort St. John signed Treaty 8 in 1900, formalizing their right to live by hunting and trapping. (See also Numbered Treaties.) Their understanding was that the treaty was a peace and sharing agreement between sovereign nations rather than a surrender of title. The Dane-zaa First Nations continue to negotiate with the federal government regarding treaty lands, entitlements, and the number of Dane-zaa First Nation members.

Contemporary Life

Many Dane-zaa continue to live on reserves and approximately half of all registered Dane-zaa live off reserve; there are four Dane-zaa reserves in British Columbia and two in Alberta. Several Dane-zaa First Nations have built new halls that serve as community centres on their reserves. First Nations as well as individuals manage businesses that serve the oil and gas and timber industries.

After a long court case, the former Fort St. John Band was granted the right to negotiate a settlement for the improper transfer of mineral rights to their former reserve land. They have also entered into negotiations with the federal government regarding a shortfall of treaty land entitlement following extensive research to establish the actual number of people when the reserve land was first surveyed and allocated. Much of their former land is developed for farming and petroleum production. However, hunting and trapping are still part of the northern part of their territory and are important activities as sources of food and income and help to maintain a sense of identity.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom