The Constitution of Canada is the country’s governing legal framework. It defines the powers of the executive branches of government and of the legislatures at both the federal and provincial levels. Canada’s Constitution is not one legal document. It is a complex mix of statutes, orders, British and Canadian court decisions, and generally accepted practices known as constitutional conventions. The Constitution has been in constant evolution from colonial times to the present day. The story of the Constitution is the story of Canada itself. It reflects the shifting legal, social and political pressures facing Canadians, as well as their choices as a society.

What is the Constitution?

The Constitution Act, 1867 (formerly called the British North America Act) is of central importance in the Canadian Constitution. It outlines the distribution of powers between the federal and provincial legislatures. The Constitution Act, 1982, which includes the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, is also of high importance.

Unwritten conventions are generally accepted practices. They are not specifically stated in any statute. An example of a constitutional convention in Canada is that the person elected prime minister or premier must have the support of the elected branch of the legislature to remain in power. Another is that seats on the nine-member Supreme Court of Canada should be allocated regionally. These are not “laws” that can be enforced by the courts. But such principles are of the utmost importance to effective constitutional government. (See also Constitutional Monarchy.) During the patriation of the Constitution in 1981, the Supreme Court stated that “constitutional conventions plus constitutional law equal the total constitution of the country.” (See also Patriation Reference.)

The courts will not enforce conventions; they can be implemented only by the people or by the Crown. For example, the Crown has the power to dismiss a premier or prime minister who has clearly lost the confidence of the elected legislature and refuses to resign or have an election called. A government that violated a constitutional convention would almost certainly face electoral defeat; in extreme cases, it could face revolution. Such unwritten principles can be more important than many laws.

According to British and Canadian constitutional theory, settlers bring with them laws from their former home that are appropriate to local circumstances. Such English laws as the Bill of Rights (1689), with its concept of limited constitutional monarchy, and the Act of Settlement (1701), with its doctrine of an independent judiciary, are also features of the Canadian Constitution. So too is the Canada Election Act. Quebec’s Civil Law system is derived from France. From Britain comes the principle of parliamentary supremacy. It is modified in Canada’s federal structure by the distribution of powers and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Both of these were influenced by the American system of government.

Constitutional Evolution, Pre-Confederation

French Colonial Period

Prior to 1663, control of New France was given to chartered companies. They exercised extensive administrative, lawmaking and judicial powers. (See also: Company of One Hundred Associates; Compagnie des Indes occidentales.) It is uncertain what system of law was in effect. In 1663, France’s North American possessions came under direct royal rule. The Coutume de Paris became the civil law of New France.

King Louis XIV of France acted through Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Colbert supervised colonial affairs with two local officials, the gouverneur (governor) and the intendant. The governor also served as a military commander, a negotiator with the Indigenous peoples and an emissary to other colonial outposts. The intendant oversaw civil administration. He was responsible for settlement, finance, public order, justice, and the building of public works. Under royal rule, there were no elected institutions. However, a Sovereign Council met weekly. It consisted of the governor, the intendant, the bishop and five other councillors.

From 1663 to 1675, the councillors were nominated jointly by the bishop and governor; after 1675, they were chosen by the king. The council dispensed justice swiftly and inexpensively. It managed spending and regulated the fur trade and other commercial activities. Limitations, or “servitudes,” exempted civil officials from church discipline; no government official could be excommunicated by the Catholic church for performing his duties, whatever they might entail. The church was also powerless to impose its taxes without the consent of the civil authorities.

(See also Collection: New France.)

British Take Control

During the 18th century, France lost its North American territories to Britain. By the time of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, Acadia was ceded to Britain. France retained control of Île Royale (Cape Breton), Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) and part of modern New Brunswick. France argued that, under the treaty, the Acadians continued to live under French sovereignty, since they lived mostly on the western fringes of the territory.

Caught between rival European powers, the Acadians were expelled by the British in 1755. The French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton fell to the British for the last time in 1758. That same year, the Nova Scotia Legislative Assembly (English Canada’s oldest representative body) was convened in Halifax. (See also Nova Scotia: The Cradle of Canadian Parliamentary Democracy.) When the Seven Years’ War ended with the Treaty of Paris (1763), all of New France came under British rule, with the sole exception of the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. ( See also The Conquest of New France.)

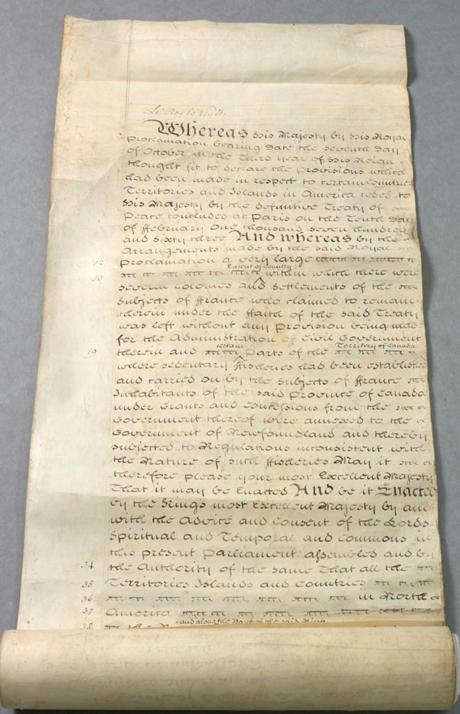

Royal Proclamation, 1763

In keeping with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Governor James Murray was to extend English laws and institutions to Quebec. He was instructed to govern with the help of a council of eight. An elected assembly was planned but did not come to fruition. Murray’s instructions also included a Test Oath for office-holders. Because of the oath’s religious content, no Catholic could conscientiously take it. This provision resulted in all public offices being held by some of the 200 English-speaking Protestants in the colony, and none of the nearly 70,000 French-speaking Catholics. Murray interpreted his instructions in such a way that he could govern through a 12-member appointed council.

English was the official language, but government was conducted in French. The "liberty of the Catholic religion" was ensured. The Proclamation of 1763 also recognized Indigenous land title; it held that Indigenous people could relinquish their land only to the Crown and only collectively.

The substitution of British courts and laws in Quebec created difficulties. The new Court of King’s Bench convened only twice a year. This made justice more costly and less expeditious than it had been under the Sovereign Council. With the abolition of the Coutume de Paris, tenant farmers on seigneurial lands suffered; their rents could now be raised arbitrarily according to English law. Because of the Test Oath, no Catholics could practice law in the new Court of King’s Bench. They were permitted to practice in some lower courts.

(See also Royal Proclamation of 1763 (Plain Language Summary).)

Quebec Act, 1774

The Quebec Act of 1774 introduced a colonial governor and an appointed council of between 17 and 23 members. The Act was silent on the use of French. But a new oath allowed Roman Catholics to accept office. The council was not empowered to impose taxes; that matter was dealt with under the Quebec Revenue Act. The seigneurial system was retained and French civil law was restored. It was supplemented by English criminal law. Governor Sir Guy Carleton was instructed to introduce English commercial law as well, but he did not.

The Act was unpopular in the Thirteen American Colonies for two main reasons. First, it permitted Catholicism. Second, it extended Quebec’s southwest boundary to the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. This impeded westward American expansion. The Quebec Act became one of the “intolerable acts” that prompted the American Revolutionary War (1775–83). However, many historians feel the Act encouraged French Canadian support of continued British rule. (See also Quebec Act, 1774 Document; The Quebec Act, 1774 (Plain Language Summary).)

Constitutional Act, 1791

The influx of Loyalists after the American Revolution led to the creation of more British North American colonies. In 1784, New Brunswick and Cape Breton were created from parts of Nova Scotia. In 1791, Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) was separated from Lower Canada (present-day Quebec), with the Ottawa River forming the boundary.

Under the Constitutional Act, 1791, each of the two Canadas was given a two-house legislature. The executive council was appointed by the governor. He was responsible to the British Colonial Office rather than to the people or their elected representatives. Thus, there was representative government. However, the executive council was not responsible to the elected assembly.

In the early 19th century, various governors appointed personal friends to office. This led to charges that they were governing by clique. (See also: Château Clique; Family Compact; Council of Twelve.) Partly as a result, in 1837, unsuccessful rebellions broke out in both Upper and Lower Canada. (See also: Rebellion in Lower Canada; Rebellion in Upper Canada.)

In the Maritime provinces, Nova Scotia was divided into multiple colonies. This enhanced executive power and weakened the assembly. Cape Breton, which remained separate until 1820, lacked an assembly altogether. Prince Edward Island was joined briefly to Nova Scotia from 1763 to 1769. It got its own legislature in 1769. It was at times in danger of losing it. Newfoundland had an appointed governor. It acquired a representative assembly in 1832.

Responsible Government

Governor General Lord Durham came to the Canadas in 1838 after the rebellions. He regarded French Canadians as unprogressive and lacking in history and culture. This view, of course, outraged French Canadian elites. Durham feared the French Canadians would use any independent political powers it might acquire to frustrate the policies and objectives of the government. He argued for a “fusion” of the legislatures of Upper and Lower Canada into a single government. This would allow the “more reliable” English-speaking elite to dominate.

Durham also felt that the governor’s appointed executive council should enjoy the support of a majority in the elected assembly. This meant the council (Cabinet) would be responsible to the elected assembly and indirectly to the electors, rather than to the Crown or the governor. Local policy would be decided at home. Matters of “imperial interest” — such as constitutional changes, external relations, trade, and the management of public lands — would remain with Britain.

The Durham Report marked the watershed between the first and second British empires. (See also Imperialism.) British colonies, including Canada, began to evolve into self-governing nations. As a result of the report, the Act of Union was passed in 1841. It unified Canada East (formerly Lower Canada) and Canada West (formerly Upper Canada) into the Province of Canada. Each province had equal representation in a shared legislature, even though Canada East had a much bigger population. This was to ensure that the British element had greater representation in the colony.

After some hesitation, responsible government was introduced in 1848. It was adopted first in Nova Scotia and then in the Province of Canada. It was soon in effect throughout British North America. In 1849, Governor General Lord Elgin signed the Rebellion Losses Bill on the advice of his ministers. This affirmed the principle of responsible government. Elgin was also instrumental in introducing French as a language of debate in the Canadian legislature. English, however, remained the sole official language.

(See also: Nova Scotia: The Cradle of Canadian Parliamentary Democracy; Collection: Responsible Government; Editorial: Baldwin, LaFontaine and Responsible Government; Education Guide: LaFontaine, Baldwin and Responsible Government.)

Confederation

The process of governing the Province of Canada became characterized by deadlock. This was due to the differing political priorities between Canada East and Canada West. By 1851, the English-speaking population outnumbered the French. Canada West began arguing for “representation by population” instead of East-West parity. George Brown’s Reform Party advocated for Rep by Pop while the Conservatives opposed it. This political stalemate lasted from 1858 to 1864. In 1864, the parties formed a Great Coalition. Its objective was to unite all British North American colonies.

At the same time, imperial authorities in Britain were letting go of control over Canada. Unoccupied Crown lands were surrendered to the provinces. In 1858, the British submitted to a Canadian tariff imposed on their imported goods. (See Customs and Excise.) And in 1865, the British Parliament affirmed that a colonial law could only be challenged if it was expressly in conflict with an imperial statute that applied to the colony.

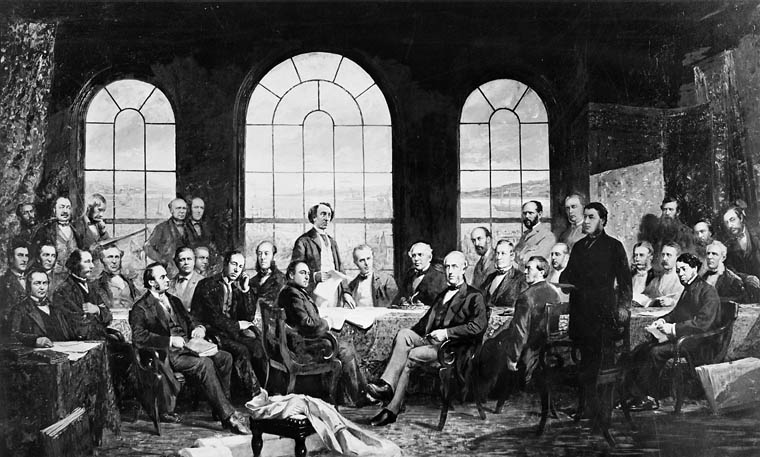

At the Charlottetown Conference in 1864, politicians from Canada East and West met with their counterparts from New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island to discuss the union of their colonies. The Quebec Conference and London Conference saw further discussion. (See also Quebec Resolutions.) Confederation of the provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick received Royal Assent on 29 March 1867. It became official on 1 July 1867.

(See also: Timeline: Confederation; Collection: Confederation; Fathers of Confederation; Collection: Fathers of Confederation; Mothers of Confederation; History Since Confederation.)

Constitutional Evolution, Post-Confederation

British North America Act (1867)

The British North America Act (now called the Constitution Act, 1867) became the founding constitutional statute of the new Dominion of Canada. A federal Parliament of two chambers was established in Ottawa. Seats in the House of Commons were allocated on the basis of population. Seats in the Senate were distributed equally (24 each) among the three existing regions (Ontario, Quebec and the Maritime Provinces).

In 1915, the four Western provinces became a full-fledged region with 24 senators of their own. Newfoundland received six senators upon joining Canada in 1949. The territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut) each have one senator.

The Senate was seen as a guardian of regional or provincial interests. However, it has tended not to play that role very effectively. It has often become divided on partisan lines. Senators usually vote as members of a party caucus rather than as representatives of a region.

(See also Constitution Act, 1867 Document.)

Federal-Provincial Powers

Under the Constitution Act, 1867, broad national matters are centralized with the federal government. These include: defence; postal service; trade and commerce; most communications; currency and coinage; and weights and measures. Powers over property, municipalities, and most private law, are controlled by the provinces. Federal law prevails wherever a conflict occurs in shared areas such as agriculture and immigration, or in any subject matter, except old-age pensions. (See also Distribution of Powers; Federal-Provincial Relations.)

Under the Constitution (which includes all provincial constitutions), Canadian provinces are not all treated as equals. This is in part because they were added or created at various times. Saskatchewan’s founding statute, for example, said that it could not tax the Canadian Pacific Railway. Quebec and Manitoba were required to publish their laws and allow proceedings in their courts and legislatures in both English and French.

The Prairie Provinces, unlike the original four (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec and Ontario), did not own the rights to their natural resources when they entered Confederation. They only received them by transfer from Ottawa in 1930. Ottawa had retained control of these assets on the grounds that it needed the resources for railway building and the settlement of immigrants.

Canada’s territories — Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut — have elected legislatures. However, they also retain a semi-colonial dependency on the federal government. They all fall constitutionally under federal control.

After Confederation, some provinces advanced the Compact Theory of Confederation. It likened the BNA Act to a treaty, and argued that it could be changed only by the unanimous consent of Ottawa and the provinces. Opponents of the theory denied its constitutionality. They argued that the final terms of the BNA Act were never ratified since the Act was not an agreement but a statute of a superior legislature.

Federal-Provincial Conflict

John A. Macdonald, an ardent federalist, was prime minister of the federal government for a total of 19 years (1867–73; 1878–91). On 20 October 1887, premiers Honoré Mercier of Quebec and Oliver Mowat of Ontario met in Quebec City with representatives from New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Manitoba. ( British Columbia and PEI did not participate.) The purpose of the meeting was to promote “provincial rights” against an encroaching federal government.

The provinces objected to the federal power of disallowance. It enabled Ottawa to nullify any provincial law. The premiers called for appointment of senators by the provinces. They also affirmed the right of the provincial Crown to use prerogative powers, such as the pardoning power over provincial offences. Macdonald chose to portray the “malcontents” as Liberals confronting their Conservative foes in Ottawa for partisan reasons.

Another confrontation arose in 1890. Manitoba tried to make English the only official language in the province. It also substituted a single public school system for the former Roman Catholic and Protestant schools. (See Manitoba Schools Question.) In 1895, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council — Canada’s highest appeals court at the time — agreed that the educational rights of the religious minority had been adversely affected. The Committee allowed these groups to appeal to the federal Cabinet for redress.

When the Liberals assumed office in 1896, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier settled the matter by compromise. In the 1979 Forest case, the Supreme Court of Canada decided that the 1890 Manitoba English-only language law was invalid. This cast doubt on the legal validity of 90 years of provincial legislation; it also required all future laws to be bilingual.

(See also: Federal-Provincial Relations.)

Towards Constitutional Independence (1919–31)

In the early 20th century, Canada took more steps towards full independence from Britain. When the First World War began in 1914, Canada was automatically included in the British declaration of war. This was due to constitutional convention. After the war, Canada’s separate signature on the Treaty of Versailles and its membership in the League of Nations symbolized its developing independence.

In 1923, Ernest Lapointe signed the Halibut Treaty without British participation, despite British objections. In 1926, Governor General Lord Byng refused to dissolve Parliament at the request of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King. King portrayed this as a form of imperial interference in Canada’s domestic affairs. However, Byng’s refusal was constitutional. (See King- Byng Affair.)

At the Imperial Conference that same year, the Balfour Report was drafted. It described the self-governing Commonwealth Dominions as autonomous and equal communities within the British Empire. In 1931, the Statute of Westminster stipulated that the British Parliament could no longer legislate for a Dominion unless that country requested and consented to the law.

Other parts of the Statute gave local legislatures the power to enact laws even if they violated colonial policy. This allowed Canada to legislate extraterritorially. For example, it could establish shipping laws for Canadian vessels at sea, or apply criminal law to Canadian military personnel serving abroad. The Statute also affirmed (at least according to the provinces) that provincial jurisdiction could not be unilaterally altered by the federal government.

(See also Statute of Westminster: Canada’s Declaration of Independence.)

A Canadian Crown

After 1931, in constitutional theory, London was no more central politically than was Ottawa or Canberra, Australia. The Crown, formerly indivisible, now became divided. In 1939, Canada made a separate declaration of war to enter the Second World War. Treaties between First Nations in Canada and the British Crown were now deemed to be the concern of the Canadian government. The monarch became king or queen of Canada, with the governor general consenting to all the remaining prerogative powers in 1947.

In 1952, Vincent Massey became the first Canadian-born governor general. He was succeeded in 1959 by Georges Vanier. From that point on, individuals from English- and French-speaking Canada alternated in the governor general’s office.

In 1949, a constitutional amendment allowed Parliament to make constitutional changes that solely affect federal power (e.g., redistribution of seats in the House of Commons). Exceptions were made in sensitive areas (e.g., holding annual sessions of Parliament). Other indications of sovereignty were the Canadian Citizenship Act (1947) and the adoption of the maple leaf flag in 1965. (See also The Great Flag Debate.)

Newfoundland

Between 1934 and 1949, Newfoundland, formerly a self-governing colony, was governed by a British-appointed Commission of Government. It had full lawmaking powers. After the Second World War, debate arose about Newfoundland’s future. Peter Cashin, a former Newfoundland finance minister, advocated a switch to Dominion status. Meanwhile, Joey Smallwood led the pro-Confederation forces that sought to join Canada.

Some Newfoundlanders supported keeping the commission government. In the second of two referenda held in 1948, the pro-Confederation forces prevailed. In 1949, Newfoundland became Canada’s 10th province. It was given six senators and seven members of Parliament.

(See also: Newfoundland and Labrador and Confederation; Newfoundland Bill; Editorial: How the “Canadianized” Community of Newfoundland Joined Canada.)

British Privy Council

Until 1949, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council was Canada’s highest court of appeal. (See also Privy Council.) Some important appeals had been made directly from provincial tribunals to Britain without any participation by the Supreme Court of Canada (established in 1875). The decisions of the Judicial Committee decentralized the centralist provisions of the BNA Act. (See also: Federalism; Federal-Provincial Relations.) They demoted the status of the federal peace, order and good government power and expanded provincial jurisdiction over property and civil rights.

In 1929, the Judicial Committee ruled that women were legal “persons” capable of being summoned to the Senate. (See also Persons Case.) In 1932, the Committee granted power over aeronautics and radio to Ottawa. In 1937, however, it curtailed Prime Minister R. B. Bennett's “New Deal” social program. ( See Bennett’s New Deal.) This gravely reduced federal power over such matters; they were deemed instead to be under provincial jurisdiction.

In 1937, Alberta Premier William Aberhart tried to enact a Social Credit program. However, it crossed into federal jurisdiction, particularly the federal power over banking. When the provincial legislation was not allowed by Ottawa, a bitter confrontation ensued. The courts later upheld the federal position. The issue led to the Rowell-Sirois Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations.

Rowell-Sirois Report: Restructuring Federalism (1937)

The Rowell-Sirois Commission was appointed by William Lyon Mackenzie King’s government in 1937. It made far-reaching economic recommendations for restructuring the Canadian federation. The commissioners said Ottawa should have the exclusive right to levy personal and corporate income taxes and succession duties. In return, the federal government would assume all provincial debt. It would also take on certain responsibilities over relief and unemployment insurance (which the court had just consigned to the provinces). And it would pay the less affluent provinces a “National Adjustment Grant” to enable them to maintain services at the average national level.

Quebec’s Tremblay Commission (1953–56), started by Premier Maurice Duplessis, saw this proposal as too centralist. The Tremblay Commission argued instead for the principle of “subsidiarity.” Duplessis compared federalism to a pyramid. He suggested that as many economic functions as possible should be carried out by local organizations at the base (e.g., municipalities, co-operatives, churches). The federal government, at the top, would perform only limited functions beyond the capacities of local groups. This concept, of course, would strongly reinforce provincial autonomy.

The Rowell-Sirois Commission’s 1940 recommendations were never really implemented. The equalization payments to the provinces achieved a similar purpose. They were begun by Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent after the centralization of powers during the Second World War. In one form or another, federal equalization payments to poorer provinces have continued.

Employment insurance was centralized federally by an amendment. But the richer provinces (Ontario, Alberta, BC) objected to subsidizing the poorer provinces. The federal “spending power” was used to fund family allowances. Shared-cost programs were entered into jointly with the provinces. These costly social programs placed a huge strain on all governments in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This led some politicians to question the constitutionality of universal coverage.

Emergency Powers

By proclaiming the War Measures Act during both the First and Second World Wars and the 1970 October Crisis, the federal Cabinet acquired all legal powers needed to cope with the emergencies. This was true even if such powers fell under provincial jurisdiction. Constitutionally speaking, under the Act, it was almost as if the division of powers did not exist. It was largely for this reason that the War Measures Act was repealed in 1988 and replaced by the Emergencies Act.

The Emergencies Act created more limited and specific powers for the federal government to deal with emergencies. Under the Act, Cabinet orders and regulations must be reviewed by Parliament. This means the Cabinet cannot act on its own, unlike under the War Measures Act. The Emergencies Act also notes that government actions are subject to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Canadian Bill of Rights.

Secession, Patriation and Beyond

Quebec Independence Movement

An important constitutional development in 1969 was the federal Official Languages Act. (See also Official Languages Act (1988).) It declared English and French to be Canada’s “official languages.” An array of government services in both languages were provided to all citizens.

The election of the separatist Parti Québécois in Quebec in 1976 showed that the threat of separatism was real. But in a referendum in 1980, Quebec voters rejected the sovereignty-association option by a margin of 60–40.

Following the referendum, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau promised Quebec constitutional renewal. But a lengthy federal-provincial conference in September 1980 ended in a deadlock. Trudeau then announced that Ottawa would unilaterally add both an amending formula and a Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to the core of a new Constitution. The Charter would replace John Diefenbaker’s 1960 Canadian Bill of Rights. Trudeau noted that federal-provincial negotiators had failed to come up with a constitutional amending formula despite trying nine times since 1927. (See also Federal-Provincial Relations.)

Patriating the Constitution (1980–82)

In the early 1980s, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made a controversial attempt to “patriate” (take back from the British Parliament) and amend (change) the Constitution. (See Patriation of the Constitution.) This pitted Ottawa and two provincial allies, Ontario and New Brunswick, against the eight other provinces. They came to be known as the Gang of Eight.

Central to the debate was whether provincial consent was required to make changes to the Constitution that would affect provincial rights, privileges or powers. In September 1981, the Supreme Court decided that Ottawa did have the legal power to unilaterally seek an amendment through the British Parliament. But it also ruled that, by convention, it was improper to do so without a “consensus” of the provinces. The degree of “consensus” was left undefined but would require at least a clear majority. (See also Patriation Reference.)

Neither Ottawa nor the dissenting provinces had won an outright decision of the court. This made compromise essential. All parties except Quebec reached an agreement on 5 November 1981. Spokesmen for Quebec argued that according to the “duality” principle, the concurrence of both English- and French-speaking Canada was required for basic constitutional change. They also argued that the absence of one “national” will created, in effect, a veto on the agreement.

All the other parties denied the existence of the “duality” principle in the form claimed by Quebec. Left unresolved for future consideration were such knotty problems as constitutional revision of the division of powers and institutional reform of the Supreme Court, the Senate and the Crown. Still, the Constitution was renewed and patriated from Britain in 1982. The Charter of Rights and an amending formula were added to the document. The amending formula (the criteria that would have to be met to make future changes) required the approval of the federal Parliament and the legislatures of seven provinces representing at least 50 per cent of the population. This became known as the 7/50 rule.

(See also: Editorial: The Canadian Constitution Comes Home; Editorial: Newfoundland’s Contribution to the Patriation of Canada’s Constitution.)

Meech Lake Accord (1987)

After refusing to put its provincial signature on the patriated 1982 Constitution, Quebec’s acceptance finally seemed secured in June 1987. The first ministers of the federal and provincial governments reached agreement on a series of reforms spelled out in the Meech Lake Accord. (See also Meech Lake Accord: Document.) The deal was reached earlier in the year on the initiative of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

Under the Accord:

- Quebec was recognized as a “distinct society.” Its legislature and government were empowered to preserve and protect the province’s distinct identity. English-speaking Canadians within Quebec, and French-speaking Canadians outside its borders, were also constitutionally acknowledged.

- Parliament and each provincial legislature had to accept the Accord within three years of the passing of Parliament’s enabling resolution. Only in this way would the Accord’s provisions be entrenched in the Constitution. Any change in the proposals required unanimous agreement.

- All provinces would be given a share in the immigration process.

- Making any of the northern territories into provinces would require the consent of all federal and provincial legislatures. This was different from the Constitution Act, 1982; it said such a change would require seven provinces with half the country’s population (the 7/50 rule). The simple federal statute required before 1982 was also nullified.

- Provinces would be able to opt out of programs that fell under the federal spending power (e.g., a national day-care program; or a minimum guaranteed annual income). They could also receive reasonable compensation from Ottawa to fund their own programs, so long as those programs “conformed to the national objectives.”

- Constitutional changes to the Senate or the Supreme Court would need the approval of all federal and provincial legislatures.

- As vacancies arose in the Senate and the Supreme Court, provinces would submit candidates to the federal government for appointment. The only exception would be the chief justice, who would be appointed by the federal government from among the sitting members of the Supreme Court. Three of the nine members of the Supreme Court would be from Quebec and would be trained in civil law.

Collapse of the Meech Lake Accord (1990)

According to polls, public support for the agreement was more than 66 per cent in 1987. By July, the House of Commons (by a vote of 242–16) and all the provincial legislatures except Manitoba and New Brunswick had passed the Accord. However, opposition grew in the media and among certain interest groups: those representing Indigenous peoples; women’s groups; Francophones outside Quebec; and the territories, which believed the Accord would prevent them from ever attaining provincial status. In 1989, a Manitoba task force challenged the legality of the distinct society clause and other aspects of the Accord.

Meanwhile, governments changed and new premiers, such as Frank McKenna of New Brunswick, voiced their opposition. (The New Brunswick legislature gave its approval in 1990.) Eventually, opposition coalesced around Newfoundland premier Clyde Wells. He strongly objected to the distinct society clause. His government rescinded its approval in April 1990.

Desperate to save the Accord, Mulroney called the premiers together in June 1990. On 9 June, the First Ministers emerged with a signed agreement. Wells’s approval was conditional, he said, on the approval of the “Newfoundland people or the legislature.”

However, procedural delays initiated by Manitoba MLA Elijah Harper threatened to extend Manitoba’s approval beyond the deadline. As a result, Wells refused to take a vote in the Newfoundland legislature on the grounds that the situation in Manitoba made the point moot. The deadline expired and the Accord died. The result was bitterness and frustration. Many Québécois interpreted the Accord’s failure in English Canada as a rejection of Quebec. Support for separatism soared in Quebec. The end result was the 1995 Quebec Referendum.

(See also: Editorial: The Death of the Meech Lake Accord; Maclean’s Article: Meech Lake Ten Years After.)

Constitutional Forums (1990–92)

A new round of negotiations began even before the Meech Lake Accord died. In February 1990, the Quebec Liberal Party established a committee to study options if the Accord failed. In June, Quebec premier Robert Bourassa announced that he would not attend constitutional talks; he would only deal bilaterally with Ottawa. Later that month, Bourassa and Jacques Parizeau announced a special Joint Commission to study Quebec’s relationship with Canada. Hearings began in November with co-chairs Jean Campeau and Michel Bélanger.

Meanwhile, on the federal front, Mulroney launched the Citizen’s Forum on Canada’s Future. It was tasked with answering criticisms that the constitutional process was too closed. The Forum began in November 1990 and was chaired by Keith Spicer. Finally, in December, a special 17-member Joint Senate-Commons Committee was created to come up with a new amending formula. Gerald Beaudoin and Jim Edwards were co-chairs. By December, eight provinces had started or finished constitutional investigations.

Bélanger-Campeau received some 200 briefs and 600 submissions. They finished their hearings on 20 December 1990. One of their first reports stated that the cost of Quebec independence would be minimal. The Committee recommended that a referendum on sovereignty be held if Quebec did not receive a suitable offer from the rest of Canada by October 1991.

In January 1991, the Allaire Committee recommended that the Senate be abolished and that Quebec receive exclusive power over its communications, energy, environment, agriculture, and regional development. The Quebec Liberal Party adopted the Allaire Report but substituted an elected Senate. In May, the Quebec legislature introduced a bill for a referendum to be held by October 1992.

To coordinate the various negotiations and recommendations, Mulroney named Joe Clark minister responsible for Constitutional Affairs in April 1991. Yet another public forum was created in June when the Parliamentary Committee on the Constitution was created. Dorothy Dobbie and Claude Castonguay were co-chairs.

The Edwards-Beaudoin Commons Committee reported on the amending formula in June 1991. It recommended:

- Taking two years, not three, to ratify constitutional changes.

- A “regional” veto.

- A national referendum for major changes.

- Unanimous consent for changes involving the monarch, language, and provincial control of resources.

- Requiring the consent of the federal Parliament and the legislatures of Ontario, Quebec, two Western and two Atlantic provinces for all other changes.

In June, the Spicer Commission released its report. It recommended that the government review its institutions and symbols to foster a sense of country; that Quebec be recognized as a unique province; that there be a prompt settlement of Indigenous land claims; and that the Senate be reformed or abolished.

In September 1991, the Dobbie-Castonguay Parliamentary Committee released its proposals in “Shaping Canada’s Future Together.” The proposals included: recognizing Quebec as a “distinct society”; entrenching Indigenous self-government in the Constitution within 10 years; including a “Canada clause” (elaborating certain values, such as egalitarianism and diversity) in the Constitution; and electing a Senate with more powers and “equitable” (but not equal) representation. Castonguay resigned from the troubled committee in November. He was replaced by Gerald Beaudoin.

In March 1992, the now “Dobbie-Beaudoin” Committee recommended a Quebec veto on all constitutional change; recognition of Quebec as a “distinct society”; and an elected, effective and “equitable” Senate subordinate to the House of Commons.

Clark used the report as a basis for negotiations. He set a deadline of 31 May 1992 for Ottawa and the provinces to come up with a constitutional offer for Quebec. He finally reached a deal with nine English-speaking provincial premiers in July. The deal included a “Triple-E” Senate — elected, effective and equitable.

Failure of the Charlottetown Accord (1992)

Clark’s deal was met with a lukewarm response by Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa. However, it did bring him back to the table in August. The First Ministers reached a new agreement on 28 August.

The key points of what became known as the Charlottetown Accord included: a Social Charter; elimination of provincial trade barriers; a Canada clause with commitments to Indigenous self-government and recognition of Quebec as a distinct society; a veto for all provinces on all changes to national institutions; a new 62-seat Senate (six for each province and one for each territory); and 18 new seats in the House of Commons for Ontario and Quebec, four for BC and two for Alberta. (See also Charlottetown Accord: Document.)

The Accord was ultimately rejected by Canadians in six provinces and Yukon in a national referendum on 26 October 1992.

Second Quebec Referendum (1995)

As a result of the failure of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords, a second Quebec referendum on separatism was held in the fall of 1995. The vote on separation was narrowly defeated. The “No” side won with only 50.58 per cent of the vote. It was followed by a number of political and legal developments. Jacques Parizeau, the premier of Quebec who had led the pro-separation side, resigned. Lucien Bouchard, the former leader of the Official Opposition in Parliament (the separatist Bloc Québécois), became premier of Quebec.

In September 1997, the premiers of nine provinces (Quebec’s Bouchard was absent) agreed at a meeting in Calgary to a new approach to preserve Canadian unity. The so-called Calgary Declaration proposed that all provinces, while diverse, possessed equality of status. It also recognized the unique character of Quebec society, including its culture and tradition of civil law. Within a year, all provincial legislatures except Quebec had endorsed the declaration.

(See also Maclean’s Article: Revisiting Mistakes of the 1995 Quebec Referendum.)

Constitutional Veto Law (1996)

Following the near miss of the 1995 referendum, the government of Prime Minister Jean Chrétien passed a law that recognized Quebec as a distinct society within Canada. It also gave the provinces vetoes on constitutional change. The law requires the federal government to get consent for any proposed amendment from each of Quebec, Ontario and British Columbia, as well as at least two provinces representing half the populations of both Atlantic Canada and the Prairies. (It effectively gives Alberta a veto).

This 1996 veto law, however, is largely a political measure. It does not carry the same legal weight as the amending formula in the Constitution Act, 1982. By that formula, most constitutional change requires the approval of Parliament plus any seven provinces; and those provinces must make up at least 50 per cent of the population (the 7/50 rule). Unanimous federal-provincial consent is required for major changes to the country’s governing institutions.

Clarity Act (2000)

After the 1995 Quebec referendum, Chrétien referred the question of separation to the Supreme Court. In the Quebec Secession Reference case, Chrétien’s government asked the Court if it was legal under both constitutional law and international law for Quebec to unilaterally secede from Canada.

The Court’s nine justices said unilateral secession would be illegal without a formal constitutional amendment. However, they added that if a clear majority of Quebecers voted in favour of separation based on a clear referendum question, then the federal and provincial governments would be constitutionally obligated to engage in good faith negotiations with Quebec on the issue. The Court also said any separation must adhere to basic principles such as the rule of law, protection of minorities, and democracy. The Court did not say precisely what would be considered a clear majority or a clear question. It left this up to “political actors” to determine.

The Chrétien government responded with the Clarity Act. It was introduced in Parliament in 1999. It was passed by Parliament and became law the following year. The Act was controversial, especially in Quebec. It gives the House of Commons the exclusive power to determine whether a referendum question on separation is clear and whether there is a clear majority in a referendum vote.

Quebec’s Parti Québécois government reacted to the Clarity Act by passing Bill 99. It says the province can unilaterally separate from Canada following a referendum vote of 50 per cent plus one. It is unclear whether Bill 99 or the Clarity Act would withstand constitutional scrutiny. Neither law has been tested at the Supreme Court.

Following his election in 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper introduced a motion in the House of Commons. It recognized the Québécois people “as a nation within a united Canada.” The motion received majority support in the House. However, Harper’s intergovernmental affairs minister, Michael Chong, resigned over of the motion. He believed it could be interpreted as promoting ethnic nationalism in Canada.

Senate Reform

Political efforts to reform the Senate have been underway for decades. Reformers have tried to change the Senate from an unelected chamber with members appointed by the prime minister into an elected body similar to the House of Commons. However, these attempts have been hamstrung because the Senate is a creature of the Constitution.

In 2011, the Conservative government of Stephen Harper introduced the Senate Reform Act in Parliament. It sought to impose nine-year term limits on senators (who can hold office until age 75), and to allow provinces to elect senators if they choose to do so. The legislation was challenged by the Quebec government. In 2013, the Quebec Court of Appeal ruled the Act unconstitutional. It said the changes could not be made by Parliament alone and required a constitutional amendment.

The Harper government referred the matter to the Supreme Court. In 2014, the Court ruled unanimously that any substantial change to the Senate would require a constitutional amendment in line with the 7/50 rule (the consent of seven provinces with at least 50 per cent of Canada’s population). The Court also said that abolishing the Senate would require the unanimous support of all 10 provincial legislatures and the federal Parliament.

Harper was unwilling to undertake the political negotiations with the provinces needed to obtain such consent. He declared Senate reform a dead issue for the foreseeable future. “We’re essentially stuck with the status quo for the time being,” he said.

See also: Constitution of Canada; Constitutional Law; Constitutional Monarchy; Peace, Order and Good Government; Constitution Act, 1867; Constitution Act, 1867 Document; Statute of Westminster; Statute of Westminster, 1931 Document; Patriation Reference; Patriation of the Constitution; Constitution Act, 1982; Constitution Act, 1982 Document.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom