Diabetes mellitus, commonly referred to as diabetes, is a disease in which the body either produces insufficient amounts of insulin or cannot use insulin properly. There are two main types of diabetes: type 1 and type 2. Treatment for the disease received a monumental breakthrough when a team of researchers at the University of Toronto (Frederick Banting, Charles Best, John Macleod and James Collip) isolated insulin between 1921 and 1922.

Background and Symptoms

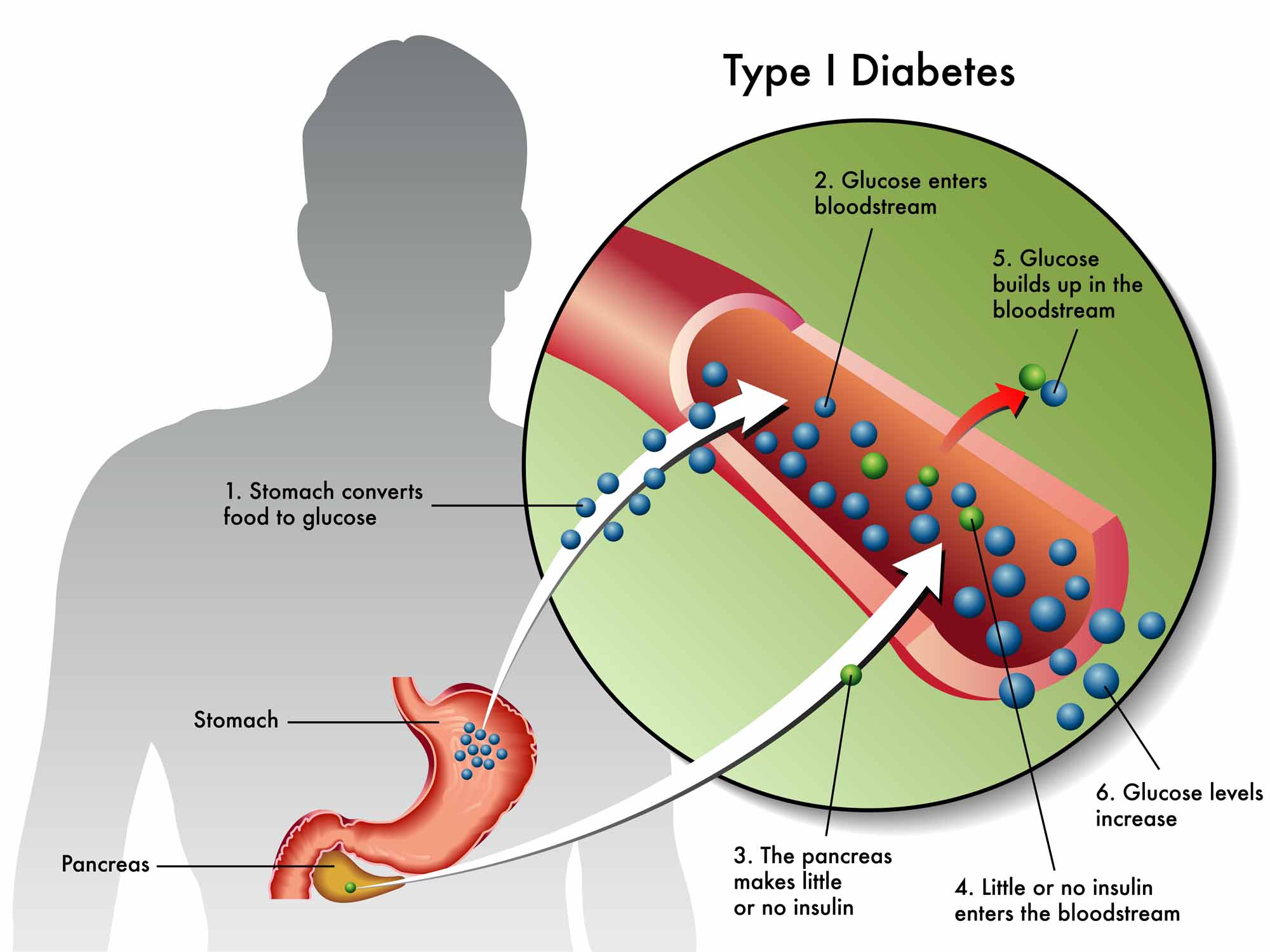

Everyone needs insulin to break down food. What and how much someone eats affects blood glucose levels. When someone has diabetes, there is either not enough insulin in the body or the body cannot use the insulin it produces. Rather than being used as energy, glucose in a diabetic person is stored in the body’s cells and collects in the bloodstream. Over time, elevated blood glucose can cause serious damage to the body. Specific symptoms include fatigue, thirst, frequent urination, damage to nerves, blurred vision and muscle cramps. Even when diabetes is controlled, the insulin supply of the body is limited.

Types of Diabetes

There are two main types of diabetes, type 1 and type 2, as well as related conditions including prediabetes and gestational diabetes.

Type 1 Diabetes

Type 1 diabetes is found in 10 per cent of people with diabetes. Also known as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, type 1 was formerly called juvenile-onset diabetes because it generally develops at a young age. Autoimmunity is a major cause of type 1 diabetes, meaning that the body mistakenly attacks pancreatic islets (clusters of insulin-producing cells in the pancreas) with antibodies (proteins produced by the body to remove harmful substances), ultimately destroying them. Insulin cannot be produced as a result, and external insulin sources are required. Type 1 diabetes is not currently known to be preventable.

Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 is the most common type of diabetes, found in about 90 per cent of those with the disease. Also known as non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, it was formerly called mature-onset diabetes because the majority of patients are diagnosed in adulthood. While type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease, type 2 is a metabolic disorder. In people with type 2 diabetes, the pancreas does not produce enough insulin, and/or the body cannot properly use the insulin it makes. Obesity is common in patients with type 2 diabetes. Unlike type 1 diabetes, type 2 may be prevented through healthy, active living. If diagnosed, it can be mitigated through lifestyle changes.

Prediabetes

Prediabetes is a condition in which blood glucose levels are high but not quite at the level for type 2 diabetes. Some people with prediabetes later develop diabetes. Prediabetes can be treated through lifestyle modifications such as exercise and healthy, low-fat meals. People with prediabetes and metabolic syndrome — which involves high blood pressure, abnormal cholesterol levels and middle abdominal obesity — have a higher risk for developing diabetes than people without metabolic syndrome.

Gestational Diabetes

Gestational diabetes mellitus is diabetes first diagnosed during pregnancy. It is a temporary condition lasting the length of the pregnancy and affecting 3 to 20 per cent of pregnant women in Canada per year. If left untreated, gestational diabetes can lead to heavier babies (4 kg and up) and difficult births. In addition, both baby and mother are at a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes after the pregnancy

Prevalence

The prevalence rate of diabetes in Canada nearly doubled between 2000 and 2010, according to estimates from the Canadian Diabetes Association. In 2010, 7.6 per cent of Canadians had the disease. The rise of diabetes is due to a number of different factors, including an aging population and increased levels of inactivity and obesity. For example, according to Statistics Canada, obesity among Canadian adults was nearly 25 percent in 2011–2012, a rise of 17.5 per cent from 2003. Moreover, the actual number of obese Canadians may be higher, as surveyed individuals self-report information to Statistics Canada and may underestimate their weight and overestimate their height.

The prevalence of diabetes is higher among Aboriginal people, despite being rare among these populations until the second half of the 20th century. Aboriginal people in Canada are a diverse group, including First Nations, Inuit and Métis, living both on and off reserves across the country. As a result, it is difficult to pinpoint a prevalence rate for the group as a whole; however, studies consistently show rates of diabetes three to five times higher among First Nations compared to the general population. Similarly, prevalence among Métis and Inuit is comparatively high and increasing rapidly.

The high rate of diabetes among Aboriginal people is due to a number of factors, stemming primarily from a history of colonization that marginalized Aboriginal people and devalued their traditional ways of life. For many, this marginalization has led to discrimination, poverty and limited access to health care — all of which can lead to a variety of health concerns, including diabetes.

Treatment

The goal of diabetes treatment is to control blood glucose levels. How this is accomplished depends on the individual and the type of diabetes they have.

Type 1

People with type 1 diabetes must take insulin, which is injected beneath the skin because digestive enzymes make it unavailable from the gastrointestinal tract if taken orally. The number of injections and their timing throughout the day depends on the individual.

Type 2

In many cases, type 2 diabetes may be prevented in at-risk individuals through lifestyle changes including increased physical activity, weight loss and a reduction in saturated fat, sugar and refined grains, coinciding with an increase in fruits and vegetables, fiber and whole grains.

Similarly, once diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, individuals can manage their illness through lifestyle changes and, in certain cases, enter remission. Regardless of whether or not a patient’s blood glucose levels return to normal, studies consistently show that lifestyle modification does, at minimum, dramatically reduce the likelihood of developing complications associated with the illness. In addition to lifestyle changes, some individuals require medication and/or insulin.

Complications

People with diabetes are at a higher risk for other illnesses, including heart disease, kidney failure, foot problems (due to decreased circulatory function) and blindness.

Canadian Research

While the earliest known mention of diabetes is attributed to an Egyptian doctor in 1552 BCE, effective treatment depended on the knowledge of insulin — something that wasn’t discovered until the late 19th century. Since then, Canadians have made significant contributions to diabetes research.

Isolating Insulin

Between 1921 and 1922, Frederick Banting and Charles Best, under the direction of John Macleod, isolated insulin in a lab at the University of Toronto. These pancreatic extracts were then purified and made safe for human injection by biochemist James Collip.

Prior to the success at U of T, several researchers had also proved that pancreatic extracts were capable of lowering the blood sugar of both dogs and humans. However, the U of T team was the first to purify the substance so that it could be used in humans without toxic side effects. In 1923, Banting and Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize for medicine (Banting shared his prize money with Best, and Macleod with Collip).

The Edmonton Protocol

Research at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, led by James Shapiro, produced a new treatment for type 1 diabetes, known as the Edmonton protocol. The procedure involves withdrawing islet cells from donated pancreases and injecting these cells into a person with diabetes. The cells are placed into the patient's liver and cause the production of insulin. The first successful procedure was conducted in March 1999 at the University of Alberta Hospital.

The University of Alberta Hospital remains a world leader in this procedure. In 2012, doctors at the hospital performed over 60 islet transplant procedures — around 10 times more than any other facility. As of 2013, approximately 1,200 procedures have been performed across the world. However, the shortage of available donor organs remains a barrier to widespread access to this treatment method.

New Drugs

Over the course of his career, Daniel Drucker, a researcher and endocrinologist at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, developed two new groups of drugs for type 2 diabetes. Many people using medication to treat their type 2 diabetes experience weight gain and hypoglycemia. Drucker’s drugs, however, are able to manage insulin secretion and blood glucose levels without these common side effects. In 2014, Drucker was awarded the Manpei Suzuki International Prize for Diabetes Research.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom