Dance

Dance is a human behaviour characterised by rhythmic movement of the body. It is often, though not invariably, accompanied by music or drumming. Dance happens in theatres and in movies, in night clubs and in church halls (see Dance, Recreational). It happens in our homes. It has an enormous range of physical manifestations and motives.

People have danced since the beginning of recorded history. Some authorities consider dance an instinctive human response to the rhythms of the natural world, from the cycle of day and night to the continuous beat of the human heart. It stems from the same impulse that gave birth to music.

Down the ages people have danced for many different reasons: as a ritual form of religious devotion, as celebration of a momentous event, as a social diversion, as a mating ritual, as entertainment, as a pleasing form of exercise, as a form of physical or psychological therapy, as expression of something that cannot find its voice in words.

People dance in groups and individually. People dance with deliberate intent and at other times as a spontaneous response to excited emotion. Sometimes they learn how to dance (see Dance Education). At other times they just do it. Thus we speak of someone "dancing for joy". Dance is never purely accidental.

From earliest times dance has also been performed (see Dance History ). A person or group has danced while others have watched. A primitive rain dance might be the preserve of a select group, performed for and observed by the broader community. In religious ritual the dancing has often been restricted to privileged individuals.

In bygone days, dancing girls were often required to perform to please their masters. In ancient dramatic presentations, the audience was expected to sit still while others danced, responding intellectually and imaginatively to the visual stimulus of other bodies in motion.

Many of these distinctions have survived. Today, in "exotic" dance clubs around the world, women still perform to delight their paying "masters", although the advances of democracy and feminism mean that it is sometimes the men who dance to please women.

Other dances have become transformed by the passage of time. Ancient temple dances have become a theatrical entertainment, divorced from their original religious purpose. National dances that helped forge a bond and identity within a particular ethnic group may continue in this form while at the same time being turned into "folkloric" theatrical entertainment for other communities. Sometimes what began as social or Folk Dance has only survived as entertainment.

However, today certain forms of dance are exclusively theatrical, even though their roots can often be traced to social and religious origins. For example, what we now call Indian classical dance is a highly stylized form that has always required great expertise but whose antecedents are the religious dances of ancient India. What we now call Ballet is equally stylised although it has evolved from the court entertainments of Renaissance Europe. Today's ballet choreographers often choose to incorporate movement forms derived from other traditions.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the North American pioneers of what came to be known as Modern Dance believed they were restoring the purity of dance as it had existed in ancient Greek or Asian communities. The various Eastern European dance troupes that today provide spectacular entertainment for audiences of often different backgrounds have refined steps that may have originated in the village communities of Hungary, Poland, Georgia and Ukraine (see, for example, Canada's Ukranian Shumka Dancers).

Theatrical dance does not necessarily occur in isolation. It has often been combined with mime, a form of gesture designed to mimic recognisable human behaviour, or with music, song and dramatic action to help narrate and enliven a complex story. Nowadays we can find dance incorporated into animated works of conceptual visual art. Dance on film and video (see Dance and The Media), while providing a way of recording and broadcasting established conventional theatrical dance forms, can also be used to create original forms that would not be achievable in "live" dance.

Theatrical dance itself has increasingly drawn on other artistic forms - visual art, music, film, holography, computer animation and the spoken word - to create complex and unique forms of expression.

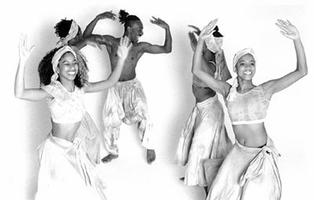

In Canada, because of our multicultural heritage, we can find a richer and more complex range of these various dance expressions than in many other countries. Menaka Thakkar combines the dance she learned in India with the modern dance forms she has learned in Canada. As an immigrant from Haiti, Eddie Toussaint used both jazz dance and classical ballet to create works inspired by the folklore of Québec. When Celia Franca from England founded the National Ballet of Canada she set out to provide classical ballet in the grand European tradition. A much younger company such as Ballet British Columbia takes the classical ballet tradition and tries to push it to its expressive limits. In Canada we have dancers of African or Caribbean heritage returning to explore and preserve the dances of their own cultures. We have traditional Spanish flamenco performed by dancers who may or may not have Spanish ancestry. We have dancers of different ethnic backgrounds performing Balinese or Indian classical dance. We have tap dancers practising a highly rhythmic form that derives from Celtic step-dancing but which owes much to the syncopation of African-American culture. We can find aboriginal peoples still performing their traditional dances or branching out to embrace and incorporate their own way of dancing with theatrical forms developed in other cultures. Once-distinct theatrical forms - ballet, modern, "ethnic" -have borrowed from and combined elements of each other's distinct movement idioms to create new hybrid dance or "crossover" forms.

Dance has thus become fluid and multifaceted, enriched beyond measure by the sharing of cultures and the easing of once-rigid cultural and aesthetic traditions. The result, however, is to make dance much harder to categorise than it might have been even fifty years ago. Definitions, while convenient, are thus also artificially limiting.

Dance, especially theatrical dance, is also the story of individuals - dance teachers, performers, choreographers, directors - who have helped propagate and develop the art form. It is the story of institutions that have provided a context or infrastructure that nurtures creative dance endeavours.

Dance, though its shapes and purposes may have changed beyond recognition, remains as vital and inherent a part of human life as it ever did.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom