During the 20th century, the federal government established racially segregated “Indian hospitals” for the treatment of First Nations and Inuit peoples in Canada. With the coming of medicare in the late 1960s, the government began to close most of the Indian hospitals. Between 1936 and 1981, the federal government was responsible for 33 Indian hospitals. In 2018, former patients of Indian hospitals filed a class action lawsuit against the federal government. The class action lawsuit was settled in 2025.

Origin and Definition

Indian hospitals originated from federally-funded Christian missionary efforts to provide rudimentary hospital care on some reserves in the late 1800s and early 1900s. After the Second World War, the government aggressively expanded its system of Indian hospitals, which admitted patients based on Indian status, rather than disease. By 1960, the government owned 22 hospitals with more than 2,200 beds, mostly in Ontario and westward.

Indian hospitals did not provide Indigenous medicines, midwives or holistic notions of illness and its treatment. To the contrary, the hospitals were intended to further assimilationist goals and replace traditional healing with biomedicine. There were never any medical training programs for Indigenous people in the Indian hospitals. Although the institutions were originally justified to isolate tuberculosis, they functioned as racially segregated general hospitals. Certainly many people were made well in these hospitals, but patients, often far from home, recall loneliness, vulnerability, fear and, for some, abuse in strange institutions where medical staff did not understand their cultures and languages.

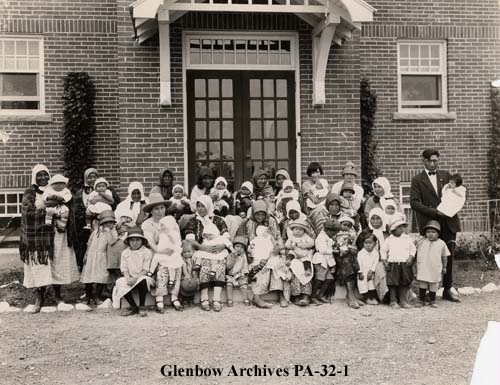

Early Christian Missionary Hospitals

After the late 1800s, the federal Department of Indian Affairs provided limited financial support for modest cottage hospitals operated by Christian missionaries, often affiliated with their residential schools, which supplied most of the patients. Missionaries and the government tried to repress the work of Indigenous healers and midwives, forcing them to practise in secret. It was not unusual for communities to consult their traditional healers and use their medicines for some illnesses while relying on Western biomedicine to treat illnesses that were brought by settlers. First Nations patients were rarely welcomed into hospitals established in settler societies in the West, though some hospitals provided minimal care in segregated “Indian wings” or “Indian wards.”

Establishment of Indian Hospitals

Most Indian hospitals were established in buildings that the government already owned, such as residential schools and facilities of the armed forces. The large, open wards suitable for the armed forces that only treated men were quite inappropriate when the patients also included women and children. The buildings were often overcrowded, and fire was a constant concern. There was limited government funding for needed renovations to stop the dangerous spread of disease because health care for Indigenous people was not a priority. At the two Indian hospitals opened in the 1930s, the Fort Qu’Appelle Indian Hospital in Saskatchewan and Dynevor Indian Hospital in Manitoba, the government found that they could operate at half the cost of care in community hospitals, which encouraged a rapid post–Second World War expansion of Indian hospitals.

Though they were never consulted, many Indigenous communities that had been suffering for years from poverty and overcrowded housing that led to disease welcomed the promise of better health and hospital care similar to what settler society enjoyed. But Indian hospitals were not like the hospitals in surrounding non-Indigenous communities. The poor living conditions at the root of much disease remained.

Many First Nations also welcomed Indian hospitals as the state’s recognition of its legal and treaty responsibility for health care. Those who signed the 11 Numbered Treaties understood health care and medicines to be included in the treaties’ terms. These promises were discussed during many of the treaty negotiations, but they failed to appear in the written text. The sole exception was Treaty 6 (1876), which promised Indigenous signatories and their people a “medicine chest.” Every year when treaty annuities were paid, vaccinations and other medical care confirmed the clear link of health care to the treaty relationship. The government did not share this interpretation, however, instead claiming that it accepted only a humanitarian or moral obligation to provide health and hospital services for Indigenous people, specifically in order to protect the rest of the Canadian population from disease.

Postwar Expansion of the Indian Hospital System

In 1945, the Indian Health Services became part of the newly created Department of National Health and Welfare. A different arm of that bureaucracy would eventually implement the social safety net that included social services and health care insurance changes, such as medicare. (See also Health Policy.) To start, in 1948, it provided annual matching public funds for provincial health care projects, such as disease control, medical education and hospital construction.

Hundreds of new hospitals offered settler communities modern health care and created tremendous opportunities for nurses and doctors. Indian Health Services had difficulty finding medical professionals willing to work for low civil service wages in its overcrowded and poorly equipped Indian hospitals. In several communities, the Indian and local hospitals were literally side by side. Indian hospitals reflected and constructed racial inequality by making it seemingly natural that modernized hospitals would be “white” hospitals, and that Indigenous people were somehow less worthy of care. Under the expanded postwar Indian hospital system, the cost of care continued to be half that of surrounding community hospitals’ rates, with dire consequences for Indigenous patients.

Treatment of Indigenous Patients

Tuberculosis treatment in the 1940s and 1950s began to change from months and years of bed rest to lung surgery and finally to effective antimicrobial medications. Provincial tuberculosis sanatoriums emptied as outpatient treatment became the norm. But treatment for Indigenous patients was different.

Indian Health Services sent First Nations and, especially, Inuit patients from their northern homes to fill southern sanatoriums, often for years at a time. In sanatoriums and Indian hospitals, Indigenous patients underwent invasive chest surgery and drug treatment because they were not seen as capable of managing their condition at home like non-Indigenous patients. Survivors recall feeling lonely and vulnerable at the hands of ever-changing medical staff. The hospitals also provided opportunities for medical experimentation, most often without the patients’ consent. Fort Qu’Appelle hospital conducted experimental trials of the BCG vaccine for tuberculosis on infants; the Camsell Indian Hospital in Edmonton undertook a 1956 trial of various different preparations of the common anti-tuberculosis drug para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS), as well as clinical trials of thyroid-stimulating hormone for a study of hypothyroidism in “Native races.” Rambunctious children were often physically restrained in their beds, or by plaster casts on both legs. Patients in hospitals far from home often did not understand the language, and they struggled to understand their treatment, if it was explained to them. Caregivers, many overworked and underpaid, took out their frustrations on patients. Children without family nearby were particularly vulnerable.

Many patients had no choice but to stay in Indian hospitals, regardless of the treatment they received. The Indian Act was amended in 1953 to include the Indian Health Regulations that made it a crime for Indigenous people to refuse to see a doctor, to refuse to go to hospital, and to leave hospital before discharge. The RCMP arrested patients and returned them to hospital or sent them to jail. However, the government would not return those who died at Indian hospitals to their communities unless the family paid the costs. Many were buried at the nearest cemetery in unmarked graves, forever lost to their families.

Closing Indian Hospitals

Indian hospitals were understaffed and underfunded because public funds went to build, equip and staff modern hospitals in non-Indigenous communities, leading to national programs of hospital insurance (1957) and then health insurance or medicare (1968). By the 1960s, the government planned to close Indian hospitals and instead fund community hospital expansion to accommodate First Nations patients. Local organization, particularly (but not exclusively) in Treaty 6 communities, resisted government plans to close the hospitals. Certainly, Indigenous communities recognized the many problems at the underfunded and poorly equipped Indian hospitals. Nevertheless, the hospitals, especially those near reserve communities, had also become valued institutions providing needed wage labour, though always in lower paid support positions, such as domestic maid, ward aide and janitor. First Nations hospital workers served as translators and cultural brokers, making patients more comfortable by speaking to them in their own languages.

However, activists argued that government funds that were meant for their health care should be used to improve the underfunded Indian hospitals, not given to settler community hospitals. In the 1960s, First Nations organizers at North Battleford Indian Hospital in Saskatchewan refused to pay provincial hospital and health taxes, arguing that the medicine chest clause meant that they had a treaty right to health care. It was not about the money but the larger principle about treaty rights. The government took them to court, where the local magistrate agreed that the treaty right existed for all Indians under the Indian Act. The government appealed the decision, and on appeal, the court decided that the medicine chest clause could be ignored. After decades of First Nations resistance, in 1979, the government finally recognized its constitutional and treaty responsibilities for health care, which remains its Indian Health Policy.

Most Indian hospitals closed, and some were converted into primary care clinics. First Nations resistance was not intended to preserve the inadequate Indian hospitals, but to urge the government to acknowledge its treaty commitments and to help them address the health disparities that so many communities endured. Their resistance represented a broader effort at self-determination to address poverty, overcrowded housing, contaminated water, and inadequate infrastructure that gave rise to much illness in the first place.

Reconciliation

On 25 January 2018, former patients of Indian hospitals filed a $1.1-billion class-action lawsuit against the federal government. In January 2020, a judge certified the class-action lawsuit, allowing it to move forward. In 2025, the federal government and survivors of Indian hospitals represented in the class action lawsuit reached a settlement agreement. On 24 June 2025, the Federal Court accepted the settlement agreement. The settlement agreement offers individual compensation to survivors of Indian hospitals who suffered abuse. Additionally, it provides $150 million for a healing fund and an additional $235.5 million for education and research.

On 18 September 2024, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) formally apologized for the experiences of Indigenous peoples in Canada’s health systems. The CMA began their apology by acknowledging the specific harms done to Indigenous peoples in Indian hospitals and the ways in which the medical profession did not uphold its fundamental standards of practice. In the account of mistreatments, the CMA acknowledged medical experimentation that was done to Indigenous children and adults, which were present at Indian hospitals and in residential schools. The CMA also recognized ongoing harms faced by Indigenous peoples in the health system, including racism and discrimination. In the apology, the CMA stated,

To Indigenous Peoples living in Canada, we apologize to you. We are sorry. We are sorry we have lost your trust and for the harms you, your ancestors, your families and your communities have experienced. We acknowledge there are ripple effects on future generations. We take ownership of the CMA’s history, and we are committed to righting our wrongs and rebuilding our relationship on a foundation of trust, accountability and reciprocity.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom